INTRODUCTION

There is increasing recognition of the similarities in the etiology of constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) and chronic constipation (CC), and a more inclusive terminology is emerging of constipation-related functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, which embraces both conditions. This is partly driven by the increasing appreciation that IBS-C and CC share a number of common underlying causes and presenting symptoms, which are described below.

However, the vast majority of published literature treats IBS-C and CC as separate entities, and therefore, this article will integrate the pathophysiology of IBS-C and CC, but in the light of the available data, these conditions will then be discussed individually.

In the final section a case scenario is provided, which aims to bring together some of the emerging considerations about integrating the management of IBS-C and CC.

In IBS-C and CC, a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms have been reported, and there is considerable overlap in the symptoms for which a number of common pathophysiologic mechanisms have been proposed. This section highlights the similarities and differences in the possible etiologies of IBS-C and CC.

Shared factors include decreased bowel motility, pelvic floor dysfunction, visceral hypersensitivity, psychological stressors, altered bowel flora, and diet. There has been a long-standing belief that altered GI motor function exists in some cases of IBS-C and CC, specifically decreased motility and delayed bowel transit. Studies have shown decreased rectal, colonic, and small bowel motility in IBS-C (Quigley, 2005). These abnormalities are best exemplified in the subset of CC known as colonic inertia, a condition defined by a slow colon transit time (Stivland et al, 1991). Pelvic floor dysfunction or dyssynergic defecation is characterized by the inability to coordinate the sequence of events that result in normal evacuation of stool. This includes some combination of the inability to contract the abdominal wall musculature, deficient relaxation of the puborectalis muscle, impaired rectal contraction, paradoxical anal contraction, and/or inadequate anal relaxation (Rao et al, 1998). Although recently identified as a contributor to symptoms in a subset of IBS-C (Prott et al, 2010), this mechanism has also been recognized as a primary etiology of symptoms in a subset of patients with CC (Lembo, Camilleri, 2003).

Visceral hypersensitivity, reflecting a lower pain threshold for the digestive tract, is not only a well-defined pathophysiologic mechanism underlying IBS-C, but also suggested by some to be a biomarker of the condition (Mertz et al, 1995; Bouin et al, 2002; Lawal, 2006). Visceral hypersensitivity results from altered interactions between the central nervous system and enteric nervous system, commonly known as the brain-gut axis (Drossman, 1999). The nociceptive pathways that may be involved in the brain-gut axis have provided, and continue to provide, potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of IBS-C. On the other hand, according to the Rome III definition, abdominal pain plays a much smaller role in CC, as does visceral hypersensitivity (Longstreth et al, 2006a). Psychological stress may be responsible for symptom development in IBS (O'Malley et al, 2011) and may worsen symptoms. In contrast, psychological stress appears to play a smaller role in CC, but is believed to promote dyssynergic defecation in some cases (Rao, 2007).

There is emerging evidence to suggest a role for altered bowel flora in the development of symptoms in IBS-C, and possibly CC (Attaluri et al, 2010). A long-held connection between low-fiber diet and CC is better defined in CC than for IBS-C (Trowell, 1976).

It is important to understand that none of these individual pathophysiologic mechanisms are universally reported in either IBS-C or CC. More often than not, it is a combination of 2 or more of these etiologic factors that are responsible for symptoms of IBS-C and CC.

PART 1: IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME WITH PREDOMINANT CONSTIPATION

IBS Subgroups

IBS is a common GI functional disorder, characterized by symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort directly associated with disturbances in defecation that are not explained by identifiable structural or biochemical abnormalities (Drossman et al, 2002; Longstreth et al, 2006b). Patients with IBS are subtyped based on bowel symptoms into those with predominant constipation (IBS-C) predominant diarrhea (IBC-D), or a mixture of both symptoms (IBS-M) (Longstreth, 2005; Thompson WG, 1993; Longstreth et al, 2006a). The definition of IBS has evolved over time, now relying upon the use of symptom-based criteria, such as Rome III and the judicious use of selected diagnostic testing to exclude organic disease (Longstreth et al, 2006a; Furman, Cash , 2011).

One systematic review reported that population-based studies from the US (based on Manning criteria) found similar distributions between IBS-C, IBS-D and mixed IBS (IBS-M) (Guilera et al, 2005). However, based on a survey of 249 IBS patients, 18% of patients with IBS had constipation-predominant symptoms, 36% had diarrhea-predominant symptoms and 46% have a mixed pattern of symptoms (Ersryd et al, 2007). Potential explanations for the variance between publications include differences in geography, gender, demographics, and criteria applied to the populations studied.

Unfortunately, much of the literature concerning IBS epidemiology does not differentiate the study populations into these specific sub-types, and addresses the condition as a whole. Where possible, this article will draw these subgroup distinctions and will focus specifically on data relating to IBS-C.

Epidemiology and Demographics

The prevalence of IBS depends on the diagnostic criteria used and the characteristics of the population studied (primary care vs specialty clinic). In a comprehensive review of IBS epidemiology in North America in 2002, prior to Rome II, the prevalence estimates ranged from 3% to 20% (Saito et al, 2002). In a more recent study in the United States and Canada, using Rome II criteria, the IBS prevalence was reported as 5% to 12%, according to age (Talley et al, 1992a). Finally, based on Rome III, the prevalence of IBS has been estimated to range from 10% to 18% in the general population of Western countries (Jung et al, 2007; Olafsdottir et al, 2010).

In Western studies there is a predominance of females with IBS (pooled odds ratio [OR] 1.46; (% CI 1.13‒1.88) (Andrews et al, 2005; Hungin et al, 2005; Minocha et al, 2006; Saito et al, 2002). However, across Asia, a female predominance has not been consistently reported. Generally, younger persons are more likely to be affected with IBS. However, patients of all ages can suffer with this condition. For example, Talley et al showed that the prevalence of IBS increases with age from 8% among those aged 65 to 74 years to more than 12% for those older than 85 years of age (Talley et al, 1992a). Several studies have shown an inverse relationship between IBS prevalence and annual income (Andrews et al, 2005; Minocha et al, 2006; Saito et al, 2002; Hungin et al, 2005).

The prevalence of IBS is generally similar in white and black populations, although some data have suggested it may be lower in Hispanics than in non-Hispanic whites in the United States (Talley, 2010).

IBS is the digestive disorder most often diagnosed by gastroenterologists, accounting for 28% of all patients, and between 30% and 50% of referrals to gastroenterologists. IBS also accounts for 12% of diagnoses made by primary care physicians. (Drossman et al, 2002). Indeed, the National Diseases and Therapeutic Index (NDTI) shows that the condition accounts for 2.6 million office-based visits and 3.5 million all-location visits (Sandler 1990). However, despite this large number, only a limited proportion of sufferers seek medical attention, and the actual number of patients with IBS is probably larger than that reported (Drossman et al, 2002).

IBS is a chronic disorder that may wax and wane for years. In a 1-year study in which Talley et al surveyed a population twice over a 12- to 20-month period, the prevalence of IBS was similar on both occasions (Talley et al, 1992b). However, about 9% of people with symptoms on the first survey did not have symptoms on the second survey, and about 38% of those with IBS reported that their symptoms had disappeared during the period between the 2 surveys. In a systematic review of the natural history of physician-diagnosed IBS, ~30% to ~50% of patients had unchanged symptoms with longitudinal follow-up (El-Serag et al, 2004). These data suggest that IBS is a chronic condition with symptoms relatively stable over time in up to half the patients. However, a significant proportion of IBS patients will experience a more dynamic clinical course with resolution or a change in their symptoms when followed over prolonged periods of time.

IBS is not associated with an increase in mortality. In a recent study from Olmsted County, which involved 4,176 respondents from randomly selected residents, there was no association between survival and IBS detected in more than 30,000 person-years of follow-up (Chang et al, 2010).

IBS can affect patients physically, psychologically, socially, and economically, and in the past 2 decades, the condition has gained considerable attention in the healthcare field due to its high prevalence (Longstreth et al, 2006a).

Typically, IBS symptoms are chronic and episodic, causing debilitating symptoms over years. This is illustrated in a survey of 1597 patients with IBS; 50% said that they had experienced symptoms for > 10 years, 57% experienced symptoms daily, 25% weekly and 14% monthly. Moreover, only 4% of patients rated their symptoms as mild. This is in line with the results of a survey conducted by the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD) in 2002, when 39% of respondents rated their IBS symptoms as extremely or very severe (Hulisz, 2004).

Studies have shown that the duration of symptom flares and the presence of abdominal pain (as opposed to abdominal discomfort) is associated with an impact on the physical component of HRQOL in IBS (Spiegel et al, 2004b). Mental symptoms are associated with abnormalities in sexuality, mood, and anxiety (Spiegel et al, 2004b). These symptoms are associated with feelings of chronic stress, exhaustion, and sleep difficulties and also have an impact on social integration and activities (Spiegel et al, 2004b). Moreover, data consistently show that patients with IBS score lower on all 8 domains of the SF-36 HRQOL questionnaire, compared with a normal non-IBS cohort. Indeed, IBS patients have a similar physical HRQOL as patients with diabetes and a lower score than patients with depression or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Also, the mental SF-36 scores were lower in patients with IBS than those with chronic renal failure and similar to Class 3 congestive heart failure (CHF) and rheumatoid arthritis (Spiegel, 2009b). IBS unquestionably has a negative impact on HRQOL, and failing to recognize this could undermine the physician-patient relationship and lead to dissatisfaction with care. These findings suggest that in addition to the physical criteria used to judge IBS HRQOL (eg, stool frequency, stool characteristics), global symptom severity should also be addressed, including psychological status and symptom-related fears that might contribute to the low HRQOL score (Agarwal et al, 2011).

Administering a full HRQOL instrument is not likely to be practical in the busy clinic setting. To assist with this, a short questionnaire has been developed specifically for use in everyday clinical practice. Administered in the waiting room, a nurse can quickly score the results and provide this to the doctor ahead of the consultation. This questionnaire is called the BEST score because the 4 questions spell out BEST (Speigel et al, 2006):

- How Bad are your bowel symptoms?

- Can you still Enjoy the things you used to enjoy?

- Do you feel like your bowel symptoms mean there's something Seriously wrong?

- Do your bowel symptoms make you feel Tense?

It is important that healthcare professionals (HCPs) are aware of the negative impact of IBS on patients; if their symptoms are not satisfactorily controlled, they tend to visit their doctors more, consume more diagnostic resources, take more medications, miss more workdays, and have a lower work productivity. Moreover, they are hospitalized more frequently and consume more direct costs than those without IBS. Resource utilization is highest in patients with severe symptoms and poor HRQOL (Spiegel et al, 2009b).

The annual costs of IBS treatment in the United States has been estimated to be over $20 billion in both direct ($1.6 billion) and indirect ($19.2 billion) expenditures (Shih et al. 2002), which is staggering considering the proportion of those with IBS who do not seek medical attention (Talley et al, 1997). This is driven by the associated absenteeism, more frequent healthcare visits, and the presence of more long-standing comorbid conditions such as back pain, tingling, headaches, temporomandibular joint pain and muscle aches. The investigation of these conditions and the treatment of symptoms lead to patients with IBS consuming over 50% more healthcare resources than matched controls without IBS (Talley et al, 1995; Longstreth et al, 2003). Thus, the costs associated with IBS are impacted by the high prevalence of the disease and the disproportionate use of resources.

Clinical Features of IBS With Predominant Constipation

The cardinal symptoms of IBS-C are abdominal pain or discomfort associated with constipation. The current symptom-based (Rome III) criteria are (Longstreth et al, 2006a)

- Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for at least 3 days per month in the last 3 months, which is associated with 2 or more of the following:

- Improvement with defecation

- Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

- Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

- Supportive symptoms include

- Abnormal stool frequency (< 3 per week)

- Abnormal stool form (lumpy-hard)

- Straining

- Urgency

- A feeling of incomplete evacuation

- Passing mucus and gas

These criteria should be fulfilled for at least 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Abdominal pain associated with changed bowel function is always cited as the cardinal symptom of IBS. However, bloating is very common, especially in women, and is reported by a third of patients as the most important reason for consulting a physician. Bloating is associated with decreased energy, decreased quality of life, and increased use of medications and healthcare utilization (Ringel et al, 2009). Therefore, effective management of these symptoms is important to ensure patient satisfaction and improved quality of life. Indeed, treatment of IBS should be initiated when the symptoms are found to reduce functional status and diminish overall HRQOL and the information provided across HRQOL domains could be useful to develop personalized therapy.

Patients with IBS often experience other GI- and non-GI‒related comorbidities (Table 1) (Whitehead et al, 2002).

Table 1. Comorbidities in Patients With IBS

| Disorder | % Prevalence of IBS in pts with the disorder | % Prevalence of the disorder in pts with IBS |

| GI | ||

| • GERD |

47

|

46.5

|

| • Functional dyspepsia |

28-47

|

28-57

|

| Other somatic disorders | ||

| • Fibromyalgia |

32-77

|

28-65

|

| • Chronic fatigue syndrome |

35-92

|

14

|

| • Chronic pelvic pain |

29-79

|

35

|

| • TPMJ pain |

64

|

16

|

| • Interstitial cystitis |

30.2

|

-

|

Patients also experience a wide range of non-GI symptoms such as:

- Headache: 23%-45%

- Back pain: 27%-81%

- Fatigue: 36%-63%

- Myalgia: 29%-36%

- Dyspareunia 9%-42%

- Urinary frequency: 21%-61%

- Dizziness: 11%-27%

As a result, IBS patients make more healthcare visits and incur more healthcare costs than non-IBS patients. More than half of these are due to non-GI concerns (Whitehead et al, 2002). Moreover, IBS patients with comorbid somatic disorders report more severe IBS symptoms and lower HRQOL (Whitehead et al, 2002).

No criteria have been established to determine severity of IBS, mainly due to the large number of factors that influence severity and the wide gap between patient and physician perceptions of severity. Patients tend to rate severity on multiple symptoms including abdominal pain and discomfort (pain, bloating); defecation-related symptoms (straining); illness-related anxiety (something serious is wrong with me) (Lembo et al, 2005). Therefore, factors that are important to consider when assessing severity include (Lembo et al, 2005; Drossman et al, 2000):

- HRQOL

- Psychosocial factors

- Healthcare use behavior

- Disability

- Overall impact of IBS on the patient's life

Gender Issues

As discussed above, more women have IBS than men, except in Asian countries. Women with IBS tend to report greater overall IBS symptom severity, intensity of abdominal pain and bloating, and impact of symptoms on daily life, and a lower HRQOL (Xiong et al, 2004; Lau et al, 2002). Women also report more extraintestinal symptoms, including nausea, urinary urgency, and dyspareunia and are more likely to report constipation and bloating (Ho et al, 1998; Kwan et al, 2002; Danivat et al, 1988; Masud et al, 2001; Rajendra, Alahuddin, 2004). Symptoms vary according to the menstrual cycle, with increased reporting of GI symptoms (eg, looser stools and rectal sensitivity) in the late luteal and menses phases when compared with the mid-follicular phase (Ghoshal et al, 2008; Han et al, 2006).

Given the lack of biomarkers, the diagnosis of IBS-C is largely based on the fulfillment of symptom-based criteria (Rome III).

However, the overlap with other functional disorders includes CC and functional dyspepsia (Longstreth et al, 2006a; Thompson et al, 1992; Thompson et al, 1999). Organic diseases can present with similar symptoms to those in IBS-C, which can lead to additional tests increasing costs, but not diagnostic yield (eg, complete blood count, full metabolic panel (Furman, Cash, 2011). Using a case vignette for IBS-C, Spiegel showed that the approach to IBS as a disease of exclusion meant that non-IBS experts used 1.3 times more tests and spent $212 per person more in diagnostic expenditure (Spiegel et al, 2010). These results confirm that the likelihood of identifying organic disease with routine laboratory tests is no greater in patients with IBS (without alarm features) than in the general population.

The specificity of the Rome criteria increases when alarm symptoms are included with the GI symptoms (Ford et al, 2008a;Jellema et al, 2009). On average, IBS patients report at least 1.65 red flag symptoms (Whitehead et al, 2006), and those that may mandate further investigation include blood passed per rectum, unintentional weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, nocturnal symptoms, or a significant change in symptoms after a stable pattern over several years. A family history of colorectal cancer, IBD, or celiac sprue also constitutes an alarm feature. Unfortunately, the discriminatory value of these alarm symptoms is disappointing. In these cases, and in patients with late-onset symptoms, a colonoscopy is indicated. It is interesting to note that, in community-based surveys, up to 50% of patients with IBS undergo colonoscopy in the course of their diagnostic evaluation (Talley et al, 1995).

The Rome III guidelines encourage clinicians to make a positive diagnosis of IBS-C on the basis of symptom complexes and emphasize that IBS-C is not a diagnosis of exclusion (Longstreth et al, 2006a).

In making an accurate and quick symptom-led diagnosis, it is essential that the HCP and the patient communicate effectively, but there are several barriers to achieving this. For the patient, there is the embarrassment of discussing intimate bowel symptoms and a feeling of inadequacy. For the HCP, there needs to be empathy with the patient's anxieties and conveying a sense of engagement with their condition. Achievable management goals need to be set that are subsequently reviewed in order for the patient to take a sense of responsibility for their condition (Lacy et al, 2007). In addition, the lag time to make a diagnosis of IBS needs to be reduced. The average time from experiencing symptoms to having a formal diagnosis of IBS is 5 years (International Foundation for Functional GI Disorders).

A validated Patient Daily Diary used on a regular basis would provide an objective log of the patient's symptoms in the lead up to their consultation. Such a diary is provided by the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders.

There are several scenarios in which diagnostic testing is recommended (Speigel et al, 2004a; Brandt et al, 2009):

- Colonoscopy in patients aged > 50 years with new symptoms

- Testing in patients who have not improved despite symptom-based treatment

Thus, the available evidence supports the application of validated symptom-based clinical criteria along with the judicious use of selected high-yield laboratory and endoscopic testing in selected patients.

Patient Dissatisfaction With Current Management and Therapies

Many IBS-C patients initially treat their symptoms with lifestyle modifications such as exercise and exclusion diets together with remedies directed at the symptoms of constipation, including fiber supplements, over-the-counter (OTC) laxatives, and probiotics. Less frequently, they may also pursue various forms of psychotherapy such as relaxation, stress management, cognitive behavior therapy, and hypnosis. Despite these forms of therapy, many IBS patients are dissatisfied with their symptomatic response. This dissatisfaction leads to increased physician consultations, many drug therapies, and multiple changes and adjustments in treatment strategies. .

A recent survey of 657 members of the Intestinal Disease Foundation (IDF), including 420 with IBS, 97% of IBS respondents had required 2 or more healthcare professional consults (visits and telephone) and approximately 75% had made 4 or more such visits/calls in the preceding 3 months (Hulisz, 2004). Many patients try multiple traditional medications in an attempt to find symptom relief. In addition, in the Truth in IBS (T-IBS) Survey more than 50% of IBS sufferers (n = 318) reported that IBS symptoms had a substantial impact on their social activities (eg, going shopping, going out to eat), and 52% reported that IBS negatively affected their sex life or physical relationships (Hungin et al, 2005).

This overall level of patient dissatisfaction is shown in a recent study comparing the patients' ideal expectations vs their actual experience when visiting a physician about their IBS (Table 2) (Halpert et al, 2010).

Table 2. Patient Expectation vs Actual Experience

| Patients' desired qualities | Expectation (% patients) | Actual experience (% ideal met) |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive information | 96% | 38% |

| To answer questions | 96% | 68% |

| To listen | 94% | 64% |

| To support | 87% | 47% |

Thus, there is room for improvement and for physicians to provide the type of care that their IBS-C patients are seeking. The patients' concerns often relate to their misconceptions about the etiology of IBS-C, and this further amplifies the burden of the disease and health-related fears and concerns. For instance, in a survey of 261 patients with IBS, 80.5% believed it results from anxiety, 75.1% believed that it is caused by dietary factors, and 63.5% believed it to be caused by depression. Moreover, 1 in 7 patients believed that IBS-C can progress to cancer, increases the chances of developing IBD, and shortens lifespan. When asked about prescription medications, only 66.7% felt they were effective. Thus, there remains an unmet need for those patients who fail to improve with currently available therapies.

The traditional approach to therapy for IBS-C has largely focused on a patient's predominant or most bothersome symptom(s) (eg, laxatives for constipation and smooth-muscle relaxants for abdominal pain). This approach has its limitations and typically has no impact on the natural history of the disorder (Camilleri et al, 2009b). Complicating the interpretation of response to any treatment, there is a powerful placebo effect (up to 46%) during the first few weeks of therapy (Brandt et al, 2009).

The principles of treating IBS-C in clinical practice are as follows: The most "evidence-based" treatments for IBS are those that influence bowel function. IBS-C patients with delayed transit tend to have greater distension and bloating than those with normal transit. Therefore, drugs that accelerate transit can be expected to improve this troublesome problem

- Secretagogues accelerate small bowel and colonic transit and relieve abdominal symptoms as well as bowel dysfunction

- Despite meta-analyses of antidepressant benefit in IBS overall, the pharmacodynamic and clinical trial evidence is limited in IBS-C

- Probiotics tend to relieve bloating, flatulence, and possibly, pain in IBS, but more data are needed

Bulking agents. Soluble fiber such as psyllium (12-20 g/day) is typically regarded as the first-line treatment for constipation associated with IBS-C. Although commonly used in clinical practice, the evidence for the role of bulking agents in IBS is limited (Brandt et al, 2009; Ford et al, 2008b). Indeed, several studies have shown that insoluble fiber (bran) can aggravate symptoms such as bloating (Miller et al, 2006).

The clinical trials assessing fiber supplements have been evaluated collectively in several systematic reviews with somewhat differing conclusions. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Task Force recently reported their findings from an evidence-based review on the effectiveness of fiber supplements in the management of IBS-C and concluded that psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid (ispaghula husk) is moderately effective at increasing stool frequency and consistency and can be given a conditional recommendation (Grade 2C). However, wheat or corn bran cannot be recommended (Lee, 2010). A recent Cochrane review of 11 studies did not find fiber supplements more effective than placebo in the treatment of IBS (Ruepert et al, 2011).

Osmotic and stimulant laxatives. Osmotic laxatives are often the alternative first line therapy for IBS-C. No placebo-controlled, randomized studies of osmotic laxatives have been published, and most of these agents have been studied only in CC patients. A small study was published that assessed polyethylene glycol (PEG) in 27 postpubertal adolescents with IBS-C, and although it increased the number of bowel movements per week, it had no effect on abdominal pain intensity (Whitehead et al, 1990).

Despite a lack of evidence, stimulant laxatives are commonly recommended by clinicians as a treatment for IBS-C. Although these agents accelerate colonic transit, an important unknown is whether stimulants offer any benefits for abdominal pain in IBS-C patients. There are currently no high-quality studies that have assessed the long-term safety of osmotic or stimulant laxatives in IBS-C patients.

Antispasmodics. Abdominal pain or discomfort are cardinal features of IBS and are thought to be symptoms that are related to alterations in intestinal or colonic smooth-muscle motility and/or visceral hypersensitivity. Because of their effects on smooth-muscle contractile activity, antispasmodics are a mainstay of therapy for the symptoms of IBS-C.

Antispasmodics include antimuscarinics, calcium channel blockers, and anticholinergics. Of these only 4 specific anticholinergics are available in the United States: hyoscine, dicyclomine, belladonna, and propantheline. Hyoscine and peppermint oil are the most effective agents in this class (Whitehead et al, 1990).The clinical utility of these drugs is limited by their side effects (including dry mouth, dizziness, blurry vision, urinary retention, and confusion in the elderly). Moreover, the propensity of these agents to promote constipation makes them relatively contraindicated in patients with IBS-C. (Saad, 2011)

Prokinetic Agents

Serotonergic agents. Tegaserod was the only 5-HT4 receptor agonist available for the treatment of women with IBS-C from 2002 until its voluntarily withdrawal from the market in 2009 due to an unexplained increased incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in the treatment group compared to the placebo group. Although tegaserod's efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of women with IBS-C was readily demonstrated in 3 multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials involving more than 3000 patients (Muller-Lissner et al, 2001; Novick et al, 2002; Lefkowitz et al, 2000), the 13 cardiovascular ischemic events (3 myocardial infarctions, 1 sudden cardiac death, 6 cases of unstable angina, and 3 cerebrovascular accidents) in 11,614 patients treated with tegaserod compared with 1 event in the 7031 patients receiving placebo in a pooled analysis of all the clinical trials (P = .02) could not be explained, leading to its withdrawal from the US and Canadian markets for safety concerns (Thompson, 2007).

Intestinal secretagogues. Lubiprostone is a chloride channel activator with FDA approval for the management of IBS-C. Lubiprostone is available as an 8-μg, twice-daily oral treatment for women with IBS-C. It is an oral bicyclic fatty acid derivative of prostaglandin E1 that selectively activates the type-2 chloride channel located on the apical membrane of human intestinal epithelial cells (Cuppoletti et al, 2004), thereby increasing chloride-rich fluid secretion into the GI tract. Activation increases passive paracellular movement of sodium ions and water and a resultant net increase in fluid secretion into the lumen of the intestine (Cuppoletti et al, 2004) , softening the feces and increasing stool biomass with attendant secondary effects on peristalsis and transit (Lang et al, 2008; Owen, 2008).

The efficacy and tolerability of lubiprostone for the treatment of IBS-C have been assessed in large, high-quality phase 3 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs). Two phase 3, 12-week, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials evaluated lubiprostone in 1171 patients (92% female) meeting the Rome II criteria for IBS-C (Drossman et al, 2009). In these trials, participants were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive lubiprostone 8 μg twice a day. The studies used a rigorous and previously untested primary endpoint. A 7-point Likert scale was employed to answer the following question: "How would you rate your relief of IBS symptoms (abdominal pain/discomfort, bowel habits, and other IBS symptoms) over the past week compared with how you felt before you entered the study?" Those reporting at least moderate relief in 4 of 4 weeks or significant relief in 2 of 4 weeks were considered monthly responders. An overall responder had to be a monthly responder in 2 of the 3 months of the clinical trial. This rigorous endpoint was designed to minimize the placebo effect. In these phase 3 trials, patients randomized to lubiprostone were nearly twice as likely to be responders as those on placebo (18% vs 10%, P =.001). Lubiprostone was also superior to placebo in improving individual IBS symptoms, including abdominal discomfort/pain, stool consistency, straining, constipation severity, and QOL. Lubiprostone 8 μg bid was well tolerated in these trials. The most common treatment-related side effects were nausea (8%), diarrhea (6%), and abdominal pain (5%). There was no difference in serious side effects between those taking lubiprostone or placebo (1% in both groups). The results of the phase 3 clinical trials led the FDA to approve lubiprostone for the treatment of women aged 18 years and older suffering from IBS-C in 2008. An evidence-based systematic review performed by the ACG IBS Task Force concluded that "Lubiprostone in a dose of 8 μg twice daily is more effective than placebo in relieving global IBS symptoms in women with IBC-S (Grade 1B rating)."

A recently published extension study reported a similar safety profile over a period of up to 52 weeks of open-label treatment with lubiprostone (Chey et al, 2012). It was concluded that lubiprostone at a dose of 8 μg bid was safe and well tolerated over 9 to 13 months of treatments. In addition to the side effects already mentioned, there have been rare reports of dyspnea. The mechanism of dyspnea is unclear but it typically occurs within 30 to 60 minutes of taking the first dose, generally resolving in a few hours' time. Occasionally, dyspnea recurs with subsequent dosing.

Lubiprostone carries a pregnancy category C rating because of increased fetal demise in guinea pig studies. The product label recommends documentation of a negative pregnancy test before initiation of therapy and the use of contraception while taking lubiprostone in women with the potential of childbearing.

Low-Dose Antidepressants

Antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) can be considered if abdominal pain does not respond to therapies primarily aimed at improving bowel function. Theoretically, they should provide benefits in IBS by both central and peripheral mechanisms. A recent meta-analysis found that antidepressants as a class were efficacious for the global symptoms of IBS. Few studies of antidepressants have focused on IBS-C patients. One randomized, controlled trial found that the SSRI fluoxetine improved global and individual symptoms in 44 patients with IBS-C (Vahedi et al, 2005). It is important to remember that tricyclic agents can aggravate constipation-related complaints because of their anticholinergic properties.

What to Expect From Future Therapies for IBS-C?

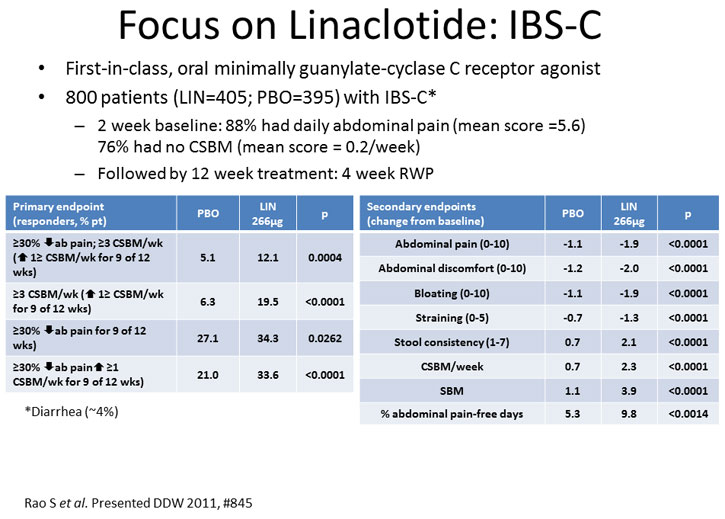

Linaclotide. Linaclotide is a 14-amino acid synthetic peptide that selectively binds to and activates the guanylate cyclase C receptor on the luminal surface of the intestinal epithelium, resulting in the production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (Bryant et al, 2010). Intracellular cGMP results in activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) leading to increased active secretion of chloride and passive paracellular movement of sodium and water into the intestinal lumen leading to improvements in stool frequency, consistency, and intestinal transit. Based upon studies in animals, it has been suggested that extracellular cGMP may reduce visceral hyperalgesia by reducing firing of visceral afferent nerve fibers (Bharucha, Linden, 2010).

Linaclotide is minimally absorbed and orally administered qd. The results of the phase 3, IBS-C, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with up to 26 weeks of treatment were presented at Digestive Diseases Week 2011 (Rao et al, 2011; Chey et al, 2011a; Carson et al, 2011). The phase 3 trials in IBS-C (as defined by modified Rome II criteria) utilized the rigorous interim primary endpoint developed by the FDA for treatment trials in IBS-C. In addition to the FDA interim endpoint, 3 additional primary and 10 secondary endpoints were studied over 12 to 26 weeks (Johnston, Schneier, 2012). Some of the key endpoints assessed in these trials included

- FDA interim endpoint: a responder was defined as a patient who had a ≥ 30% reduction from baseline in abdominal pain at its worst and an increase in complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBMs) of ≥ 1 per week in the same week, for at least 6 of 12 weeks of treatment

- Abdominal pain responder endpoint: a responder had a ≥ 30% reduction from baseline in abdominal pain for at least 9 or 12 weeks of treatment

- CSBM responder endpoint: a responder has ≥ 3 CSBMS per week with an increase in CSBMs of ≥ 1 per week for at least 9 of 12 weeks of treatment

Figure 1.

All primary and secondary endpoints were achieved with sustained efficacy up to 26 weeks (Chey et al, 2011a). Combining the phase 3 data demonstrated improved quality-of-life, as measured by the IBS-QOL scale, in 7 of 8 domains in the linaclotide-treated patients (Carson et al, 2011). Additionally, there was no evidence of rebound or worsening of abdominal pain or bowel symptoms during the randomized withdrawal period (Rao et al, 2011). Linaclotide was generally well tolerated. The most common AE was diarrhea (4% vs 0.2% for linaclotide and placebo, respectively) (Chey et al, 2011a).

Bile acid modulators. Bile acids can alter intestinal and colonic motility and secretion. Recent work has investigated specific bile acid analogs or drugs that alter bile acid reabsorption as novel therapies for IBS-C. The results from a trial that evaluated the effects of chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) on colonic transit and clinical parameters in female IBS-C patients were recently reported. CDCA significantly accelerated overall colonic transit and improved clinical outcomes including stool frequency and stool consistency and facilitated the passage of stool. The most common side effect with CDCA was abdominal cramping/pain, which was reported by over 40% of patients compared with none in the placebo group (Rao et al, 2010b). Further studies to clarify whether lower doses of CDCA might offer benefits to constipation without worsening abdominal pain in IBS-C patients are eagerly awaited.

Alternate, Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM)—What Is Their Place?

In general, there is a lack of large, high-quality studies that support the efficacy of CAM therapies for IBS-C.

A single-center, randomized, double-blind trial compared the probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis to placebo in 34 women with IBS-C (Agrawal et al, 2009). Four weeks of B lactis (125 g of yogurt containing B lactis ingested daily) was superior to placebo in reducing abdominal distention as measured by abdominal inductance plethysmography (P=.02), orocecal transit as measured by hydrogen breath testing (P = .049), and colonic transit as measured by radiopaque marker testing (P =.026). Furthermore, B lactis was superior to placebo in addressing overall IBS symptom severity (P =.032) and abdominal pain (P =.044) with a trend toward improvement in bloating and flatulence.

A Cochrane review of herbal medicines (eg, Padma Lax) for the treatment of IBS-C identified several well-designed clinical studies that showed improvement of IBS symptoms (Lui et al, 2006). It has been suggested that a combination of certain herbs may act synergistically on serotonin and acetylcholine receptors in isolated human intestine, but further studies are required.

PART 2: CHRONIC CONSTIPATION (CC)

Introduction

Constipation is a surprisingly common problem in Western populations and is particularly prevalent in women, children, and older adults. For some patients, constipation is intermittent and requires no, or minimal, intervention while for others, constipation can be life altering and presents a treatment challenge for healthcare providers.

Defining Constipation

Although doctors tend to equate constipation with reduced stool frequency, patients report a wide variety of clinical complaints.

The Rome III criteria embrace the diversity of symptoms experienced by patients with CC, of which stool frequency is only 1 measure (Longstreth, 2006a):

Rome III Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Constipation

Two or more of the following 6 features must be present*:

- Straining during at least 25% of defecations

- Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of defecations

- Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations

- Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25% of defecations

- Manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of defecations (eg, digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor)

- Fewer than 3 defecations/week

*Criteria fulfilled for the previous 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis. In addition, loose stools should rarely be present without the use of laxatives, abdominal pain is not required, and there should be insufficient criteria for IBS. These criteria may not apply when the patient is taking laxatives.

It is important to note that, in a recently reported study, there was a large overlap between functional/chronic constipation and IBS-C, and patients frequently transitioned between these diagnoses over time (Wong et al, 2010). This study reinforces clinical experience that suggests that the lines between IBS-C and CC are often blurred, suggesting that IBS-C and CC represent a spectrum of disease rather than 2 separate and distinct clinical entities.

Epidemiology and Burden of Illness

The prevalence of constipation ranges from 2% to 28% in Western countries and, as with IBS-C, the value varies depending on the population demographics and the definition of constipation. In general, the prevalence is highest when constipation is self-reported and lowest when the Rome II criteria for functional constipation are applied, possibly because effects of gender, race, socioeconomic status, and level of education on the prevalence of constipation are reduced (Higgins, Johanson, 2004). The prevalence of self-reported constipation is higher in women than men (pooled odds ratio [OR] based on 45 studies = 2.22, 95% CI: 1.87–2.62) and in older adults (pooled OR based on 3 studies for persons > 60 years of age = 1.41 (1.17–1.70) (Suares, Ford, 2011b; Gallegos-Orozco et al, 2012). Indeed, in nursing home residents/hospitalized older patients, 50% to 74% use laxatives on a daily basis (Gage et al, 2010). Constipation can be complicated by fecal impaction and incontinence, particularly in older people who are immobile, have cognitive problems, and need help to get to the toilet (Gallagher, O'Mahony, 2009).

Constipation results in more than 2.5 million physician visits, 92,000 hospitalizations, and several hundred million dollars of laxative sales/year in the United States (Lembo et al, 2010b).

In an analysis of physician visits for constipation in the United States between 1958 and 1986:

- 31% of patients were seen by general and family practitioners

- 20% were seen by an internist

- 9% visited a surgeon

- 9% consulted an obstetrician-gynecologist

- 4% were seen by a gastroenterologist

Factors Contributing to Constipation

The risk factors for constipation include

- Advanced age

- Female gender

- Low level of education

- Low level of physical activity

- Low socioeconomic status

- Nonwhite ethnicity

- Use of certain medications

Mechanical small and large bowel obstruction, medications, and systemic illnesses can cause constipation, and these causes of secondary constipation must be excluded, especially in patients presenting with a new onset of constipation. These are summarized below:

- Mechanical obstruction

- Colorectal cancer

- Rectocele or sigmoidocele

- Anal stenosis

- Stricture

- Medications, such as

- Calcium containing antacids and calcium supplements

- Anticholinergics including antispasmodics

- Calcium channel blockers

- Anticonvulsants

- TCAs

- Iron supplements

- Opioids

- Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Metabolic disorders

- Diabetes

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypercalcemia/electrolyte disturbance

- Other conditions

- Pregnancy

- Diabetes

- Depression

- Eating disorders

- Multiple sclerosis

- Dementia

- Spinal cord injury/stroke

- Parkinson's disease

Classification of Constipation

Functional constipation can be divided into 3 broad categories with the following clinical features (Schiller, 2001; Mertz et al, 1999)

- Normal-transit constipation: 59% to 71% of patients with functional constipation

- Differs from IBS in that abdominal pain is not a predominant feature in functional constipation

- Slow-transit constipation: 11% to13% of patients with functional constipation

- Common in young women and with associated disordered colonic function that leads to hard, small stools that fail to produce sufficient rectal pressure to trigger defecation. Though it is widely held that reduced stool frequency identifies patients with slow transit constipation, the literature does not fully support this dogma. On the other hand, there is literature to support a correlation between hard stool consistency and slow transit constipation (Saad et al, 2010)

- Colonic inertia is a term often used to describe patients with severe forms of this type of constipation

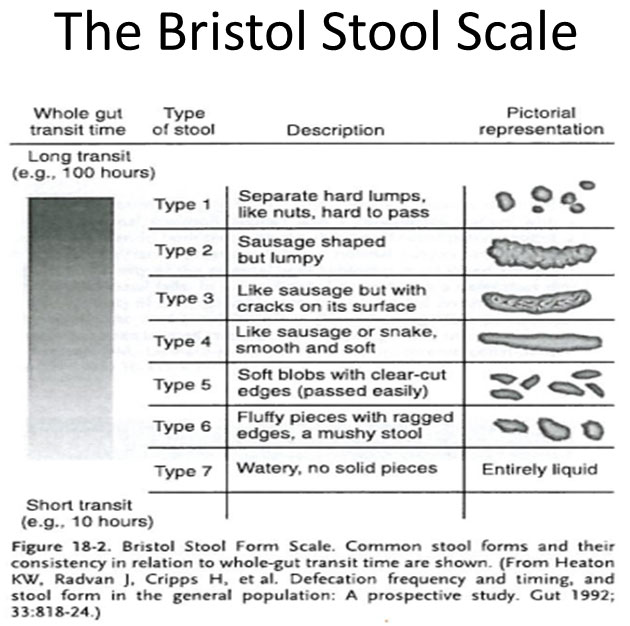

The Bristol Stool Scale is used to describe stool form and it also predicts whole-gut and colonic transit time as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

- Defecatory or rectal evacuation disorders:13% to 28% of patients with functional constipation:

- Normal defecation requires a series of coordinated physiologic actions that allow expulsion of stool from the rectum: contraction of the abdominal wall muscles, relaxation of the puborectalis muscles, descent of the pelvic floor with straightening of the anorectal angle, and relaxation of the external anal sphincter. Failure of one or more of these actions can lead to defecatory dysfunction or dyssynergic defecation

- Disorders of the pelvic floor:

- Rectocele: a bulging of the rectum through the anterior rectal wall often caused at childbirth. They can occur in asymptomatic women, but those experiencing symptoms typically report a sensation of incomplete evacuation, perineal pain, sensation of local pressure, and a bulge at the vaginal opening on straining. Vaginal splinting may be required to facilitate defecation

- Diminished rectal sensation: this can occur as a consequence of neuropathy (ie, diabetes mellitus or spinal cord injury) or from rectal dilation in the setting of recurrent fecal loading from CC

- Other structural abnormalities such as an enterocele, rectal intussusceptions, or prolapse can lead to difficult defecation and a chronic sensation of incomplete evacuation

Clinical Assessment

It is important to fully understand what the patient means when reporting constipation. A detailed history that includes the duration of symptoms, frequency of bowel movements, and associated symptoms such as abdominal discomfort and distention should be obtained. The history should include an assessment of stool consistency, stool size, and degree of straining during defecation and whether or not bleeding has been seen by the patient. A few clinical features can help distinguish between CC patients with slow colonic transit and dyssynergic defecation. Features of the history that should prompt consideration of dyssynergic defecation include a sensation of incomplete evacuation, excessive straining even when stools are soft or loose, the need for digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation, and failure to respond to traditional laxative therapies

Other areas to cover in the clinical assessment include

- Dietary history – daily fiber and fluid intake

- Past medical history – particularly obstetric and surgical histories

- Social history – behavioural background, depression etc

- Physical examination

- Rectal examination

The presence of warning symptoms or signs, such as unintentional weight loss, rectal bleeding, and family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, should be elicited. A long duration of symptoms that have been refractory to conservative measures is suggestive of a functional colorectal disorder. By contrast, the new onset of constipation, particularly in patients aged 50 years and older, may indicate a more "organic" disease process and thus should prompt early evaluation with colonoscopy. The finding of unexplained iron deficiency anemia should also prompt early evaluation with colonoscopy and in selected cases, upper endoscopy.

Lifestyle modifications. Commonly employed lifestyle modifications include increased intake of dietary fiber, fluid intake, and exercise. There is a pervasive belief that low dietary fiber and fluid intake promote constipation. However, a review of studies assessing dietary fiber and fluid intake found no differences between those with constipation and controls (Mueller-Lissner et al, 2005). Furthermore, dietary fiber typically consists of bran and other insoluble fiber compounds that frequently lead to excessive gas production. On the other hand, several epidemiologic studies suggest an inverse relationship between physical activity and the incidence of constipation (Brown et al, 2000; Kinnunen, 1991; Donald et al, 1985). With this in mind, several poor-quality clinical trials suggest a benefit of increased dietary fiber intake, fluid intake, and physical activity in addressing constipation although benefits appear largely confined to those with mild constipation symptoms (Anti et al, 1998; Sturtzel, Elmadfa, 2008; Graham et al, 1982; De Schryver et al, 2005; Karam, Nies, 1994).

Biofeedback. For dyssynergic defecation or rectal sensory abnormalities, biofeedback provides a retraining of anorectal as well as pelvic floor sensation and re-establishes proper, coordinated muscle function within these structures during defecation. The efficacy of biofeedback has been demonstrated in several RCTs (Rao et al, 2009; Rao et al, 2010a; Simon, Bueno, 2009). There have been no reports of adverse effects associated with biofeedback. A recent meta-analysis of the RCTs found biofeedback effective in providing global satisfaction for the symptoms associated with dyssynergic defecation; however, significant heterogeneity existed with regard to the therapy employed and trial design among the published studies (Maneerattaporn et al, 2011b).

Pharmacological treatment. Medications for CC can be categorized into bulk-forming agents, stool softeners and emollients, osmotic agents, stimulants, intestinal secretagogues, prokinetics, and bile acid modulators.

Bulk-forming agents. These agents consist of a variety of natural and synthetic fiber supplements treating constipation through one or more of several mechanisms including increasing the water retention capacity of stool, bulking the stool, and/or accelerating colon transit. Water soluble agents include psyllium (ispaghula husks), calcium polycarbophil, methylcellulose, insulin, and wheat dextrin. Common water insoluble agents include bran, flax seed, rye, and variety of other nondigestable seeds and vegetables. Psyllium is the best-studied soluble bulking agent demonstrating superiority over placebo at improving global symptoms of constipation (Fenn et al, 1986), increasing number of daily bowel movements, and normalizing defecation (Nunes et al, 2005) in RCTs of low quality. Overall, soluble fiber analogs appear more effective and better tolerated than insoluble fiber products (Suares, Ford 2011a; Brandt et al, 2005; Ramkumar, Rao, 2005). Adequate fluid intake is required for bulk-forming agents to work properly; otherwise a paradoxic response may occur including bowel obstruction. Bulking agents should be started at low doses and gradually titrated to desired effect. Common side effects of bloating, excessive gas production, and abdominal distention can be limiting.

Stool softeners and emollients. Dioctyl sulfosuccinate is the most commonly prescribed stool softener, commercially available as either ducosate sodium or ducosate calcium. Being an anionic detergent, ducosate softens the stool by lowering the surface tension of stool, allowing water to penetrate. Four RCTs s have been published, three comparing ducosate to placebo with inconsistent findings (Castle et al, 1991; Fain et al, 1978; Hyland, Foran, 1968) and one comparing ducosate to psyllium with psyllium demonstrating superiority at increasing stool frequency (McRorie et al, 1998). Although considered safe with few side effects, stool softeners are minimally effective in treating the symptoms of CC. Hence, the use of these agents should generally be confined to patients with mild or infrequent constipation symptoms.

Mineral oil is the most common emollient used in the treatment of constipation. Its use is anecdotal as no clinical trials have been performed assessing its efficacy in the treatment of CC. In addition to the unpleasantness associated with its use, there are reports of aspiration and lipoid pneumonia with its use (Zanetti et al, 2007). The level of evidence for use of mineral oil as a treatment of CC is poor.

Osmotic agents. Osmotic agents are useful when first-line bulk-forming agents or stool softeners prove ineffective. Agents such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose, sorbitol, and magnesium hydroxide create a poorly absorbed luminal osmotic load that results in net intestinal water secretion with consequent effects on stool consistency, fecal biomass, and colonic transit.

PEG has the strongest evidence for its use, with multiple high-quality RCTs demonstrating significant benefits for stool frequency and consistency vs placebo in patients with CC. There are also data from RCTs that suggest that PEG is more effective and better tolerated than lactulose in patients with CC. However, PEG can cause nausea, flatulence, and diarrhea, especially in the elderly, and the dosage should be titrated upward according to clinical response (Brandt 2005).

The efficacy of lactulose has been shown in several RCTs including 3 high-quality RCTs comparing lactulose to placebo (Bass, Dennis, 1981; Sanders, 1978; Wesselius-De Casparis et al, 1968). Although a recent meta-analysis of 10 RCTs comparing PEG to lactulose found PEG to be superior to lactulose at increasing stool frequency, stool form, and relief of abdominal pain (Lee-Rocichaud et al, 2010). The use of magnesium hydroxide for CC is anecdotal as no placebo-controlled RCTs have been published. Although generally safe and likely effective in mild constipation symptoms, care must be exercised with its use in chronic renal disease, given the risk of hypermagnesemia.

Stimulants. A variety of stimulant laxatives are in use including the anthraquinones (senna and cascara), diphenylmethanes (bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate), and misoprostol. Their primary effect on the colon is the stimulation of peristalsis either by direct irritation of the colonic wall or stimulation of sensory nerves on the colonic mucosa. Some stimulants are also believed to inhibit water absorption in the colon. Their onset is rapid, oftentimes stimulating defecation within 6 to 12 hours of dosing. There are 2 recent large, high-quality RCTs s demonstrating superiority of sodium picosulfate (Mueller-Lissner et al, 2010) and bisacodyl (Kamm et al, 2011) over placebo in the treatment of CC. The use of cascara and senna is largely based on anecdotal evidence as no placebo-controlled RCTs have been published in the treatment of CC. Overall, the safety of long-term stimulant laxative use is unknown. Side effects including diarrhea, cramping, bloating, and nausea can be limiting. Misoprostol has been shown to be superior to placebo regarding transit time, bowel frequency, and stool weight in a single, small RCT (Soffer et al, 1994). However, misoprostol often causes dose-dependent side effects including nausea and abdominal cramping and carries an FDA pregnancy category X.

Intestinal secretagogues. Lubiprostone. As described above, lubiprostone is a novel bicyclic fatty acid that activates the chloride 2 channel, thereby increasing intestinal fluid secretion and transit (Camilleri et al, 2006) without altering serum electrolyte levels. In 2 phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled trials, lubiprostone 24 μg bid increased the number of spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs) in patients with CC as defined by the Rome II criteria. Lubiprostone improved consistency and reduced overall severity of symptoms. The frequency of spontaneous bowel movements increased in men and women as well as older patients who took the drug. A rebound effect after withdrawal of the drug was not observed (Saad, Chey, 2008). Lubiprostone 24 μg bid was approved by the FDA in 2006 for the treatment of men and women with CC. The most common side effects were nausea, headache, and diarrhea. Nausea is a dose-dependent side effect of lubiprostone. Roughly 30% of patients starting the higher dose of 24 μg bid will report some degree of nausea. In contrast, only 8% of patients taking the lower dose of 8 μg bid, which is FDA approved for the treatment of IBS-C patients, reported nausea. Most nausea associated with lubiprostone is mild and transient. The incidence of nausea can be minimized by dosing this medication with food.

Newer Products

Prokinetics. Prucalopride. Three large, 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials of similar design have evaluated the efficacy and safety of prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg qd vs placebo in patients with CC (Camilleri et al, 2008; Quigley et al, 2009; Tack et al, 2009). Patients enrolled in these studies were required to have ≤ 2 CSBMs/week, in combination with straining, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, or hard stools, at least 25% of the time. When the results of the phase III studies (N = 1924) were combined, the percentage of patients with an average of at least 3 CSBMs/week over the 12-week treatment period was 23.6%, 24.7%, and 11.3% for prucalopride 2 mg, prucalopride 4 mg, and placebo, respectively (P < .005). Patients from the three pivotal trials were entered into a 24 month open label follow up study. Eighty –six percent of patients who completed these studies continued prucalopride (n=1455, 90% female). Improvement in the average PAC-QOL satisfaction score observed after 12 weeks prucalopride was maintained during the open-label treatment for up to 18 months. Only 10% of patients who had normalized bowel function on prucalopride at the end of the pivotal trials discontinued due to insufficient response during the open-label treatment. Gastrointestinal events and headache caused discontinuation of prucalopride treatment in ~5% of patients (Camilleri M, Van Outryve MJ, Beyens G et al. Clinical trial: the efficacy of open –label prucalopride treatment in patients with chronic constipation – follow up of patients from the pivotal studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 32 (9): 1113-23).

The most frequent adverse effects were headaches, nausea, and diarrhea, which tended to occur soon after initiation and to be transient. In a safely assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation, prucalopride was well tolerated with no differences from placebo in electrocardiogram (ECG) or a range of Holter-monitoring parameters (Camilleri et al, 2009a). Unlike cisapride and tegaserod, prucalopride does not interact with hERG potassium or 5HT1b channels—both postulated to play a role in potential adverse cardiovascular outcomes (Tack et al, 2012). This agent is available for the treatment of women with CC in Canada and many countries in Europe but not in the United States.

Products in Development

Linaclotide. Two randomized, 12-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (trials 303 and 01) have been reported involving 1276 patients with CC (Lembo et al, 2011b). Patients received either linaclotide 145 μg or 290 μg qd for 12 weeks or placebo. The primary endpoint was 3 or more CSBMs per week and an increase of 1 or more CSBMs from baseline during at least 9 of the 12 study weeks.

For trials 303 and 01, respectively, the primary endpoint was achieved by 21.2% and 16.0% of the patients who received linaclotide 145 μg, and by 19.4% and 21.3% of patients who received linaclotide 290 μg, as compared with 3.3% and 6.0% of those who received placebo (P < 0.01 for all comparisons vs placebo). The improvements with all key secondary endpoints were significantly greater with linaclotide vs placebo.

The incidence of AEs was similar among all study groups, with the exception of diarrhea, which led to discontinuation in 4.2% of patients at both doses of linaclotide as compared to 0.5% of patients receiving placebo.

The authors concluded that in these two 12-week trials, linaclotide significantly reduced bowel and abdominal symptoms in patients with CC. Linaclotide is currently under review by the US FDA as a treatment for patients with CC and IBS-C.

Bile acid modulators. Increasing colonic bile acids might offer a novel strategy to improve CC. A3309 is a novel small molecule that inhibits ileal bile acid transporters, resulting in greater delivery of bile acids to the right colon with consequent effects on motility, transit, and secretion. A3309 has been shown to accelerate colon transit in animals and humans (Maneerattanaporn et al, 2011a). A recent phase 2b clinical trial in 190 CC patients demonstrated that A3309 at doses of 10 and 15 mg per day, but not 5 mg per day, significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous bowel movements (SBM) after 1 week (primary endpoint) and over the entire 8 week randomization period. A3309 also reduced the time to first SBM and complete SBM, improved stool consistency, and decreased straining compared to placebo (Chey et al, 2011b). An interesting incremental clinical benefit of A3309 was that it decreased serum lipid levels. The most common side effects with A3309 were abdominal pain and diarrhea, which occurred most commonly in the 15-mg dosing group.

CAM for CC

Several recent studies have evaluated CAM therapies in patients with CC. Attaluri and colleagues recently reported a single-blind randomized, cross-over trial in 40 constipated patients, which evaluated the benefits of prunes (50 g or ~6 prunes bid) or psyllium (11 g bid) for 3 weeks. The primary outcome of mean CSBMs per week as well as stool consistency improved to a greater degree with the prunes compared to psyllium (Attaluri et al, 2011). Palatability and tolerability were similar between groups. In another study of 20 constipated patients, artichokes laced with the probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei IMPC 2.1 (2 × 1010 CFU daily) for 15 days were more effective than ordinary artichokes at improving stool consistency and overall constipation symptoms (Riezzo et al, 2012). Safety data were not reported in this trial. A third randomized, double-blind trial from Hong Kong found that hemp seed pill at a dose of 7.5 g bid for 8 weeks was more effective than placebo at increasing weekly CSBM rates, straining, and need for rescue therapy (Cheng et al, 2011). Side effects including abdominal pain/cramping, bloating, diarrhea, or gas were reported more commonly in the hemp seed than placebo group (13.3% vs 3.3%).

Putting the Evidence Into Clinical Perspectives

As described above, it is increasingly recognized that there is substantial overlap between IBS-C and CC, and these groups are not as distinct as previously thought (Wong et al, 2010). Indeed, drugs such as lubiprostone, prucalopride, and linaclotide have been shown in clinical trials to be effective for both IBS-C and CC.

In this final section, we look at a patient with features that demonstrate this overlap between IBS-C and CC, and we consider an appropriate management strategy.

PART 3: CLINICAL VIGNETTE

A 51-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician for a several year history of progressive constipation symptoms failing several trials of fiber supplements, OTC stool softeners, and several osmotic laxatives. She describes the passage of hard stool (Bristol type 1-2), irregular bowel movement, with her occasionally going 4 days' time without a bowel movement. She also reports straining, bloating, and a generalized lower abdominal and back pain that worsens when she has gone more than 2 days without a bowel movement.

Her past medical and family history is unremarkable. Her physician notes mild lower abdominal tenderness to palpation with an otherwise normal physical examination. A rectal examination is not performed. Following a pregnancy test, the woman is given a prescription for lubiprostone 8 µg to be taken bid with food. A colonoscopy is performed, which is only remarkable for small external hemorrhoids. The woman reports a poor response to the lubiprostone after a 1-month trial of this therapy. It is increased to 24 µg bid with no improvement in her symptoms.

Given her refractory symptoms, she is referred to a gastroenterologist. Further questioning by the gastroenterologist reveals additional symptoms including a sensation of incomplete emptying, sense of anal blockage during straining, and the occasional placement of a digit into the anal canal to initiate a bowel movement. A rectal examination is performed and is notable for a normal resting and squeeze tone. With valsalva, there is a paradoxic increase in the external anal sphincter tone as well as a poor relaxation of the puborectalis muscle (a lack of straightening of the rectal vault is appreciated by the examining digital during valsalva). These physical findings suggest a condition of dyssynergic defecation. This suspected diagnosis is further supported by an abnormal balloon expulsion test. The woman was unable to expel the rectal balloon within a 60-second time frame.

She is continued on an osmotic laxative to keep her stool soft and referred to physical therapy to receive biofeedback training. Following 2 months of physical therapy, she reports considerable improvement in her bowel symptoms and resolution of the abdominal pain, back pain, and bloating. She is no longer using an osmotic laxative and continues the bowel program that she learned through her physical therapy.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢