Erika von Mutius, M.D., and Jeffrey M. Drazen, M.D.

N Engl J Med 2012; 366:827-834

People have suffered from asthma for millennia.1 Although the clinical presentation of asthma has probably changed little, there are many more people who now bear its consequences than there were 200 years ago. As a result of an intense interest in the condition, our understanding of its pathobiology, how to diagnose it, and — most important — how to treat it has evolved dramatically over the past two centuries. To illustrate this change, we provide three fictional reports of consultations performed for essentially the same patient, who has what we in 2012 would refer to as asthma. (A timeline of the major advances in the treatment of asthma from 1812 through 2012 is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.)

The first report is from 1828, the year that the New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery and Collateral Branches of Science joined with the Medical Intelligencer to form the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. The second is from 1928 when the title of the publication was changed to the New England Journal of Medicine, and the third report is from the present.

The three accounts reflect the way in which care was delivered at the time. The first account is in the voice of a general practitioner who was contacted for consultation about a woman with intermittent episodes of dyspnea. The second is in the voice of a generalist who works in a private practice and has an interest in asthma; the patient has been referred to this physician by her own general physician. The third account is in the voice of a sub-subspecialty physician whose practice is limited to the care of patients with asthma. The contemporary patient identified this physician as a specialist in asthma through an Internet search and is consulting him for a second opinion about the appropriateness of her asthma care. She brings to the consultation a detailed history that she wrote, as well as notes from her primary care physician and an allergist.

Our three views of this medical consultation for a patient with asthma are not meant to provide a history of asthma but rather to offer a set of snapshots of the care that the same patient might have received had she sought medical advice in these distinct epochs. There are many diagnostic and therapeutic techniques that we do not mention; this does not mean that they are not important; it simply means that their use does not fit the time frame of our fictitious consultations. Finally, since this article is meant to contribute to the celebration of the Journal's 200th anniversary, we have largely, but not exclusively, used literature from the Journal; our apologies to others who claim primacy.

1828

Office Note on Mrs. A. Smith

I attended at the home of a woman aged 35 years who had just moved with her family to Boston. Her household includes herself and her husband of 17 years, four children, a cook, two maids, a stable boy, and a footman. She sent for me with a complaint of repeated shortness of breath.

The History of Her Illness

When a fit of dyspnea occurs, the patient hears a musical noise in her chest, and she must labor to draw and expel a full breath. When she is stricken, it is her custom to stop all her activities and to inhale the steam coming from the spout of a kettle that her cook keeps always at the ready. With such treatment, she usually recovers within one or two days. Once or twice a year she has a severe fit, which may last for a week, and she is confined to her sick bed.

She has suffered such fits of laborious breathing since her childhood. They occur at any time of the year but are more common in the spring, when the trees bloom, and in the late summer than at other times. In the winter she reports that it is common for her to be so stricken when she walks from the harbor to her home, a distance of nearly a mile along a path that ascends steeply. This difficulty of respiration has become such a frequent occurrence that she now routinely calls for her coach even for very short journeys outside her home. During each of her periods of confinement for childbearing, the fits were far less numerous and severe in character, but within a few months after she had given birth, they returned.

Often, even when she is not suffering from laborious breathing, she will arise in the dark of the night and stand at the open window, gasping for air. By the time that dawn arrives she has usually regained control of her breathing and returns to sleep.

Her difficulty of respiration is accompanied by itchy eyes and a runny nose. She has a cough with these fits, but she does not produce phlegm. She does not have hemoptysis. No one among her family or close acquaintances has died from consumption. Her weight has been stable, and when she is not suffering from laborious breathing, her strength is good. She has not had rheumatic fever.

Her mother, now deceased, also suffered from difficulty of respiration; her father did not. Of her four children, ages 14, 12, 9, and 7, her two eldest, both boys, have suffered from the same symptoms, although her oldest son has not had a fit of laborious breathing for more than a year.

My Examination

Observation of her breathing on the occasion of my consultation revealed nothing far out of the ordinary. Her speech was full and normal. The movements of her chest were full. I could palpate nothing abnormal in her heart motion. There was no swelling of her liver or her legs. I used a newly acquired stethoscope to examine her chest. Although the patient could not hear the musical sounds that have been termed “wheezes,” I was able to hear them.

My Opinion

The patient clearly suffers from an asthma; she may also have what has been described as “hay fever” in the spring and fall.2 I believe her fits of laborious breathing are similar to the asthmatic fits that Sir John Floyer suffered from and described in his “Treatise of the Asthma.”3 He describes this type of asthma as follows: “[T]he expiration is very slow and leisurely and wheezing, and the asthmatic can neither cough, sneeze, spit nor speak freely; and in the asthmatic fit, the muscular fibres of the bronchia and vesiculae of the lungs are contracted, and that produces the wheezing noise which is most often observable in expiration.” I have no concern that she suffers from consumption or from conditions of the heart that may lead to dropsy.

I think that she may benefit from smoking the leaf of Datura stramonium, also known as the thorn-apple plant. Many asthma sufferers have tried this remedy, and it seems to provide relief from a fit, even though it will not prevent a recurrence. Several years ago, Dr. Bree reported in the New England Journal of Medicine and Surgery that such smoking had a deleterious effect on a number of patients suffering from difficulty of respiration.4 However, in my experience, patients such as this woman will derive benefit from such treatment in that it shortens the duration of their indisposition from an asthmatic fit. I recommended this treatment to my patient, and she tells me that she has benefited from it.

Comment: In the early 1800s, there were many “asthmas,” since this was the term for any episodic shortness of breath. The physician needed to be sure that the primary cause was not tuberculosis or cardiac disease (e.g., mitral stenosis); both were very common at the time. Once a diagnosis of asthma (as we know it now) was established, the number of effective treatments was quite limited; inhalation of smoke from burning Datura stramonium was probably the best. This agent had anticholinergic properties and was the forerunner of the currently used antimuscarinic agents, such as ipratropium and tiotropium.5 There were numerous other treatments, such as inhalation of the fumes of hydrocyanic acid6 or inflation of the lungs with a bellows.7 Fortunately, such treatments and many others that produced no benefit and probably caused harm are no longer used.

1928

Letter Regarding Mrs. A. Smith

Dear Dr. Jones,

Thank you for referring your patient, Mrs. A. Smith, for evaluation concerning a possible diagnosis of asthma. I found the patient's history, as recounted in your office notes, to be complete and accurate.

History

The critical feature of her case is that Mrs. Smith, age 35, has been having “asthma attacks” since her early childhood. Her attacks are characterized by the relatively sudden onset of dyspnea; they are more frequent in the spring and fall, when they are often preceded by symptoms of rhino-conjunctivitis. If untreated, an attack will last for a few days, but if she is treated with a subcutaneous injection of adrenaline, as you have administered at your office, she often has relief from acute symptoms, and the attack may or may not recur. Recently, her attacks have been more frequent, and she does not feel that her breathing is improved to the point where she can carry out her responsibilities as a wife and mother.

Her mother carried a diagnosis of asthma, as do two of her children. She is currently not using any medications.

Physical Examination

Her physical examination, at a time when she was not having acute asthmatic symptoms, showed normal body temperature, blood pressure, and pulse. She had no rashes. Her nasal passages were closely examined and showed inflammation and edema but no polyps. Her respirations were 24 and slightly labored. She had diminished tactile fremitus. Expiratory wheezing of modest profusion was audible in all lung fields. Her cardiac examination was normal. There was no clubbing, cyanosis, or edema.

Laboratory Studies

I examined the radiograph of the chest that she brought with her, which was taken within the last month. It showed hyperinflation of the lungs, but there were no abnormal shadows; there were no findings that would suggest tuberculosis. Her cardiac silhouette did not show any abnormalities.

A blood smear was made, showing 14 per cent eosinophils; in a normal person this is most often less than 5 per cent. A sputum sample was also examined, and all the polymorphonuclear leukocytes observed were eosinophils. Specialized skin testing was performed. She had positive reactions to extracts of ragweed and horse dander.

My Opinion

Your diagnosis of asthma is correct. The episodes are characteristic, and there is no other likely cause suggested by her medical history or the physical examination and laboratory findings. In fact, the presence of eosinophils in the blood and sputum makes the diagnosis virtually certain. The positive skin tests make this case one of extrinsic asthma. Hypersensitivity to proteins is the likely physiological basis of asthma, although the exact mechanisms leading to sensitization are not clear.

Treatment is difficult. Your use of adrenaline injections for acute attacks is appropriate8; there is reason to believe that treatment with oral ephedrine may also help with her asthmatic episodes.9The relief is of longer duration than with injected adrenaline and the patient can administer it herself. Ephedrine is not a substitute for injections of adrenaline when the patient is in extremis.

The critical factor in treatment is removing the patient from exposure to the proteins to which she is sensitive. Her positive skin test to ragweed pollen extract is in agreement with the clinical history of worsening disease in the autumn. However, there may be proteins to which she is allergic that were not included in our skin test panel. In my experience, removing a protein from a patient's exposure is very hard to accomplish. One strategy, which I am loath to suggest unless there is no other hope, is a move to a climate where there are fewer proteins in the air to which the patient would be exposed.10

Comment: By 1928, the differential diagnosis of asthma was well established, and diagnostic techniques were available that made it possible to be reasonably certain that patients did not have heart disease or pneumonia when they were labeled as asthmatic.11 Physicians of the time often used the term “asthma” to refer to episodic dyspnea, but qualifiers such as “cardiac” were used. By 1928, eosinophils in the blood and sputum were known to be characteristic of asthma.12 Skin tests for allergies had been developed and were used clinically to help clinicians identify specific offending environmental proteins. The issues that plague us today — allergies to multiple allergens and difficulty in interpreting skin tests — were of concern to physicians in 1928.

There was not much available in the way of treatment. Ephedrine, an orally active sympathomimetic agent, had been discovered in China9 and used in asthma treatment, but other than allergen removal and adrenaline injections, there was little to offer patients with asthma beyond advising them to smoke “asthma cigarettes” (made from the leaves of D. stramonium [Figure 1]

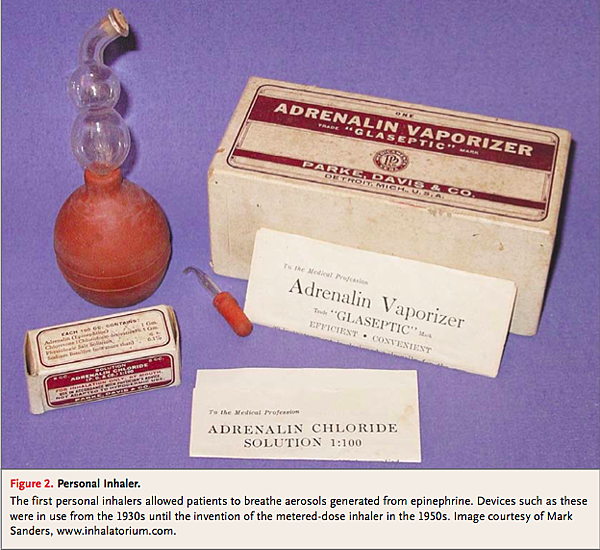

Theophylline was available but was used as a diuretic; its value in the treatment of asthma had not yet been discovered. Aerosol inhalation therapy had not been widely adopted by 1928, but by the 1940s an inhaled formulation of epinephrine was marketed for asthma treatment (Figure 2

2012

E-Mail Message to Ms. Smith

Dear Ms. Smith,

Thank you for asking me to provide you with a direct personal consultation concerning your asthma and your asthma care. I will summarize the salient facts from the detailed written history and physician's note you kindly provided.

As pointed out in your written history, you have had asthma since childhood. Among your earliest recollections is receiving injection treatments and later inhalation treatments for asthma in an emergency room. In your early teenage years you started treatment with inhaled Vanceril (beclomethasone), two puffs twice a day; 10 years ago, you switched to inhaled Qvar (beclomethasone driven by a hydrofluoroalkane [an ozone-layer–friendly] propellant), and Singulair (montelukast) was added to your regimen. Over the past 10 years, you have tried two different “combination inhalers,” containing both inhaled glucocorticoids and long-acting β2-agonists — namely, Advair (fluticasone propionate and salmeterol) and Symbicort (budesonide and formoterol fumarate dehydrate). These medications did not improve your symptoms or lung function as compared with inhaled beclomethasone alone, and you switched backed to Qvar.

Even with this regimen, however, your asthma symptoms are still present and bothersome. For example, two to three times a month you are awakened from your sleep between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. by shortness of breath and cough; you can hear yourself wheeze. If you use your rescue albuterol inhaler, you are usually able to get back to sleep by 5 a.m.

Two years ago, skin tests were performed, and your total IgE level was measured. Your only positive skin tests were for house-dust mites and ragweed. Your total IgE level was 75 IU per milliliter. The allergist who did the testing suggested that you add a nonsedating antihistamine, such as loratadine, to your treatment during the times of year when you are most susceptible to symptoms; the loratadine was of some small help in controlling your runny nose, but there was no change in your asthma symptoms. Your allergist also referred you to a gastroenterologist, who performed 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring and found no abnormalities.

In the past decade, you have required treatment with oral prednisone on three occasions; the last instance was in 2009. Each of these exacerbations occurred during your allergy season. You have a peak-flow meter, which you use occasionally. Your best reading is 500 liters per minute; on most days, your peak-flow values are between 350 and 400 liters per minute.

You work in an office. You live with your husband and two children in a single-family home heated and air-conditioned with forced air. You have taken extensive measures to remove allergens from your home, including having the air ducts cleaned and tested for allergens. You have no pets. You have never smoked, and the same is true for your husband and your children. Smoking has not been allowed in your workplace for more than a decade. Your mother had asthma.

Your current medications are Qvar, 80 μg per puff, two puffs twice a day; Singulair, 10 mg per day, taken at night; and one multivitamin per day.

You would like a single consultation and confidential second opinion as to how your asthma has been managed and how to improve your asthma control.

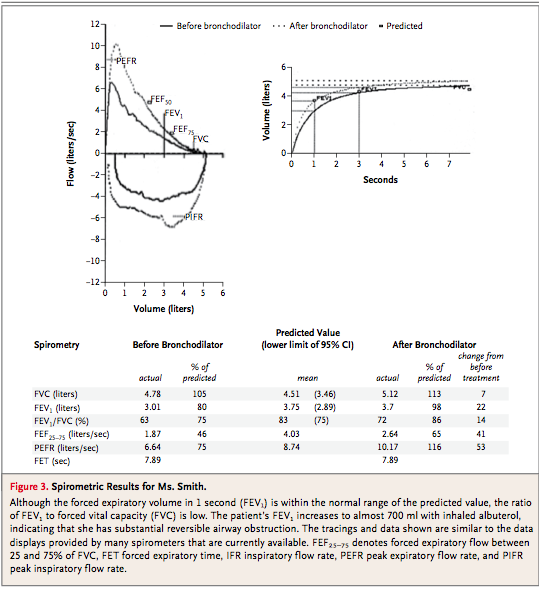

On physical examination today, you looked well. Your weight was 135 lb [61.2 kg]. Your blood pressure was 110/75 mm Hg, and your pulse was 77 beats per minute according to the pulse oximeter, which also indicated that your hemoglobin saturation while you were breathing ambient air was 95%. Your physical examination was largely normal. No abnormalities were noted in your eyes, nose, or ears. Your chest examination was normal except for the presence of scattered expiratory wheezes, which were heard best during rapid, shallow breathing. There were no abnormalities in your extremities. Your neurologic examination was normal as well. Lung-function testing was performed in our laboratory; the results are attached to this letter (Figure 3

I think that the diagnosis of asthma is well established. You have a long history of asthma and have had salutary symptomatic responses to asthma treatments, your lung-function tests still show reversibility of airway obstruction of more than 15% with albuterol, and no other competing diagnosis has emerged over many years. The major issue now is to determine whether there are additional treatments that could help suppress your asthmatic symptoms without increasing the treatment burden.

You and your physicians have done an excellent job of managing your asthma. The treatments you are using now are well established and known to be effective. There are three treatments that could be added to your regimen, but it is difficult to be certain that they would be effective. First, oral theophylline could be added to your regimen. Although you cannot recall having received treatment with theophylline, given your age and asthma history, it is likely that you were treated with this agent as a child. This therapy could be of value, but it is necessary to monitor blood levels of the drug to obtain an optimum response, and some patients find testing to be burdensome. There is a small chance that theophylline could make your asthma worse by relaxing the muscle that separates your stomach from your esophagus; if this occurred, the treatment would be stopped.

Second, Singulair could be replaced with Zyflo CR (zileuton, controlled release). The active ingredient in Singulair is montelukast, which blocks the action of the cysteinyl leukotrienes at the CysLT1 receptor, whereas zileuton prevents the synthesis of both cysteinyl leukotrienes and dihydroxy leukotrienes. There are theoretical reasons to believe that controlled-release zileuton would yield a clinical benefit, but there are no compelling data to support this approach. Monitoring of liver function is required during initiation of treatment with zileuton.

Third, Xolair (omalizumab) could be added to your regimen. This anti-IgE monoclonal antibody is given once a month by injection. There is clearly an allergic component of your disease; your total IgE level is elevated, but it is not so high as to preclude the use of omalizumab.

As we discussed, I think your primary care physician has done an excellent job in designing your asthma treatment. You should discuss our consultation with her and decide what is in your best interest.

Comment: There have been three major changes in our understanding of asthma between 1928 and 2012. First, spirometry, which had been invented in the 1840s,13 was refined by adding time to volume output, and between the late 1940s and early 1950s, measurements made from forced exhalations were used in the diagnosis and treatment of asthma.14 Other lung-function tests were developed and used, and the relationships between clinical physiology and symptoms were delineated.15 Second, glucocorticoids were identified as an effective and useful asthma treatment. They were first used systemically in the early 1950s16 and were subsequently made available in inhaled form17,18,; these agents remain the standard of care today. Third, our understanding of the immunobiology of asthma progressed beyond the view that the essential mechanism was an immediate hypersensitivity reaction.19,20, Unfortunately, these advances in understanding the cell biology of asthma have not yet been translated into new therapies, although new therapies have been derived from our improved understanding of immediate hypersensitivity responses — notably, the use of leukotriene modifiers21 and anti-IgE antibodies.22

Our patient is current in her medical knowledge and is using medical information widely available on the Internet to help in the management of her chronic condition. The consultant used measures of lung function to quantify her physiological deficit. The consultant also measured the patient's IgE level, which was consistent with allergic asthma, and provided the information needed for anti-IgE treatment, should the patient elect this approach. The patient has used all the standard asthma therapies but has residual symptoms. The consultant outlines other asthma treatments that the patient could try, highlighting the need to try different treatments to see whether one or another will work. Sadly, we still do not have a way to predict a given patient's response to therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

These three case histories illustrate that asthma as a disease has not changed for two centuries. We have made real progress in identifying patients with asthma and in understanding its biologic basis and its treatment. Progress has also been made in diagnostic testing, which has been refined to measure lung function with great accuracy and repeatability. In addition, we can measure the lung's responsiveness to triggering agents and thereby obtain objective indications of disease activity, in addition to the patient's history. We have come to realize that allergic responses often substantially contribute to both chronic persistent asthma and acute exacerbations of asthma symptoms, although this association may have been overemphasized. The current focus is on immune responses in affected patients; we believe that airway inflammation plays a critical role in asthma, but the precise nature of that inflammation remains a mystery. The knowledge that asthma runs in families has become the basis for very sophisticated studies of the genetics of asthma, but not much of its heritability can be explained by all the genes identified to date. In spite of all the progress achieved over the past two centuries, we still do not understand the fundamental causes of asthma. Hence, we do not have therapies that address the underlying mechanisms; we have no cure for asthma. The medications at hand provide relief of symptoms and improve lung function and airway responsiveness, but they do not prevent exacerbations or progression of disease, and the most desirable accomplishment, the primary prevention of asthma, is a vision that has not yet become a reality.

最後,他有一張互動式的圖片,我把它直接拼起來給各位看看:

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢