More than 29 million people in the United States and 420 million globally have diabetes, with a projected global prevalence of 642 million by 2040.1,2

This accelerating pandemic comes with high personal and financial costs to the individual, society, and the economy. The expanding number of antihyperglycemic medication options for type 2 diabetes, often involving different mechanisms of action and safety profiles, can be a challenge for clinicians, and the increasing complexity of diabetes management requires a well-informed strategy for prevention and treatment of this disease.

In this Viewpoint, we highlight the importance of patient-centered goals for glucose-lowering therapy, the essential role of lifestyle modification, the mechanisms of action of current therapeutic options and their risks and benefits, and briefly comment on the recent cardiovascular outcomes trials mandated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Patient-Centered Goals

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) have proposed a set of patient and disease characteristics that have utility in guiding a patient-centered approach for the management of type 2 diabetes.3 Some patient characteristics support more and others support less aggressive glucose control. Specifically, tight glucose control (hemoglobin A1c level <7.0%) is recommended for a newly diagnosed patient with diabetes but without disease complications and with a long life expectancy. For patients with long-standing diabetes, short life expectancy, severe diabetes–related complications, comorbidities, or the inability to safely implement and follow an intensive regimen, the goal is to develop a simple strategy focused on safety and avoidance of hypoglycemia. Establishing and discussing the goals of therapy with patients are important.

Behavior Change and Use of Team Support

All strategies to improve blood glucose control will involve patient engagement in diabetes self-management and lifestyle change. Formal diabetes education about diet, physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, pharmacotherapy-related issues, and screening for complications is imperative both at the outset and at regular follow-up intervals.4 Most health care systems have dietitians and certified diabetes educators for such patient support. These resources are underused. These support services complement and augment the primary care clinician’s role in endorsing the importance of lifestyle behaviors at each visit.

Most patients with diabetes will need to move from lifestyle management alone to lifestyle management combined with pharmacological therapy to reach glycemic targets. It is important to communicate the progressive nature of the disease process to patients so they do not perceive that their lifestyle “failed” or that they are at fault. Patients with diabetes also require attention to microvascular risks, cholesterol and blood pressure management, and assessment of depression.

Pharmacological Management

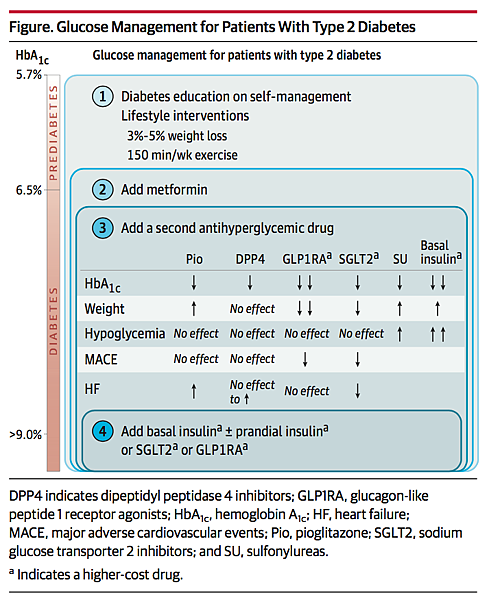

All FDA-approved medications for treating hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes lower hemoglobin A1c levels by 0.6% to 1.5%. The guidelines published by different associations are not entirely consistent, but they agree on a set of principles including (1) set a glycemia or hemoglobin A1c goal; (2) start with metformin in most patients; (3) use combination therapy to achieve the glycemic goals; (4) avoid hypoglycemia; and (5) understand medication adverse effect profiles (Figure). The use of metformin as first-line therapy is based on its glucose-lowering efficacy, safety profile, weight neutrality, and reasonable cost. Metformin therapy should be titrated to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects. One small cardiovascular outcomes trial and cohort data also suggest cardioprotection with metformin.5

Combination Therapy

The guidelines from the ADA and EASD indicate that any FDA-approved second agent can be used in combination with metformin, whereas the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends either incretin-based therapy or sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibition agents.3,6 Importantly, clinicians should not wait until the patient’s glycemic control deteriorates before adding a second agent.

Historically, insufficient insulin secretion was treated with either the insulin secretagogue sulfonylureas (currently glibenclamide or glipizide) or insulin replacement therapy. Both have good glucose-lowering efficacy, and confer risk for hypoglycemia and weight gain. Pioglitazone, an additional effective option, is not one of the medications recommended by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, possibly due to concern about an increased risk of heart failure and weight gain.

Incretin-Based Therapies

Incretin-based therapies augment glucose-dependent insulin secretion and confer a low risk of hypoglycemia. These agents include injectable glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP1RA) and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors. Glucagon-like peptide 1 is a hormone secreted by the distal small intestine in response to food ingestion. It augments glucose-dependent insulin secretion, decreases islet glucagon secretion, slows gastric emptying, and increases satiety. Glucagon-like peptide 1 is rapidly degraded by the enzyme DPP4. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors maintain endogenous GLP1 concentrations, modestly lower blood glucose, are weight neutral, and do not cause hypoglycemia.

Injectable GLP1RA increases GLP1 to pharmacological levels, robustly lowers blood glucose level, and facilitates weight loss without a risk for hypoglycemia (except when used with insulin or sulfonylureas). Glucagon-like peptide 1 can be associated with transient nausea and vomiting (lasting 1-3 months). It is essential to communicate with the patient about the risk of nausea prior to titration with GLP1RA agents and, if needed, treat the gastrointestinal adverse effects to improve adherence. Recently published trials on cardiovascular outcomes demonstrate a cardiovascular benefit of 2 agents in this class: liraglutide7 and semaglutide.8

Sodium Glucose Transporter 2

Sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitors decrease renal reabsorption of glucose in the proximal tubule by blocking the sodium glucose transporter 2, leading to glycosuria. These agents effectively lower hemoglobin A1c level without causing hypoglycemia. Potential adverse effects include polyuria, diuresis, blood pressure lowering, weight loss, ketoacidosis, and increased genital infections. These agents, however, do not increase the risk of urinary tract infections. The empagliflozin cardiovascular outcomes trial demonstrated a significant decrease in all-cause mortality and heart failure9 and the FDA recently recommended approval for a cardiovascular indication.

Effective Use of Insulin

A patient with hemoglobin A1c level greater than 9% (goal of <7%) taking metformin and noninsulin medications will require insulin therapy.3,6 Patient- or clinician-guided titration of basal insulin to fasting blood glucose goals is safe and effective. A common strategy is to start with a low dose of long-acting insulin at bedtime (approximately 10 units) and titrate to a fasting blood glucose level of less than 120 mg/dL. This starting dose will not cause hypoglycemia, but insulin titration is crucial (30-50 units usually will be needed).

Basal insulin can be added to any regimen. It is safe and effective to combine basal insulin with metformin, GLP1RA, SGLT2, or pioglitazone to achieve glucose control. Two formulations of single-injection therapy combining long-acting insulin and GLP1 were recently approved by the FDA. This combination demonstrates excellent glucose-lowering effects, weight neutrality or weight loss, and minimal cases of hypoglycemia. Consideration of efficacy, adverse effects, and cost of each medication is necessary to improve adherence and outcomes.

Summary

Patient-centered diabetes management can be accomplished with lifestyle modification and combination therapy. Metformin is an optimal first-line agent; newer GLP1 and SGLT2 agents have efficacy for glucose lowering coupled with weight loss and potential cardiovascular risk reduction; and insulin therapy is generally safe and effective for patients not controlled with noninsulin agents. In younger, healthy, newly diagnosed patients, a hemoglobin A1c level less than 7% should be the goal; in older individuals with comorbidities, less stringent goals with a focus on safety and avoidance of hypoglycemia are critical. Antihyperglycemic therapy should be combined with evidence-based treatment of cholesterol and blood pressure for cardiovascular risk reduction. Although the cardiovascular benefits of SGLT2 and GLP1 agents merit consideration, these medications are not replacements for statin therapy or blood pressure management for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Back to top

Article Information

Corresponding Author: JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 900 Commonwealth Ave, Third Floor, Boston, MA 02215 (jmanson@rics.bwh.harvard.edu).

Published Online: March 1, 2017. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0241

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Reusch reported receiving grant funding from AstraZeneca and Merck; and serving on the board of directors for the American Diabetes Association. No other disclosures were reported.

References

1.

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/2014statisticsreport.html. Accessed January 4, 2017.

2.

American Diabetes Association. Diabetes statistics. http://www.diabetes.org. Accessed January 4, 2017.

3.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):140-149.PubMedArticle

4.

Sherr D, Lipman RD. The diabetes educator and the diabetes self-management education engagement. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(5):616-624.PubMedArticle

5.

Holden SE, Jenkins-Jones S, Currie CJ. Association between insulin monotherapy versus insulin plus metformin and the risk of all-cause mortality and other serious outcomes. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153594.PubMedArticle

6.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2016 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(1):84-113.PubMedArticle

7.

Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322.PubMedArticle

8.

Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-1844.PubMedArticle

9.

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-2128.PubMedArticle

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢