N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2506-2514June 26, 2014DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1208795

The traditional goals of intensive care are to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with critical illness, maintain organ function, and restore health. Despite technological advances, death in the intensive care unit (ICU) remains commonplace. Death rates vary widely within and among countries and are influenced by many factors.1 Comparative international data are lacking, but an estimated one in five deaths in the United States occurs in a critical care bed.2

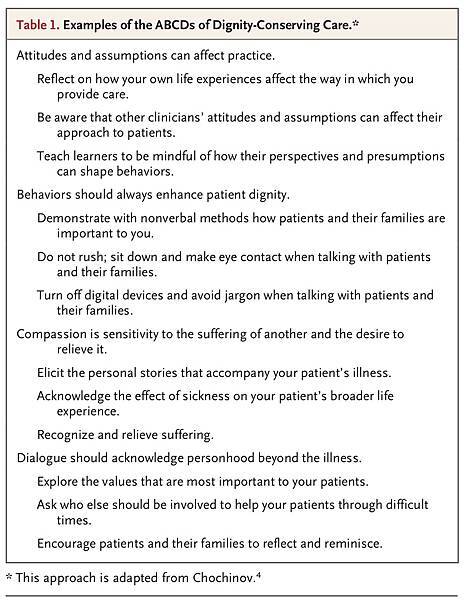

In this review, we address the concept of dignity for patients dying in the ICU. When the organ dysfunction of critical illness defies treatment, when the goals of care can no longer be met, or when life support is likely to result in outcomes that are incongruent with patients' values, ICU clinicians must ensure that patients die with dignity. The definition of “dying with dignity” recognizes the intrinsic, unconditional quality of human worth but also external qualities of physical comfort, autonomy, meaningfulness, preparedness, and interpersonal connection.3Respect should be fostered by being mindful of the “ABCDs” of dignity-conserving care (attitudes, behaviors, compassion, and dialogue)4 (Table 1

).

Preserving the dignity of patients, avoiding harm, and preventing or resolving conflict are conditions of the privilege and responsibility of caring for patients at the end of life. In our discussion of principles, evidence, and practices, we assume that there are no extant conflicts between the ICU team and the patient's family. Given the scope of this review, readers are referred elsewhere for guidance on conflict prevention and resolution in the ICU.5,6

The concept of dying with dignity in the ICU implies that although clinicians may forgo some treatments, care can be enhanced as death approaches. Fundamental to maintaining dignity is the need to understand a patient's unique perspectives on what gives life meaning in a setting replete with depersonalizing devices. The goal is caring for patients in a manner that is consistent with their values at a time of incomparable vulnerability, when they rarely can speak for themselves.7 For example, patients who value meaningful relationships may decline life-prolonging measures when such relationships are no longer possible. Conversely, patients for whom physical autonomy is not crucial may accept technological dependence if it confers a reasonable chance of an acceptable, albeit impaired, outcome.8 At issue is what each patient would be willing to undergo for a given probability of survival and anticipated quality of life.

ON THE NEED FOR PALLIATIVE CARE

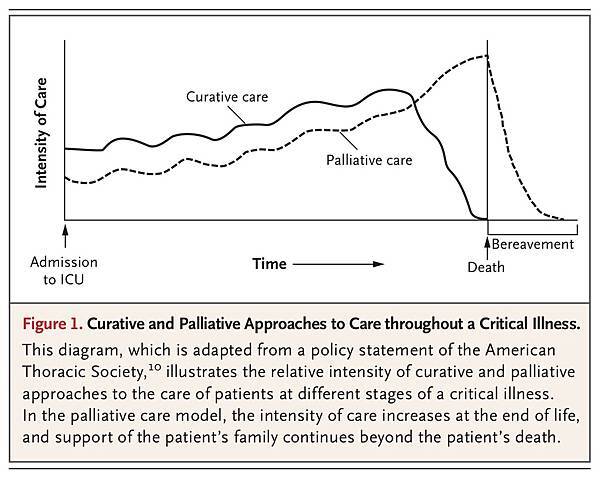

The coexistence of palliative care and critical care may seem paradoxical in the technological ICU. However, contemporary critical care should be as concerned with palliation as with the prevention, diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of life-threatening conditions.

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.”9Palliative care, which is essential regardless of whether a medical condition is acute or chronic and whether it is in an early or a late stage, can also extend beyond the patient's death to bereaved family members10 (Figure 1).

ELICITING THE VALUES OF PATIENTS

Sometimes it is too late. A precipitating event prompting an ICU admission that occurs within a protracted downward trajectory of an illness may be irreversible. When clinicians who are caring for a patient in such a scenario have not previously explored whether the patient would want to receive basic or advanced life support, the wishes of the patient are unknown, and invalid assumptions can be anticipated. Effective advance care planning, which is often lacking in such circumstances, elicits values directly from the patient, possibly preventing unnecessary suffering associated with the use of unwelcome interventions and thereby preserving the patient's dignity at the end of life.

Regardless of the rate and pattern of decline in health, by the time that patients are in the ICU, most cannot hold a meaningful conversation as a result of their critical condition or sedating medications. In such cases, family members or other surrogates typically speak for them. In decisions regarding the withdrawal of life support, the predominant determinants are a very low probability of survival, a very high probability of severely impaired cognitive function, and recognition that patients would not want to continue life support in such circumstances if they could speak for themselves.11 Probabilistic information is thus often more important than the patient's age, coexisting medical conditions, or illness severity in influencing decisions about life-support withdrawal.

Discussions can be initiated by eliciting a narrative from patients (or more commonly, from family members) about relationships, activities, and experiences treasured by the patient. The use of engaging, deferential questions, such as “Tell me about your . . .” or “Tell us what is important to . . . ,” is essential. Clinician guidance for constructing an authentic picture of the incapacitated patient's values is offered in the Facilitated Values History,8 a framework that provides clinicians with strategies for expressing empathy, sensitively depicting common scenarios of death, clarifying the decision-making role of surrogates, eliciting and summarizing values most relevant to medical decision making, and linking these values explicitly to care plans.

COMMUNICATION

Before a critical illness develops, patients' perceptions about what matters most for high-quality end-of-life care vary, but human connections are key. Many seriously ill elderly patients cite effective communication, continuity of care, trust in the treating physician, life completion, and avoidance of unwanted life support.12 After critical illness develops, most patients or their surrogates find themselves communicating with unfamiliar clinicians in a sterile environment at a time of unparalleled distress. Challenges in communication are magnified when patients die at an early stage of critical illness, before rapport has been well established.

Clear, candid communication is a determinant of family satisfaction with end-of-life care.13Notably, measures of family satisfaction with respect to communication are higher among family members of patients who die in the ICU than among those of ICU patients who survive, perhaps reflecting the intensity of communication and the accompanying respect and compassion shown by clinicians for the families of dying patients.14 The power of effective communication also includes the power of silence.15 Family satisfaction with meetings about end-of-life care in the ICU may be greater when physicians talk less and listen more. 16

DECISION MAKING

Decision-making models for the ICU vary internationally but should be individualized. At one end of the continuum is a traditional parental approach, in which the physician shares information but assumes the primary responsibility for decision making. At the other end of the continuum, the patient makes the decisions, and the physician has an advisory role. In North America and in some parts of Europe,17 the archetype is the shared decision-making model, in which physicians and patients or their surrogates share information with one another and participate jointly in decision making.18

Although preferences for decision-making roles vary among family members,19 physicians do not always clarify family preferences.20 Family members may lack confidence about their surrogate decision-maker role, regardless of the decision-making model, if they have had no experience as a surrogate or no prior dialogue with the patient about treatment preferences.21 Decision-making burden is postulated as a salient source of strain among family members of patients who are dying in the ICU; anxiety and depression are also prevalent.22,23

PROVIDING PROGNOSTIC INFORMATION

Valid prognostic information is a fundamental component of end-of-life discussions. Understanding the predicted outcome of the critical illness and recognizing the uncertainty of that prediction are helpful in making decisions that reflect the patient's values. However, when it comes to prognosticating for seriously ill patients, families and physicians sometimes disagree.24In one study, surrogate decision makers for 169 patients in the ICU were randomly assigned to view one of two videos of a simulated family conference about a hypothetical patient.25 The videos varied only according to whether the prognosis was conveyed in numerical terms (“10% chance of survival”) or qualitative terms (“very unlikely to survive”). Numerical prognostic statements were no better than qualitative statements in conveying the prognosis. However, on average, surrogates estimated twice as often as physicians that the patient would survive.

In another study, when 80 surrogates of patients in the ICU interpreted 16 prognostic statements, interviews suggested an “optimism bias,” in which the surrogates were likely to interpret the physicians' grim prognostication as positive with respect to the patient's condition.26 Clinicians should recognize that family members who are acting as spokespersons for patients in the ICU are often “living with dying” as they face uncertainty while maintaining hope.27 Hope should be respected during prognostic disclosure28 while a realistic view is maintained, an attitude that is aptly expressed by the simple but profound notion of “hoping for the best but preparing for the worst.”29

MAKING RECOMMENDATIONS

Physicians in the ICU sometimes make recommendations to forgo the use of life-support technology. In one study involving surrogates of 169 critically ill patients, 56% preferred to receive a physician's recommendation on the use of life support, 42% preferred not to receive such a recommendation, and 2% stated that either approach was acceptable.30 A recent survey of ICU physicians showed that although more than 90% were comfortable making such recommendations and viewed them as appropriate, only 20% reported always providing recommendations to surrogates, and 10% reported rarely or never doing so. 31 In this study, delivering such recommendations was associated with perceptions about the surrogate's desire for, and agreement with, the physician's recommendations. Other potential influences are uncertainty, personal values, and litigation concerns.

Asking families about their desire for recommendations from physicians can be a starting point for shared deliberations about care plans.32 Eliciting preferences for how patients or their families wish to receive information, particularly recommendations concerning life support, is not an abnegation of responsibility but rather an approach that is likely to engender trust. Physicians should judiciously analyze each situation and align their language and approach with the preferred decision-making model, understand interpersonal relationships, and avoid overemphasizing a particular point of view. For example, in the shared decision-making model of care for dying patients, family discussions typically include a review of the patient's previous and present status and prognosis, elicitation of the patient's values, presentation of the physician's recommendations, deliberations, and joint decision making about ongoing levels of care.

PROVIDING HOLISTIC CARE

Cultivating culturally and spiritually sensitive care is central to the palliative approach. The pillars of both verbal and nonverbal communication are crucial. Conscious nonverbal communication is rarely practiced yet can be as powerful as verbal communication during end-of-life decision making. Physicians should be aware of the cultural landscape reflecting an institution's catchment area, how cultural norms can influence admissible dialogue, and what is desirable versus dishonoring in the dying process.33

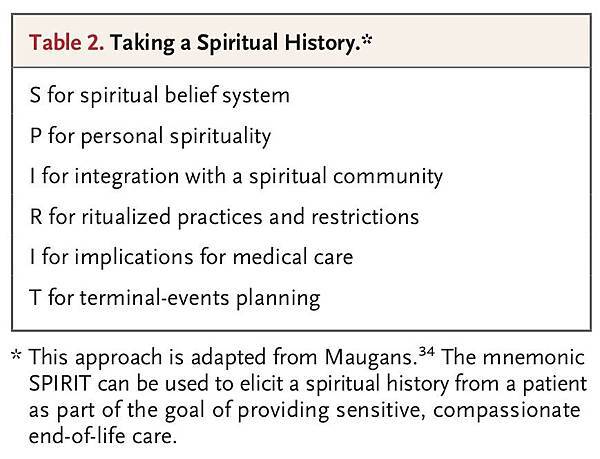

The meaning assigned to critical illness, particularly when death looms, is frequently interpreted through a spiritual lens. For many people, critical illness triggers existential questions about purpose (of life, death, and suffering), relationships (past, present, and future), and destiny. Clinicians should be able to pose questions about spiritual beliefs that may bear on experiences with respect to illness. Introductory queries can open doors, such as “Many people have beliefs that shape their lives and are important at times like this. Is there anything that you would like me to know?”34 A useful mnemonic for obtaining ancillary details is SPIRIT, which encompasses acknowledgment of a spiritual belief system, the patient's personal involvement with this system, integration with a spiritual community, ritualized practices and restrictions, implications for medical care, and terminal-events planning34 (Table 2).

Although it is unrealistic to expect that clinicians will be familiar with the views of all the world religions regarding death, they should be cognizant of how belief systems influence end-of-life care.35 Physicians may recommend different approaches to similar situations, depending on their religious and cultural backgrounds, as has been self-reported36 and documented in observational studies.37 Insensitivity to faith-based preferences for discussion and decision making may amplify the pain and suffering of both patients and their families. Clinicians should understand how spirituality can influence coping, either positively or negatively.38 Chaplains are indispensable for addressing and processing existential distress, conducting life review, and facilitating comforting prayers, rituals, or other observances.

THE FINAL STEPS

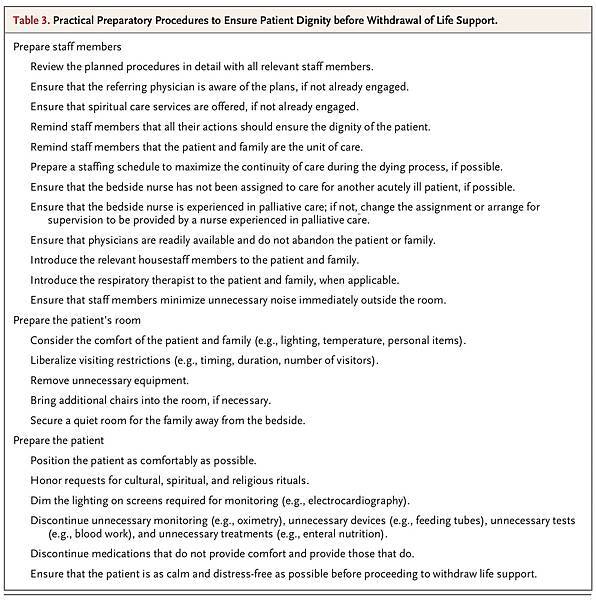

If a shift is made in the goals of care from cure to comfort, it should be orchestrated with grace and should be individualized to the needs of the patient.39 Before proceeding with end-of-life measures, it is necessary to prepare staff members and the patient's room, as well as the patient (Table 3).

The panoply of basic and advanced life-support equipment and the mechanics of their deployment or discontinuation are chronicled in multiple studies, as well as in discussion documents, consensus statements from professional organizations, and task-force reports.10,17,32,40 Strategies should be openly discussed and informed by the same balance of benefits, burdens, and respect for the preferences of patients and their surrogates that apply to other aspects of end-of-life care.10

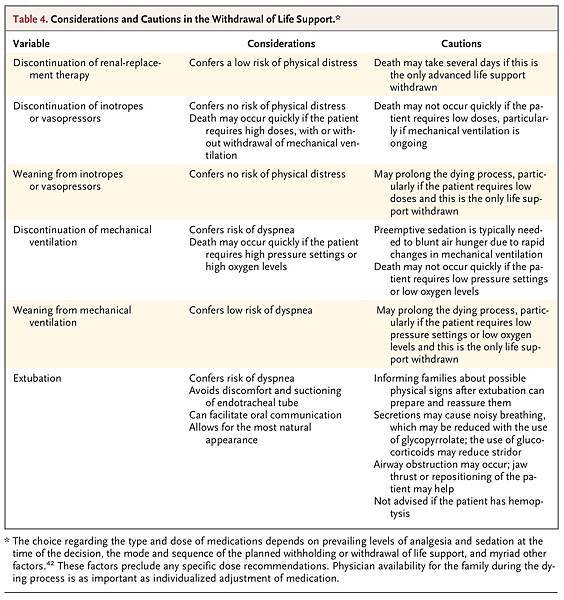

There is no single, universally accepted technical approach. Admissible strategies in most settings include variations and combinations of non-escalation of current interventions, withholding of future interventions, and withdrawal of some or all interventions, except those needed for comfort. When life-support measures are withdrawn, the process of withdrawal — immediate or gradual discontinuation — must be considered carefully. Mechanical ventilation is the most common life-support measure that is withdrawn. 11 However, even in the case of mechanical ventilation, legal or faith-based requirements, societal norms, and physician preferences influence decisions about withdrawal.32 The initiation of noninvasive ventilation with clear objectives for patients who are not already undergoing mechanical ventilation can sometimes reduce dyspnea and delay death so that the patient can accomplish short-term life goals.41 Whatever approach is used, individualized pharmacologic therapy, which depends on prevailing levels of analgesia and sedation at the time of decisions to forgo life support, should ensure preemptive, timely alleviation of dyspnea, anxiety, pain, and other distressing symptoms.42 Clinicians can mitigate the stress of family members by discussing what is likely to happen during the dying process (e.g., unusual sounds, changes in skin color, and agonal breathing). Physician attendance is paramount to reevaluate the patient's comfort and talk with the family as needed (Table 4).

CONSEQUENCES FOR CLINICIANS

Dying patients and their families in the ICU are not alone in their suffering. For some clinicians, views about the suitability of advanced life support that diverge from those of the patient or family can be a source of moral distress. Clinicians who detect physical or psychic pain and other negative symptoms may suffer indirectly, yet deeply. Vicarious traumatization results from repeated empathic engagement with sadness and loss,43 particularly when predisposing characteristics amplify clinicians' response to this workplace stress. Clinicians should be aware of how their emotional withdrawal or lability and “compassion fatigue” can jeopardize the care of dying patients and their families.

Informal debriefing or case-based rounds,44 local meetings with other professionals, modified work assignments, and other strategies may help clinicians to cope with the distress.45 Formal bereavement counseling that is designed especially for involved clinicians can enhance awareness about vicarious traumatization and encourage adaptive personal and professional coping strategies.

END-OF-LIFE CARE AS A QUALITY-IMPROVEMENT TARGET

Palliative care is now a mainstream matter for quality-improvement agendas in many ICUs. A decade ago, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care End-of-Life Peer Workgroup and 15 associated nurse–physician teams in North America conducted a review of reported practices for end-of-life care and named seven key domains for quality improvement: patient- and family-centered decision making, communication, continuity of care, emotional and practical support, symptom management, spiritual support, and emotional and organizational support for ICU clinicians.46 More than 100 potential interventions were identified as part of this project, directed at patients and their families, clinicians, ICUs, and health care systems. Candidate quality indicators and “bundled indicators” can facilitate measurement and performance feedback in evaluating the quality of palliative care in ICU settings.47

In a multicenter, randomized trial involving critically ill patients who were facing value-related conflicts, ethics consultations helped with conflict resolution and reduced the duration of nonbeneficial treatments that the patients received. 48 In a subsequent cluster-randomized trial involving 2318 patients in which investigators evaluated a five-component, clinician-focused end-of-life strategy,49 there were no significant differences between groups with respect to family satisfaction with care, family or nurse ratings of the quality of dying, time to withdrawal of mechanical ventilation, length of stay in the ICU, or other palliative care indicators.

Favorable assessments of palliative care interventions in the ICU are beginning to emerge. In one study, family members of 126 dying patients in 22 ICUs were randomly assigned to participate in a standard end-of-life family conference or to participate in a proactive family conference and receive a brochure on bereavement.50 The mnemonic “VALUE” framed the five objectives of the proactive family conference: value and appreciate what family members say, acknowledge the family members' emotions, listen to their concerns, understand who the patient was in active life by asking questions, and elicit questions from the family members. Patients whose family members were assigned to the proactive-conference group were treated with significantly fewer nonbeneficial interventions after the family conference than were those whose family members were assigned to the standard-conference group, with no significant between-group difference in the length of stay in the ICU or the hospital. Caregivers in the proactive-conference group, as compared with the standard-conference group, were less negatively affected by the experience and were less likely to have anxiety, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress 90 days after the patients' deaths.

CONCLUSIONS

Palliative care in the ICU has come of age. Its guiding principles are more important than ever in increasingly pluralistic societies. Ensuring that patients are helped to die with dignity begs for reflection, time, and space to create connections that are remembered by survivors long after a patient's death. It calls for humanism from all clinicians in the ICU to promote peace during the final hours or days of a patient's life and to support the bereaved family members. Ensuring death with dignity in the ICU epitomizes the art of medicine and reflects the heart of medicine. It demands the best of us.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢