Volume 354:601-609

Rebecca S. Gruchalla, M.D., Ph.D., and Munir Pirmohamed, Ph.D., F.R.C.P.

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the authors' clinical recommendations.

A 55-year-old woman presents to the hospital with cellulitis. She reports a history of urticaria 30 years earlier associatedwith taking penicillin for a respiratory tract infection. Should cephalosporins be avoided? More generally, how should patients with a history of allergy to antibiotics be evaluated and treated?

The Clinical Problem

Although allergic reactions to antibiotics account for only a small proportion of reported adverse drug reactions, they are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality and increased health care costs.1,2,3 Estimates of the prevalence of antibiotic allergy vary widely.1,2,3Any organ may be affected, but the skin is most commonly involved. Data from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program1indicate a 2.2 percent frequency of cutaneous drug reactions among hospitalized patients, with the antibiotics amoxicillin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and ampicillin the most commonly implicated agents. More recently, a six-month prospective analysis in France showed a prevalence of cutaneous drug eruptions of 3.6 per 1000 hospitalized patients; antibiotics accounted for 55 percent of cases.4

Pathogenetic Features

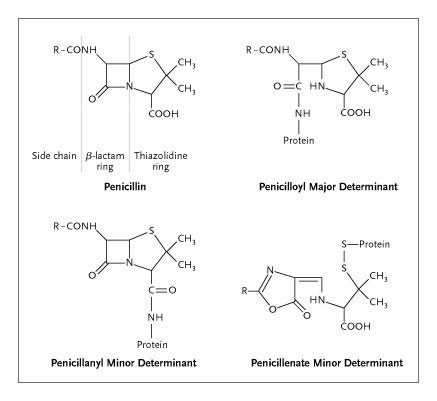

Allergic reactions are, by definition, immunologically mediated. A single drug may initiate multiple immune responses, and multiple antigenic determinants may be formed from a single drug.5,6 For instance, a major antigenic determinant and several minor determinants have been identified for penicillin (Figure 1).7 T cells play a predominant role in delayed hypersensitivity reactions, including antibiotic-induced maculopapular eruptions (Figure 2),8 whereas drug-specific IgE antibodies cause urticarial reactions (Figure 3). A classification of drug-induced immune responses is in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at www.nejm.org.

Figure 1. General Structure of Penicillin and Important Major and Minor Allergenic Determinants.

Figure 2. Maculopapular Rash Associated with Flucloxacillin Allergy.

Photograph courtesy of Peter Friedmann, University of Southampton, United Kingdom.

Figure 3. Urticaria Associated with Ampicillin Allergy.

Photograph courtesy of Peter Friedmann, University of Southampton, United Kingdom.

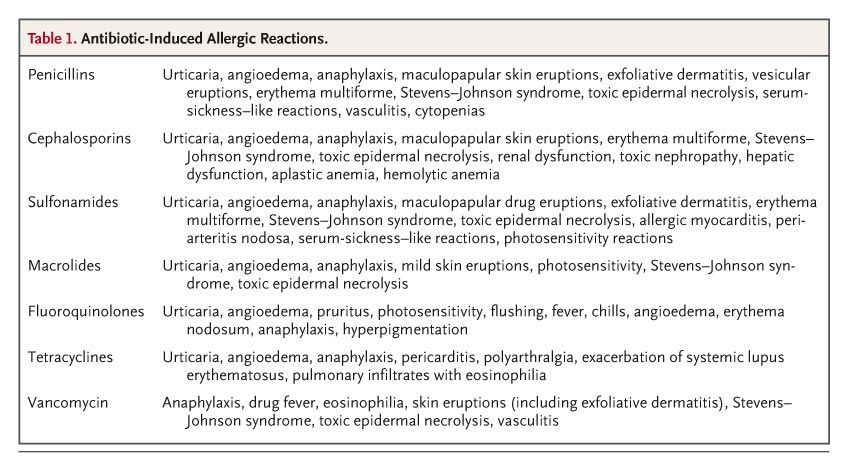

Clinical Features

The clinical features of antibiotic allergy are highly variable in terms of the type and severity of the reaction and the organ systems affected (Table 1). Factors such as the type of drug used, the nature of the disease being treated, and the immune status of the patient are all believed to play an important role in the clinical expression of these responses.9 The most common reactions to antibiotics are maculopapular skin eruptions, urticaria, and pruritus.1,10 These reactions typically occur days to weeks after initial exposure to a drug (during which sensitization occurs), although on secondary exposure, the reaction usually occurs much sooner, sometimes within minutes to hours.11 Occasionally, a hypersensitivity syndrome develops that is characterized by fever, eosinophilia, and other extracutaneous manifestations.12

Table 1. Antibiotic-Induced Allergic Reactions.

Some antibiotics also affect organs other than the skin. For instance, the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid can cause cholestatic liver injury, whereas hemolysis and cytopenias, most likely caused by drug-specific antibodies, are reported with high-dose penicillin and cephalosporin therapy.13 Severe reactions such as anaphylaxis, mediated by drug-specific IgE antibodies, are rare. Although anaphylaxis may theoretically occur with any antibiotic, only the frequency of penicillin-induced anaphylaxis is well described (1 in 5000 to 10,000 courses of drug therapy).14

Special Cases

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have a higher frequency of allergic reactions to a range of antimicrobial agents (including sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin, clindamycin, dapsone, and amithiozone) than do persons without HIV infection.15 Hypersensitivity to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazoleoccurs in 20 to 80 percent of patients infected with HIV, as compared with 1 to 3 percent of persons not infected with HIV.16 These high rates of reaction are not well understood but may be caused by altered drug metabolism, decreased glutathione levels, or both.15,17

Cystic Fibrosis

In approximately 30 percent of patients with cystic fibrosis, allergy develops to one or more antibiotics.18 Piperacillin, ceftazidime, and ticarcillin have been most commonly implicated, with the risk being higher after parenteral administration than after oral administration. Repeated exposure to antibiotics and immune hyperresponsiveness are thought to underlie the high prevalence of allergic reactions in patients with this disease.19

Infectious Mononucleosis

The likelihood of cutaneous reactions to penicillins and other antimicrobial agents is increased among patients with infectious mononucleosis.20,21 Although the mechanism of these drug reactions is not clear, the viral infection may alter the immune status of the host.22 In such cases, the implicated agent can be readministeredsafely once the viral infection has resolved.23

Strategies and Evidence

Clinical Assessment

Medical history taking is critical in the evaluation of antibiotic allergy24 and in distinguishing allergic reactions from other adverse reactions (Figure 4). This information is important, since overdiagnosis of allergic reactions can lead to unnecessary use of more costly antimicrobial agents and may promote the development of resistant microorganisms.15 Table 2 provides questions, the answers to which may help determine whether a reaction is immunologically mediated and, if so, the type ofimmune mechanism responsible. Whenever possible, patients who are being evaluated for possible antibiotic allergy should be encouraged to provide all medical records related to previous adverse drug reactions. Table 1 summarizes the most common reactions associated with various antibiotic classes.27

Figure 4. Algorithm for the Management of Antibiotic Allergy.

Nonimmune-mediated drug reactions are more common than are immune-mediated reactions. Treatment of immune-mediated reactions depends on whether the patient has a history of an immediate, IgE-mediated reaction (e.g., anaphylaxis), as compared with a delayed reaction that is mediated by T cells, antibodies, or immune complexes (categorized as type 2 to 4 hypersensitivity reactions). Skin testing is used for the detection of allergen-specific IgE antibodies. A negative response on a skin test cannot be interpreted to mean that IgE antibodies are absent except in the case of penicillin, in which case readministration of the drug in patients with a negative skin test is associated with a minimal risk of immediate reaction. Severe reactions include cytopenias, immune-complex disease, hypersensitivity syndrome, blistering rashes, and involvement of extracutaneous organs such as the liver. Treatment options are determined by the nature and severity of the reaction. In all cases, however, education and communication with the patient and the referring physician as to the detailed nature of the final diagnosis are vital to ensure the success of the management strategy and to prevent a recurrence of antibiotic allergy.

Table 2. Checklist for Distinguishing Immune-Mediated Reactions from Nonimmune-Mediated Reactions.

中間一部分內容我就省略了,有需要的人可以自己去官網查詢

Treatment

Drug Desensitization

For reactions that are presumed to be mediated by IgE, drug desensitization may be performed if the implicated agent is required for treatment.29 Desensitization is performed by a person with appropriate training, typically in a hospital setting. It involves the administration of increasing amounts of the antibiotic slowly over a period of hours until a therapeutic dose is reached. The typical starting dose is in micrograms; the route of administration may be oral or intravenous, but the oral route appears to be associated with fewer reactions. Doses are doubled every 15 to 30 minutes; therapeutic levels can be obtained in most cases within 4 to 5 hours.29,39 The patient is monitored closely throughout the procedure, and antihistamines and inhaled  -agonists are given for urticarial reactions and bronchospasm, respectively. If a mild reaction (e.g., flushing or urticaria) occurs, the procedure may resume at the last tolerated dose; if a reaction is severe (hypotension or severe bronchospasm), the procedure should be aborted and an alternative antibiotic selected.

-agonists are given for urticarial reactions and bronchospasm, respectively. If a mild reaction (e.g., flushing or urticaria) occurs, the procedure may resume at the last tolerated dose; if a reaction is severe (hypotension or severe bronchospasm), the procedure should be aborted and an alternative antibiotic selected.

The mechanism by which clinical tolerance is achieved is unclear, but it is thought to involve antigen-specific mast-cell desensitization.40 Since maintenance of a desensitized state requires the continuous presence of the drug, desensitization must be repeated if the antibiotic is required again later.

In a recent retrospective report,41 desensitization for IgE-mediated drug allergy was successful in 43 of 57 cases (75 percent). Eleven desensitizations (19 percent) were complicated by severe allergic reactions, either during the procedure (anaphylaxis) or days after its completion (serum sickness); three were terminated for reasons other than allergic reactions. In most cases of failed desensitization, the drug reaction did not appear to be solely mediated by IgE. Desensitization appears more likely to fail in patients with cystic fibrosis.19,41

Graded Challenge

For reactions that are not considered to be mediated by IgE, management depends on the clinical manifestations of the previous reaction. For maculopapular eruptions, the specialist may consider a graded drug challenge, which is equivalent to provocation testing.29 Initial starting doses are generally higher than those used for desensitization (milligrams vs. micrograms), and the interval between doses varies, ranging from hours to days or even weeks. The patient is monitored for adverse reactions, which are most commonly cutaneous. The decision whether to discontinue an antibiotic if a reaction occurs depends on the nature of the reaction; bullous lesions or those involving mucous membranes warrant withdrawal of the drug, whereas it may be reasonable to treat through milder reactions, such as maculopapular eruptions, with the use of antihistamines, corticosteroids, or both as needed.

During drug readministration, repeated hypersensitivity reactions (morbilliform eruptions, fever, or both) have been noted in 58 percent of patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome who have had previous reactions to sulfamethoxazole.42 Several graded-challenge procedures have been used successfully in suchpatients. An analysis of several studies showed that readministration of sulfamethoxazole with the use of an incremental-dosing regimen permitted the use of the drug in more than 75 percent of treated patients.43 Repeated administration is contraindicated, however, after any life-threatening reaction that is not mediated by IgE (e.g., drug-induced hemolytic anemia, immune-complex reactions, the Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis).

Cephalosporin in Patients with Penicillin Allergy

Penicillins and cephalosporins share a ß-lactam ring structure, making cross-reactivity a concern. Although a rate of cross-reactivity of more than 10 percent has been reported, this figure must be interpreted with caution since it is based on retrospective studies in which penicillin allergy was not routinely confirmed by skin testing, and at least some of the reactions were probably not immune-mediated.44 Available data, although based on small numbers, suggest an increased risk of cephalosporin reactions among patients with positive results on penicillin skin tests. In a review combining data from 11 studies of cephalosporin administration in patients with a history of penicillin allergy,45 cephalosporin reactions were found to have occurred in 6 of 135 patients with positive skin-test results for penicillinallergy (4.4 percent), as compared with only 2 of 351 with negative skin tests (0.6 percent).

Whereas most patients who have a history of penicillin allergy will tolerate cephalosporins, indiscriminate administration cannot be recommended, especially for patients who have had life-threatening reactions.29 Among 12 cases of fatal anaphylaxis caused by antibiotics in the United Kingdom from 1992 to 1997, 6 cases occurred after the first dose of a cephalosporin, and 3 of the 6 patients were known to have penicillin allergy.46

For patients with a history of penicillin allergy who require a cephalosporin, treatment depends on whether the previous reaction was mediated by IgE.29,47 Skin testing is warranted if the reaction was consistent with an IgE-mediated mechanism or if the history is unclear. In one study, one third of patients with positive results on skin tests had unclear or vague histories of penicillin allergy.48 If testing is positive and a cephalosporin is considered necessary, then desensitization should be performed with the use of the particular cephalosporin chosen for treatment. A possible alternative is to perform a graded challenge with the cephalosporin,29 but the risk of anaphylaxis, although low, must be recognized.29 If the history is inconsistent with an IgE-mediated mechanism, it is considered safe to initiate a graded challenge without previous skin testing.

Sulfonamide Allergy

For patients who have a history of allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, concern has been raised about the use of other sulfonamide-containing drugs (diuretics, sulfonylureas, and celecoxib). However, sulfonamide antimicrobial agents (sulfamethoxazole, sulfadiazine, sulfisoxazole, and sulfacetamide) differ from other sulfonamide-containing medications by having an aromatic amine group at the N4 position and a substituted ring at the N1 position; these groups are not found in nonantibiotic sulfonamide-containing drugs. Thus, despite product-labeling warnings, cross-reactivity between these two groups of sulfonamides is believed to be unlikely.49,50

In a large observational study,51 patients with a history of allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics had an increased risk of an allergic reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides, as compared with patients without such a history (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; 95 percent confidence interval, 2.1 to 3.7), and were even more likely to have a reaction to penicillin (adjusted odds ratio, 3.9; 95 percent confidence interval, 3.5 to 4.3). These results suggest that the association between an allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics and subsequent reactions to nonantibiotic sulfonamide drugs is probably attributable to a predisposition to allergic reactions in general, as opposed to cross-reactivity between sulfonamide-containing antibiotics and nonantibiotic drugs.51 However, the results must be interpreted with caution, given the retrospective design and the use of diagnosis codes to categorize reactions, which probably resulted in some misclassification of nonallergic reactions as allergic reactions.

Areas of Uncertainty

The mechanisms underlying antibiotic allergy have not been clearly elucidated. This understanding is needed to facilitate the development of better diagnostic tools and drugs that are less immunogenic. Better understanding is needed of factors mediating individual susceptibility to allergic reactions to antibiotics. A few studies have evaluated the role of major-histocompatibility-complex polymorphisms in the predisposition of patients to drug reactions,52,53 but these findings need to be confirmed and expanded.

Some patients have reported adverse reactions to many chemically unrelated antibiotics. The existence of the so-called multiple drug allergy syndrome is controversial,54,55 and accepted diagnostic tests are needed to document drug allergy in these patients.

Guidelines

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, and the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters for Allergy and Immunology have developed practice guidelines for the management of drug allergy29,47 on the basis of evidence and expert opinion. Therecommendations in the present review are consistent with these guidelines.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Patients who report a history of antibiotic allergy require a careful assessment of the nature of the reaction to determine the likelihood that it was immunologically mediated. For patients whose history suggests an IgE-mediated reaction to penicillin, such as the case described in the vignette, skin testing is indicated, if available, before they receive another ß-lactam antibiotic. If test results are negative, the ß-lactam agent may be administered. If test results are positive or testing cannot be done, the drug should be avoided or a desensitization procedure should be performed.

Source Information

From the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas (R.S.G.); and the Department of Pharmacology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom (M.P.).

Address reprint requests to Dr. Gruchalla at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390-8859, or at rebecca.gruchalla@utsouthwestern.edu.

References

- Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, Arndt K. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions: a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program on 15,438 consecutive inpatients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA 1986;256:3358-3363. [Free Full Text]

- Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998;279:1200-1205. [Free Full Text]

- Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15-19. [Free Full Text]

- Fiszenson-Albala F, Auzerie V, Mahe E, et al. A 6-month prospective survey of cutaneous drug reactions in a hospital setting. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:1018-1022. [CrossRef][Medline]

- Park BK, Pirmohamed M, Kitteringham NR. Role of drug disposition in drug hypersensitivity: a chemical, molecular, and clinical perspective. Chem Res Toxicol 1998;11:969-988. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Schnyder B, Mauri-Hellweg D, Zanni M, Bettens F, Pichler WJ. Direct, MHC-dependent presentation of the drug sulfamethoxazole to human alpha/beta T cell clones. J Clin Invest 1997;100:136-141. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Weltzien HU, Padovan E. Molecular features of penicillin allergy. J Invest Dermatol 1998;110:203-206. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Pichler WJ. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:683-693. [Free Full Text]

- Adkinson NF Jr. Drug allergy. In: Adkinson NF Jr, Yunginger J, Busse W, Bochner B, Holgate S, Simons F, eds. Middleton's allergy: principles and practice. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003:1679-94.

- Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2819-2822. [Free Full Text]

- Pirmohamed M, Breckenridge AM, Kitteringham NR, Park BK. Adverse drug reactions. BMJ 1998;316:1295-1298. [Free Full Text]

- Sullivan JR, Shear NH. The drug hypersensitivity syndrome: what is the pathogenesis? Arch Dermatol 2001;137:357-364. [Free Full Text]

- Pirmohamed M, Kitteringham NR, Park BK. The role of active metabolites in drug toxicity. Drug Saf 1994;11:114-144. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Rudolph AH, Price EV. Penicillin reactions among patients in venereal disease clinics: a national survey. JAMA 1973;223:499-501. [Free Full Text]

- Pirmohamed M, Park BK. HIV and drug allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;1:311-316. [Medline]

- van der Ven AJAM, Koopmans PP, Vree TB, van der Meer JW. Adverse reactions to co-trimoxazole in HIV infection. Lancet 1991;338:431-433. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Farrell J, Naisbitt DJ, Drummond NS, et al. Characterization of sulfamethoxazole and sulfamethoxazole metabolite-specific T-cell responses in animals and humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;306:229-237. [Free Full Text]

- Wills R, Henry RL, Francis JL. Antibiotic hypersensitivity reactions in cystic fibrosis. J Paediatr Child Health 1998;34:325-329. [Medline]

- Burrows JA, Toon M, Bell SC. Antibiotic desensitization in adults with cystic fibrosis. Respirology 2003;8:359-364. [CrossRef][Medline]

- Andersen Lund B, Bergan T. Temporary skin reactions to penicillins during the acute stage of infectious mononucleosis. Scand J Infect Dis 1975;7:21-28. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Pullen H, Wright N, Murdoch JM. Hypersensitivity reactions to antibacterial drugs in infectious mononucleosis. Lancet 1967;2:1176-1178. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Levy M. Role of viral infections in the induction of adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf 1997;16:1-8. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Nazareth I, Mortimer P, McKendrick GD. Ampicillin sensitivity in infectious mononucleosis -- temporary or permanent? Scand J Infect Dis 1972;4:229-230. [Medline]

- Gruchalla RS. Clinical assessment of drug-induced disease. Lancet 2000;356:1505-1511. [Erratum, Lancet 2001;357:724.] [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Mori K, Maru C, Takasuna K. Characterization of histamine release induced by fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents in vivo and in vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol 2000;52:577-584. [Medline]

- Veien M, Szlam F, Holden JT, Yamaguchi K, Denson DD, Levy JH. Mechanisms of nonimmunological histamine and tryptase release from human cutaneous mast cells. Anesthesiology 2000;92:1074-1081. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Litt JZ. Litt's drug eruption reference manual: including drug interactions. 10th ed. London: Taylor & Francis, 2004.

- Empedrad R, Darter AL, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Nonirritating intradermal skin test concentrations for commonly prescribed antibiotics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:629-630. [Medline]

- Bernstein I, Gruchalla RS, Lee R, Nicklas R, Dykewicz M. Executive summary of disease management of drug hypersensitivity: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999;83:665-700. [Medline]

- Gadde J, Spence M, Wheeler B, Adkinson NF Jr. Clinical experience with penicillin skin testing in a large inner-city STD clinic. JAMA 1993;270:2456-2463. [Free Full Text]

- Mendelson LM, Ressler C, Rosen JP, Selcow JE. Routine elective penicillin allergy skin testing in children and adolescents: study of sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1984;73:76-81. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Sogn DD, Evans R III, Shepherd GM, et al. Results of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Clinical Trial to test the predictive value of skin testing with major and minor penicillin derivatives in hospitalized adults. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:1025-1032. [Free Full Text]

- Lin RY. A perspective on penicillin allergy. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:930-937. [Free Full Text]

- Macy E, Mangat R, Burchette RJ. Penicillin skin testing in advance of need: multiyear follow-up in 568 test result-negative subjects exposed to oral penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:1111-1115. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Malakar S, Dhar S, Shah Malakar R. Is serum sickness an uncommon adverse effect of minocycline treatment? Arch Dermatol 2001;137:100-101. [Free Full Text]

- Ordoqui E, Zubeldia J, Aranzabal A, et al. Serum tryptase levels in adverse drug reactions. Allergy 1997;52:1102-1105. [Medline]

- Pichler WJ, Tilch J. The lymphocyte transformation test in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy 2004;59:809-820. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Messaad D, Sahla H, Benahmed S, Godard P, Bousquet J, Demoly P. Drug provocation tests in patients with a history suggesting an immediate drug hypersensitivity reaction. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:1001-1006. [Free Full Text]

- Solensky R. Drug desensitization. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2004;24:425-443. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Naclerio R, Mizrahi E, Adkinson NF Jr. Immunologic observations during desensitization and maintenance of clinical tolerance to penicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1983;71:294-301. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Turvey SE, Cronin B, Arnold AD, Dioun AF. Antibiotic desensitization for the allergic patient: 5 years of experience and practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004;92:426-432. [Medline]

- Carr A, Penny R, Cooper DA. Efficacy and safety of rechallenge with low-dose trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole in previously hypersensitive HIV-infected patients. AIDS 1993;7:65-71. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Rich JD, Sullivan T, Greineder D, Kazanjian PH. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole incremental dose regimen in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1997;79:409-414. [Medline]

- Saxon A, Beall GN, Rohr AS, Adelman DC. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:204-215.

- Kelkar PS, Li JT. Cephalosporin allergy. N Engl J Med 2001;345:804-809. [Free Full Text]

- Pumphrey RS, Davis S. Under-reporting of antibiotic anaphylaxis may put patients at risk. Lancet 1999;353:1157-1158. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Lieberman P, Kemp S, Oppenheimer J, Lang D, Bernstein I, Nicklas R. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115:Suppl:S483-S523. [CrossRef][Medline]

- Solensky R, Earl HS, Gruchalla RS. Penicillin allergy: prevalence of vague history in skin test-positive patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2000;85:195-199. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Brackett CC, Singh H, Block JH. Likelihood and mechanisms of cross-allergenicity between sulfonamide antibiotics and other drugs containing a sulfonamide functional group. Pharmacotherapy 2004;24:856-870. [Medline]

- Knowles S, Shapiro L, Shear NH. Should celecoxib be contraindicated in patients who are allergic to sulfonamides? Revisiting the meaning of `sulfa' allergy. Drug Saf 2001;24:239-247. [CrossRef][Web of Science][Medline]

- Strom B, Schinnar R, Apter A, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1628-1635. [Free Full Text]

- O'Donohue J, Oien KA, Donaldson P, et al. Co-amoxiclav jaundice: clinical and histological features and HLA class II association. Gut 2000;47:717-720. [Free Full Text]

- Romano A, De Santis A, Romito A, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity to aminopenicillins is related to major histocompatibility complex genes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998;80:433-437. [Web of Science][Medline]

- Macy E. Multiple antibiotic allergy syndrome. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2004;24:533-543. [CrossRef][Medline]

- Warrington R. Multiple drug allergy syndrome. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2000;7:18-19. [Medline]

最後,補上一則說明:

To the Editor: Gruchalla and Pirmohamed (Feb. 9 issue)1 recommend that before the initiation of cephalosporin therapy, skin testing should be performed for patients with a suspected history of IgE-mediated reactions to penicillins. We would like to add that it is equally important to recognize the potential for cross-reactivity between penicillins and carbapenems. From our experience, this relationship is often not recognized among clinicians. With the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria with extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, the use of carbapenems has somewhat expanded beyond the traditional use in only the sickest of patients.

The authors adroitly state that the rate of cross-reactivity of "more than 10 percent" between penicillins and cephalosporins has not been well established. Concerning cross-reactivity between penicillins and carbapenems, three retrospective clinical studies reported rates of reaction to carbapenems of 9 to 11 percent among inpatients with a reported penicillin allergy.2,3,4 An earlier study reported that of 20 subjects with a positive penicillin skin test, 10 reacted to an imipenem reagent.5 We would recommend that in patients with a history of penicillin allergy, the same concerns and caveats apply to both the cephalosporins and carbapenems.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢