BACKGROUND

Treatment of

latent tuberculosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) is efficacious, but few patients around the world receive such treatment.

We evaluated three new regimens for latent tuberculosis that may be more potent

and durable than standard isoniazid treatment.

METHODS

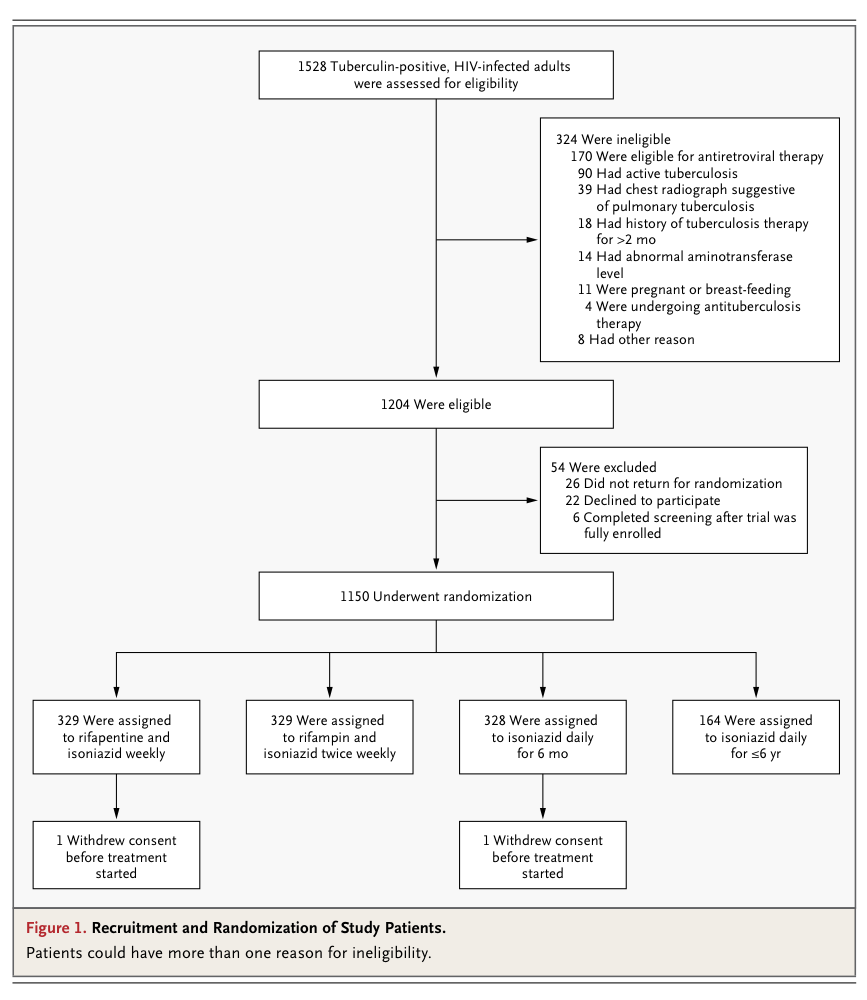

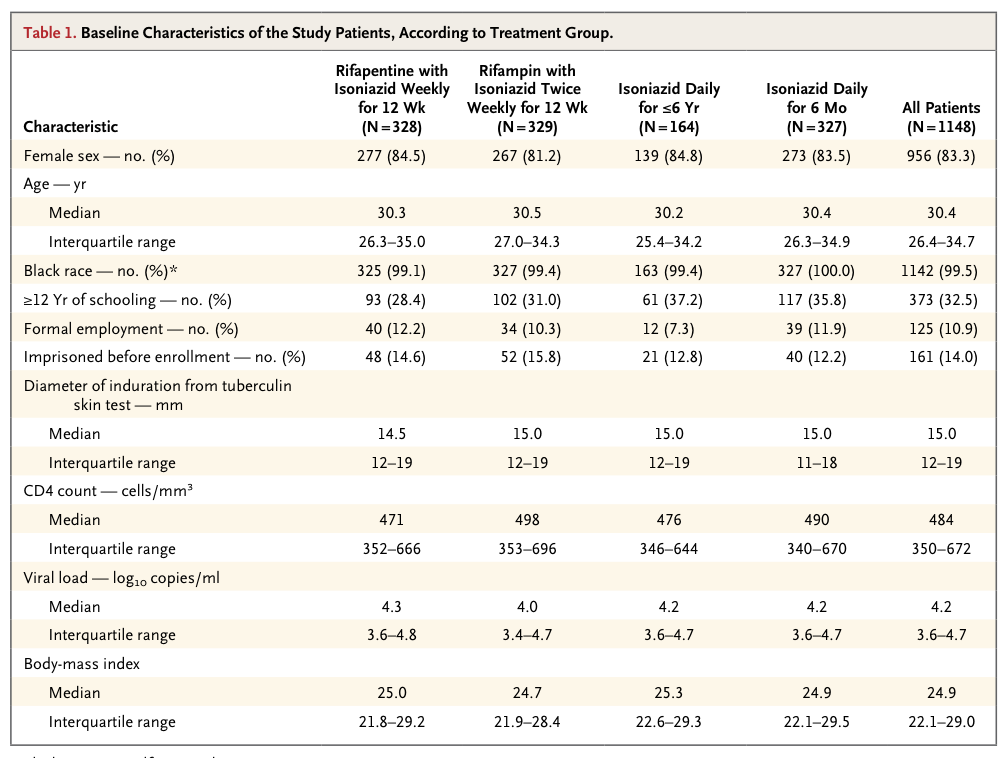

We randomly assigned South African adults with HIV infection and a positive tuberculin skin test who were not taking antiretroviral therapy to receive rifapentine (900 mg) plus isoniazid (900 mg) weekly for 12 weeks, rifampin (600 mg) plus isoniazid (900 mg) twice weekly for 12 weeks, isoniazid (300 mg) daily for up to 6 years (continuous isoniazid), or isoniazid (300 mg) daily for 6 months (control group). The primary end point was tuberculosis-free survival.

RESULTS

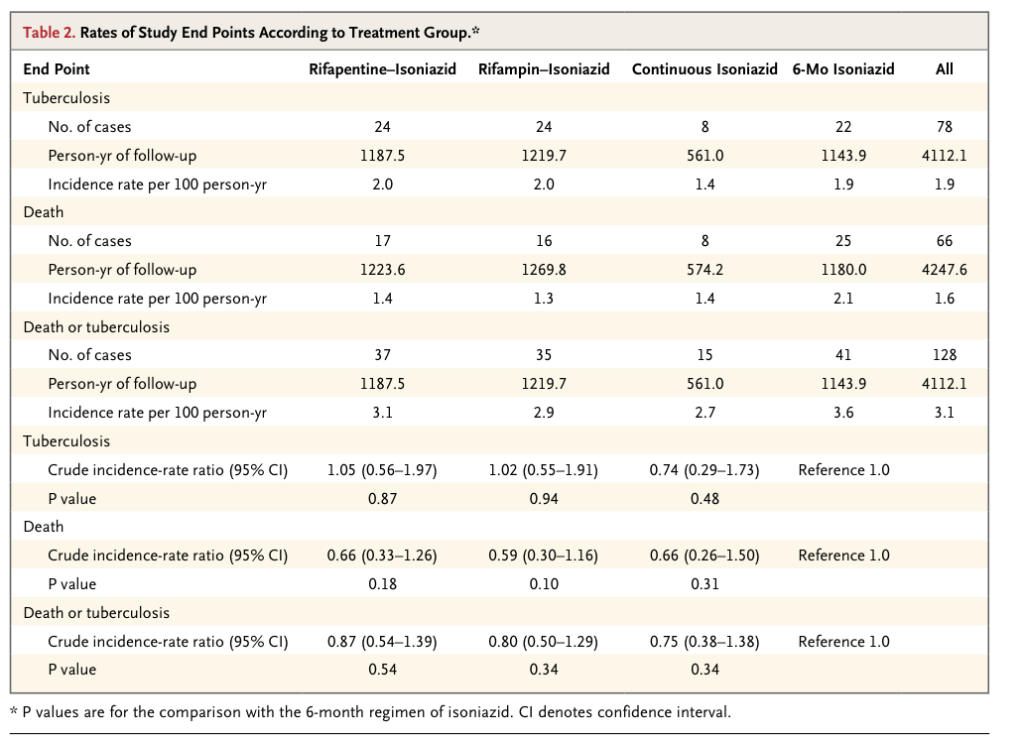

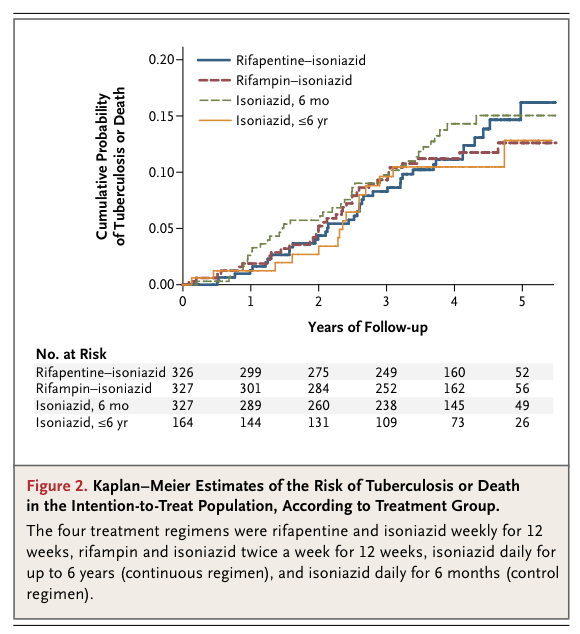

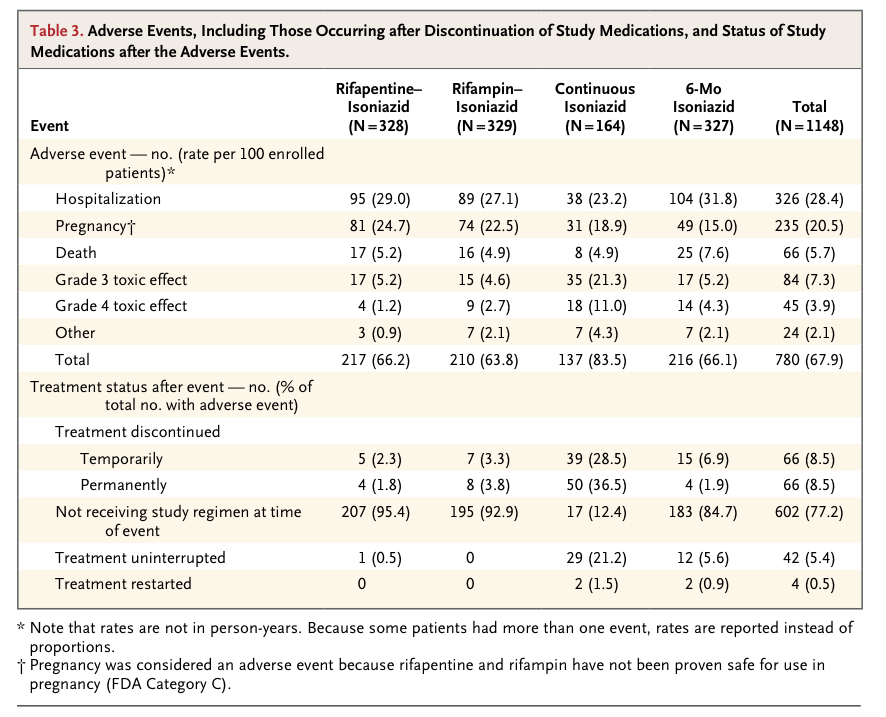

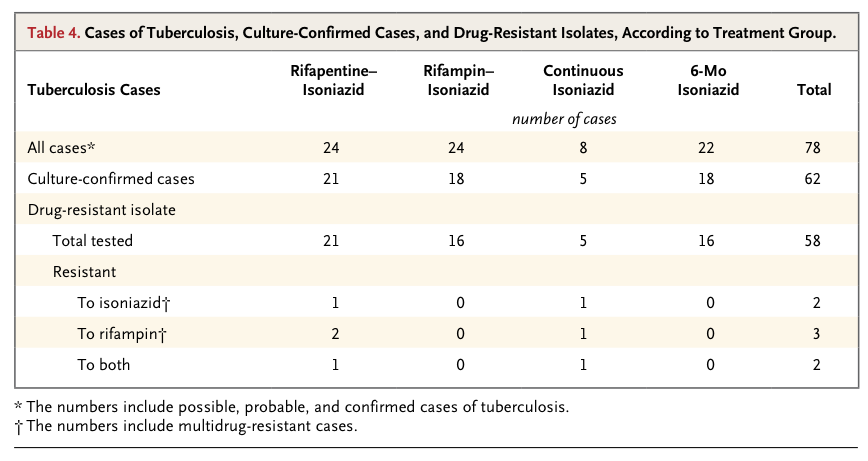

The 1148 patients had a median age of 30 years and a median CD4 cell count of 484 per cubic millimeter. Incidence rates of active tuberculosis or death were 3.1 per 100 person-years in the rifapentine–isoniazid group, 2.9 per 100 person-years in the rifampin–isoniazid group, and 2.7 per 100 person-years in the continuous-isoniazid group, as compared with 3.6 per 100 person-years in the control group (P>0.05 for all comparisons). Serious adverse reactions were more common in the continuous-isoniazid group (18.4 per 100 person-years) than in the other treatment groups (8.7 to 15.4 per 100 person-years). Two of 58 isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3.4%) were found to have multidrug resistance.

DISCUSSION

We found that three new prophylactic regimens against tuberculosis in HIV-infected adults were not superior to the control regimen of isoniazid therapy for 6 months. The overall rate of tuberculosis was 1.9 cases per 100 person-years, with no significant difference between any of the three new regimens and the control regimen. Among HIV-infected people in Africa with a positive tuberculin skin test who are not receiving antituberculosis treatment, the expected annual rate of tuberculosis ranges from 5 and 10%.2,4,6,7 The rate of tuberculosis in the control group was also substantially lower than anticipated, suggesting that all the treatments used in this study performed better than regimens used in earlier African studies.10,11 The shorter, rifamycin-based regimens had higher adherence rates than did the 6-month isoniazid regimen and did not appear to select for drug-resistant M. tuberculosis in the small number of isolates cultured. These results are consistent with an earlier study showing the efficacy of daily isoniazid and rifampin in adults with HIV infection,2 but we found that a twice-weekly regimen was also efficacious.

No clinically significant safety concerns were identified with the once-weekly regimen of rifapentine and isoniazid in our study, a finding that is similar to the results of a smaller trial involving household contacts of patients with tuberculosis in Brazil.14 A recent, large trial of this regimen as compared with 9 months of isoniazid in a population largely uninfected with HIV showed noninferiority, which is consistent with our results.20 The use of intermittent, short-course rifamycin regimens to prevent tuberculosis is appealing because adherence is improved, therapy can be supervised, and adverse reactions should be minimized. Use of rifamycins is problematic in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors, which are metabolized by P-450 cytochromes, but concomitant use of rifampin and efavirenz does not appear to compromise antiviral activity.21

We found no additional benefit of continuous isoniazid as compared with 6 months of isoniazid as preventive treatment in our intention-to-treat analysis. Our study was not blinded, however, and patients assigned to continuous isoniazid discontinued treatment for a number of reasons. Our post hoc analyses suggest that continuous isoniazid was effective while patients were taking the drug but that its effectiveness was lost when treatment ended. Hepatotoxic adverse events were more common with continuous isoniazid than with the 6-month regimen, but none of these events were fatal. Our results support data from a trial in Botswana comparing a 3-year course of isoniazid therapy with the 6-month regimen, in which the longer regimen was superior.22 The Botswana trial was placebo-controlled, and the rate of treatment discontinuation with prolonged isoniazid treatment was lower in that study than in ours. Taken together, these data suggest that longer courses of isoniazid are efficacious but that the benefit will be compromised by discontinuation of treatment and adverse events.

Adherence to antituberculosis therapy was good in our trial, a finding that is consistent with reports from African programs showing that 70 to 90% of HIV-infected adults given isoniazid completed treatment.23,24 In our trial, adherence to the three shorter regimens was better than adherence to continuous isoniazid.

Intermittent rifapentine therapy for active tuberculosis in patients with advanced HIV infection has been associated with the emergence of organisms that are resistant to rifampin.25 Overall, the prevalence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in our study was 3.4%, which is similar to estimates in South Africa at the time of our study.26 We did not detect increased selection of resistant organisms, probably because of the reduced bacterial load in latent tuberculosis; however, our sample was small.

The prevalence of active tuberculosis was 5.9% among the adults screened for this trial, which is similar to the prevalence among HIV-infected patients in South Africa and other areas with a high burden of tuberculosis when they begin to receive antiretroviral therapy27,28 or prenatal care.29 The World Health Organization has recently revised its guidelines for antituberculosis therapy30 to recommend the use of isoniazid for all HIV-infected persons at high risk for tuberculosis, including pregnant women, children, and patients receiving antiretroviral therapy, regardless of tuberculin status. We studied only HIV-infected adults with a positive tuberculin skin test, who account for up to 50% of HIV-infected patients in southern Africa and make up a group at particularly high risk for the development of tuberculosis; thus, our results may not be generalizable to lower-risk groups.

In summary, short-course, rifamycin-based preventive treatment had similar, not superior, efficacy to 6 months of isoniazid in tuberculin-positive adults infected with HIV. Use of these regimens in clinical practice could substantially increase the number of patients who receive and complete preventive therapy. Our findings, along with those of other investigators,22 suggest that continuous treatment with isoniazid may be effective in preventing reactivation of and reinfection with M. tuberculosis in Africa. More widespread use of preventive therapy, regardless of the regimen chosen, is essential to help control the epidemic of HIV-related tuberculosis.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢