Stephen C. Lazarus, M.D.

N Engl J Med 2010; 363:755-764August 19, 2010

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the author's clinical recommendations.

A 46-year-old woman who has had two admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU) for asthma during the past year presents with a 4-day history of upper respiratory illness and a 6-hour history of shortness of breath and wheezing. An inhaled corticosteroid has been prescribed, but she takes it only when she has symptoms, which is rarely. She generally uses albuterol twice per day but has increased its use to six to eight times per day for the past 3 days. How should this case be managed in the emergency department?

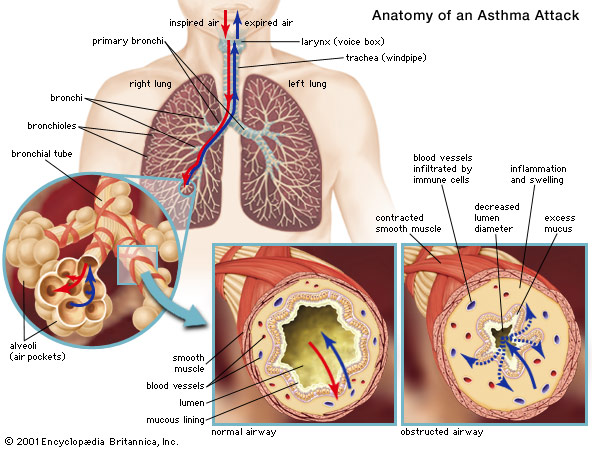

The Clinical Problem

Asthma is one of the most common diseases in developed countries and has a worldwide prevalence of 7 to 10%.1 It is also a common reason for urgent care and emergency department visits. From 2001 through 2003 in the United States, asthma accounted for an average 4210 deaths annually and an average annual total of approximately 504,000 hospitalizations and 1.8 million emergency department visits.2 The average annual rate of emergency department visits for asthma was 8.8 per 100 persons with current asthma. Rates were higher among children than among adults (11.2 vs. 7.8 visits per 100 persons), among blacks than among whites (21 vs. 7 visits per 100 persons), and among Hispanics than among non-Hispanics (12.4 vs. 8.4 visits per 100 persons). Women made twice the number of emergency department visits as men.2 Approximately 10% of visits result in hospitalization.1

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, with varied triggers, manifestations, and responsiveness to treatment. Some patients with acute severe asthma presenting to the emergency department have asthma that responds rapidly to aggressive therapy, and they can be discharged quickly; others require admission to the hospital for more prolonged treatment. The reasons for this difference in responsiveness to treatment include the degree of airway inflammation, presence or absence of mucus plugging, and individual responsiveness to β2-adrenergic and corticosteroid medications. The major challenge in the emergency department is determining which patients can be discharged quickly and which need to be hospitalized.

Strategies and Evidence

Initial Assessment in the Emergency Department

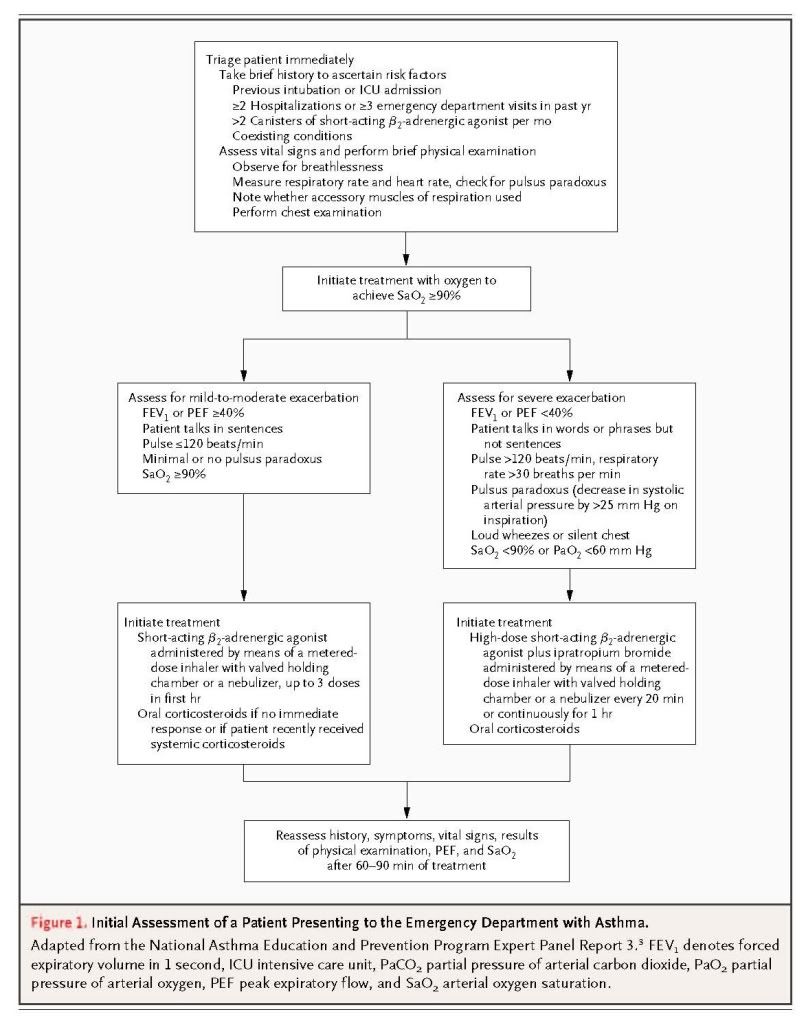

Patients presenting to the emergency department with asthma should be evaluated and triaged

quickly to assess the severity of the exacerbation and the need for urgent intervention (Figure 1 Initial Assessment of a Patient Presenting to the Emergency Department with Asthma.).

A brief history should be obtained, and a limited physical examination performed. This assessment should not delay treatment; it can be performed while patients receive initial treatment. Clinicians should search for signs of life-threatening asthma (e.g., altered mental status, paradoxical chest or abdominal movement, or absence of wheezing), which necessitate admission. Attention should be paid to factors that are associated with an increased risk of death from asthma, such as previous intubation or admission to an ICU, two or more hospitalizations for asthma during the past year, low socioeconomic status, and various coexisting illnesses.3 The measurement of lung function (e.g., forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] or peak expiratory flow [PEF]) can be helpful for assessing the severity of an exacerbation and the response to treatment but should not delay the initiation of treatment. Laboratory and imaging studies should be performed selectively, to assess patients for impending respiratory failure (e.g., by measuring the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide [PaCO2]), suspected pneumonia (e.g., by obtaining a complete blood count or a chest radiograph), or certain coexisting conditions such as heart disease (e.g., by obtaining an electrocardiogram).

Treatment in the Emergency Department

All patients should be treated initially with supplementary oxygen to achieve an arterial oxygen saturation of 90% or greater, inhaled short-acting β2-adrenergic agonists, and systemic corticosteroids (Figure 1). The dose and timing of these agents and the use of additional pharmacologic therapy depend on the severity of the exacerbation.

β2-Adrenergic Agonists

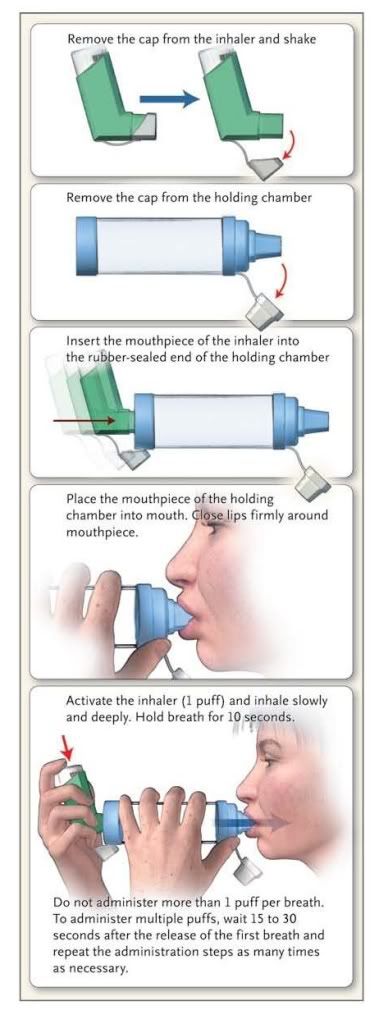

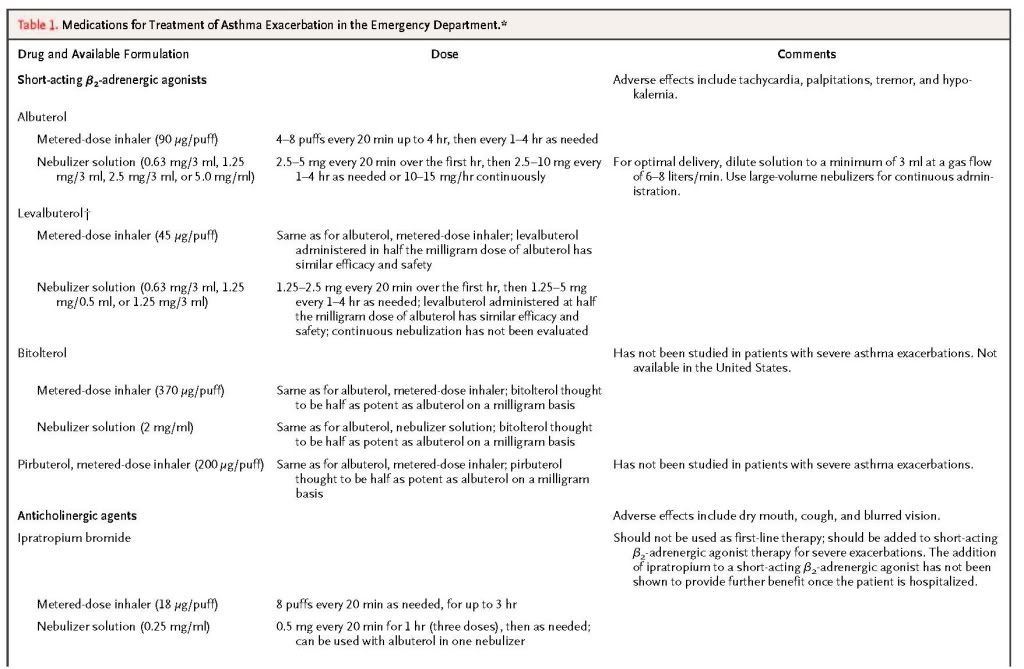

Inhaled short-acting β2-adrenergic agonists should be administered immediately on presentation, and administration can be repeated up to three times within the first hour after presentation. The use of a metered-dose inhaler with a valved holding chamber is as effective as the use of a pressurized nebulizer in randomized trials,4,5 but proper technique is often difficult to ensure in ill patients. Most guidelines recommend the use of nebulizers for patients with severe exacerbations; metered-dose inhalers with holding chambers can be used for patients with mild-to-moderate exacerbations, ideally with supervision from trained respiratory therapists or nursing personnel (see the Supplementary Appendix and a Video, both available at NEJM.org, for descriptions of how to use inhalers with and inhalers without a holding chamber, respectively).

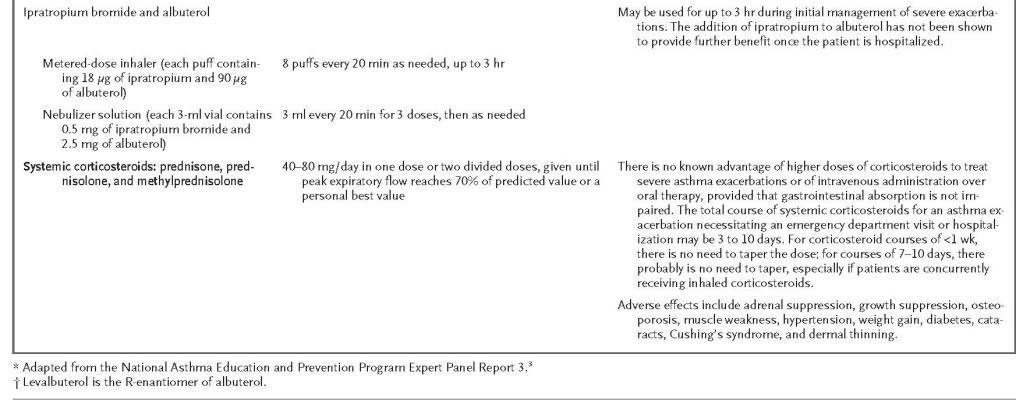

The dose administered by means of metered-dose inhalers for exacerbations is substantially greater than that used for routine relief: four to eight puffs of albuterol can be administered every 20 minutes for up to 4 hours and then every 1 to 4 hours as needed (Table 1 Medications for Treatment of Asthma Exacerbation in the Emergency Department.).

Albuterol can be delivered by means of a nebulizer either intermittently or continuously. A meta-analysis of results from six randomized trials indicated that intermittent administration and continuous administration have similar effects on both lung function and the overall rate of hospitalization,6 whereas a Cochrane review of findings from eight trials suggested that continuous administration resulted in greater improvement in PEF and FEV1 and a greater reduction in hospital admissions, particularly among patients with severe asthma. 7

Albuterol is the inhaled β2-adrenergic agonist most widely used for emergency management. Levalbuterol, the R-enantiomer of albuterol, has been shown to be effective at half the dose of albuterol, but randomized trials conducted in the emergency department have not consistently shown a clinical advantage of levalbuterol over racemic albuterol.8,9 Pirbuterol and bitolterol are effective for mild or moderate exacerbations, but a higher dose is required than with albuterol or levalbuterol, and their use for severe exacerbations has not been studied.

Oral or parenteral administration of β2-adrenergic agonists is not recommended, since neither has been shown to be more effective than inhaled β2-adrenergic agonists, and both are associated with an increased frequency of side effects. The long-acting inhaled β2-adrenergic salmeterol has not been studied for the treatment of exacerbations, though trials with formoterol (ClinicalTrials.gov numbers, NCT00819637 and NCT00900874) are under way.

Anticholinergic Agents

Because of its relatively slow onset of action, inhaled ipratropium is not recommended as monotherapy in the emergency department but can be added to a short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist for a greater and longer-lasting bronchodilator effect.10,11 In patients with severe airflow obstruction, the use of ipratropium together with a β2-adrenergic agonist in the emergency department, as compared with a β2-adrenergic agonist alone, has been shown to reduce rates of hospitalization by approximately 25%,12,13 although there is no apparent benefit of continuing ipratropium after hospitalization.

Systemic Corticosteroids

In most patients with exacerbations that necessitate treatment in the emergency department, systemic corticosteroids are warranted. The exception is the patient who has a rapid response to initial therapy with an inhaled β2-adrenergic agonist. Although most randomized, controlled trials of corticosteroids in patients seen in the emergency department and those admitted to the hospital have been small, these studies individually14,15 and collectively16-18 show that the use, as compared with nonuse, of systemic corticosteroids is associated with a more rapid improvement in lung function, fewer hospitalizations, and a lower rate of relapse after discharge from the emergency department. Because comparisons of oral prednisone and intravenous corticosteroids have not shown differences in the rate of improvement of lung function or in the length of the hospital stay,19-21 the oral route is preferred for patients with normal mental status and without conditions expected to interfere with gastrointestinal absorption. Although the optimal dose of corticosteroid is not known, pooled data from controlled trials involving patients seen in the emergency department or admitted to the hospital have shown no significant advantage of doses greater than 100 mg per day of prednisone equivalent.19,20,22-25 The most recent guidelines from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) (Expert Panel Report 3) recommend the use of 40 to 80 mg per day in one dose or two divided doses. 3

Inhaled Corticosteroids

Although high-dose inhaled corticosteroids are often used to treat worsening of asthma control and to try to prevent exacerbations, the evidence does not support the use of inhaled corticosteroids as a substitute for systemic corticosteroids in the emergency department.26 Inhaled corticosteroids are, however, preferred for long-term asthma control. At the time of discharge from the emergency department, these agents should be continued in patients who have been taking them for long-term control and should be prescribed for patients who have not previously taken them. In a randomized, controlled trial of 1006 consecutively enrolled patients with acute asthma treated in a Canadian emergency department, the addition at discharge of inhaled budesonide (for 21 days) to treatment with oral corticosteroids (for 5 to 10 days) was associated with a 48% reduction in the rate of relapse at 21 days and with improvement in the quality of life with respect to asthma (as measured by the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire) and symptoms, as compared with treatment with oral corticosteroids alone.27

Treatments That Are Not Recommended

Although methylxanthines were once a standard treatment for asthma in the emergency department, it is now clear that their use increases the risk of adverse events without improving outcomes.28 Antibiotics should not be used routinely but rather should be reserved for patients in whom bacterial infection (e.g., pneumonia or sinusitis) seems likely. Similarly, neither aggressive hydration nor administration of mucolytic agents is recommended for acute exacerbations.3

Assessment of Response to Treatment

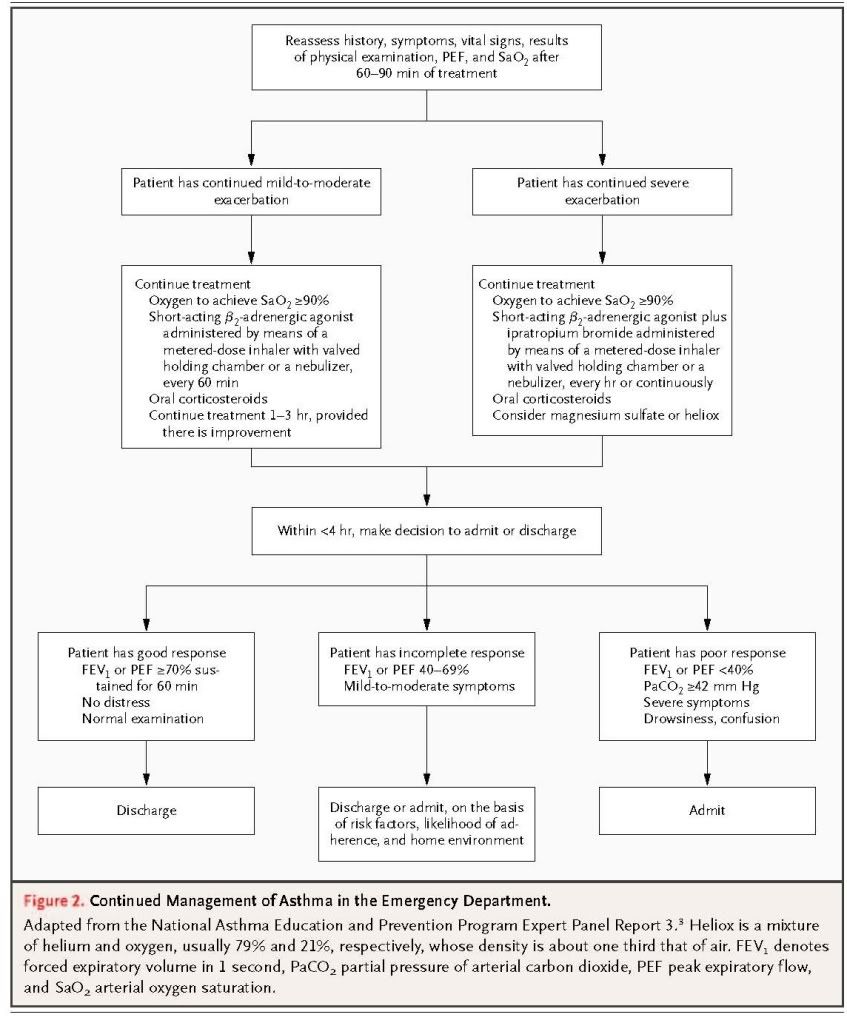

Patients should be reassessed after the first treatment with an inhaled bronchodilator and again at 60 to 90 minutes (i.e., after three treatments).3 This assessment should include a survey of symptoms, a physical examination, and measurement of FEV1 or PEF (Figure 2 Continued Management of Asthma in the Emergency Department.).

For the most severe exacerbations, this repeat assessment should probably include the measurement of arterial blood gases. Most patients will have clinically significant improvement after one dose of an inhaled bronchodilator, and 60 to 70% will meet the criteria for discharge from the emergency department (see below) after three doses.29-31 The degree of subjective and objective improvement that occurs in response to treatment predicts the need for hospitalization.32-38 In a study of 720 patients treated in 36 Australian emergency departments, the need for hospital admission among patients assessed as having moderate asthma, as well as the need for ICU care of patients assessed as having severe asthma, was better predicted by the assessment of asthma severity after 1 hour of treatment than by the initial assessment in the emergency department.38

Indications for Admission

After treatment in the emergency department for 1 to 3 hours, patients who have an incomplete or poor response, defined as an FEV1 or PEF of less than 70% of the personal best or predicted value, should be evaluated for admission to the hospital. Patients who have an FEV1 of less than 40%, persistent moderate-to-severe symptoms, drowsiness, confusion, or a PaCO2 of 42 mm Hg or greater should be admitted. Patients who have an FEV1 of 40 to 69% and mild symptoms should be assessed individually for risk factors for death, ability to adhere to a prescribed regimen, and the presence of asthma triggers in the home. The NAEPP Expert Panel Report 3 suggests that the decision to admit or discharge a patient should be made within 4 hours after presentation to the emergency department.3

Management of Respiratory Insufficiency

Patients with altered mental status, exhaustion, or hypercapnia should be considered for immediate intubation and ventilatory support. Because of high positive intrathoracic pressures, intubation and ventilation may lead to hypotension and barotrauma. Care should be taken to ensure adequate intravascular volume, and to avoid high airway pressures. A strategy of “permissive hypercapnia,” achieved by adjusting the ventilator to correct hypoxemia while avoiding high airway pressures, was associated in an observational study with decreased mortality among patients with status asthmaticus,39 and this approach has become standard.

Guidelines suggest that once a decision has been made in the emergency department to intubate a patient, the procedure should be semielective and performed under controlled conditions (vs. performed as an emergency procedure by the first available staff). Randomized trials have shown a benefit from noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but most information used to guide the ventilation strategy for treating acute asthma comes from case reports or noncontrolled studies. A randomized crossover study that compared the use of bilevel positive airway pressure for 2 hours with standard care in children with acute asthma showed a significantly lower respiratory rate and improved scores on a questionnaire regarding asthma symptoms with bilevel positive airway pressure but no significant difference in arterial oxygen saturation, transcutaneous carbon dioxide levels, or other outcomes.40 In a randomized, sham-controlled trial of the use of bilevel positive airway pressure in 30 adults with acute asthma, bilevel positive airway pressure was associated with a higher FEV1 value at 4 hours and a lower rate of hospitalization (17.6%, vs. 62.5% with sham treatment).41 These data suggest that noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation could be considered for patients who decline intubation and for selected patients who are likely to cooperate with mask therapy, but more data are needed to recommend this approach.

Discharge from the Emergency Department

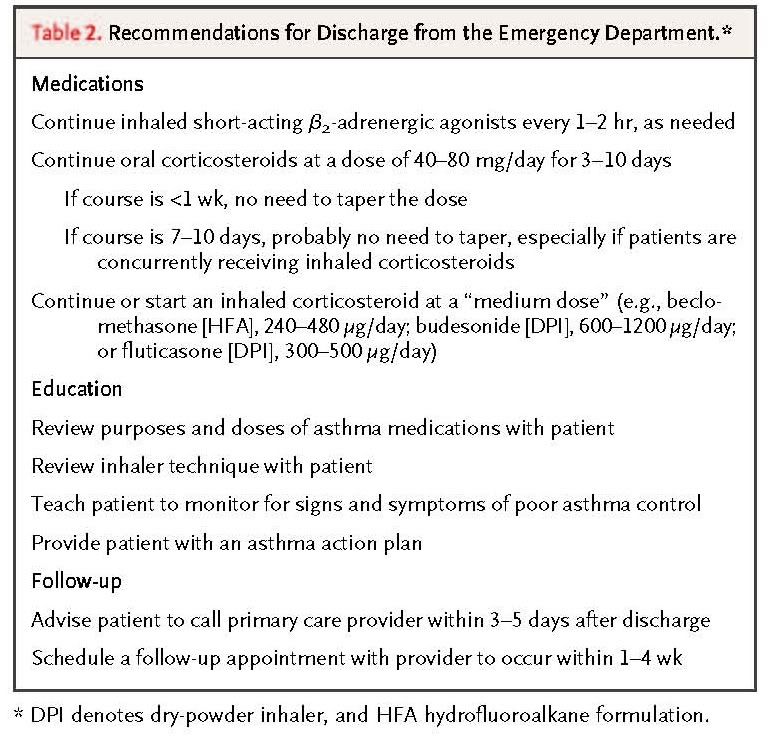

Patients may be discharged if the FEV1 or PEF after treatment is 70% or more of the personal best or predicted value and if the improvements in lung function and symptoms are sustained for at least 60 minutes. 3 After discharge, patients should continue to use inhaled short-acting β2-adrenergic agonists as needed and should be given oral corticosteroids for 3 to 10 days3 (Table 2 Recommendations for Discharge from the Emergency Department.). Inhaled corticosteroids can be started at any time during treatment of the exacerbation, but initiation at the time of discharge, if not before, is prudent to reduce the risk of relapse.27,42,43

Education of Patients

The need for treatment in the emergency department often reflects inadequate maintenance therapy and insufficient knowledge of how to deal with a worsening of asthma control. Presentation to the emergency department provides a unique opportunity to educate patients about medications, inhaler technique, and steps that can reduce exposure to household triggers of allergic reaction and to ensure that discharged patients have an asthma action plan and instructions for monitoring their symptoms and implementing their plan. A follow-up appointment should be scheduled with the patient's primary care provider or with an asthma specialist to occur 1 to 4 weeks after discharge. Guidelines also recommend that patients be encouraged to contact their asthma care provider within 3 to 5 days after discharge, when the risk of relapse is greatest,3 although data are lacking to show that this action improves outcomes.

Areas of Uncertainty

In patients with severe asthma that is refractory to standard treatment, intravenous magnesium sulfate is widely used,44 but there is controversy regarding its efficacy. A meta-analysis of 1669 patients in 24 studies who received either intravenous magnesium sulfate (used in 15 studies) or nebulized magnesium sulfate (used in 9 studies) showed that intravenous treatment was weakly associated with improved lung function in adults but had no significant effect on hospital admissions; in children, the use of intravenous magnesium sulfate significantly improved lung function and reduced rates of hospital admission. The effect of nebulized magnesium sulfate is less substantiated.45 Expert opinion46 and guidelines3 suggest that clinicians consider the use of intravenous magnesium sulfate in patients who have severe exacerbations and whose FEV1 or PEF remains less than 40% of the personal best or predicted value after initial treatments. The results of a large multicenter trial in the United Kingdom47 (Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN04417063) comparing treatment with intravenous or nebulized magnesium sulfate and standard treatment in patients with severe asthma are expected in 2011.

Heliox is a mixture of helium and oxygen, usually 79% and 21%, respectively, with a density about one third that of air, that reduces airflow resistance within regions of the bronchial tree where turbulent flow predominates. It is thought to reduce the work of breathing and to improve delivery of aerosolized medications. However, its role in the management of acute severe asthma is unclear. A Cochrane analysis of 544 patients in 10 trials led to the conclusion that heliox might be beneficial in patients with severe airflow obstruction who have not had a response to initial treatment,48 and current guidelines reflect this conclusion.3

Since the administration of oral leukotriene inhibitors results in increases in the FEV1 within 1 to 2 hours,49,50 there has been interest in using these agents in the emergency department, but their usefulness in that setting is unclear. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous montelukast in 583 adults whose FEV1 remained at 50% or less of the predicted value after 60 minutes of standard care, the use of montelukast significantly improved the FEV1 at 60 minutes but did not reduce the rate of hospitalization.51

Guidelines

The NAEPP and the Global Initiative for Asthma have developed and updated evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma.3,52 The recommendations in this article are consistent with these guidelines.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The patient described in the vignette has chronic uncontrolled asthma necessitating daily rescue use of albuterol, but she has not been receiving daily controller therapy. Her history of ICU admissions and excessive albuterol use indicate that she is at increased risk for death related to asthma.

Treatment with oxygen, aerosolized albuterol and ipratropium, and systemic corticosteroids should be initiated. The patient should be monitored closely and her signs and symptoms reassessed frequently, and a decision to admit or discharge her should be made within 4 hours after presentation. If she is discharged from the emergency department, she should be educated about medications, inhaler technique, and steps for monitoring symptoms and for managing exacerbations. Emergency department staff should provide her with a discharge plan, schedule a follow-up appointment, and ensure that she has adequate medications or prescriptions to last until that appointment. Because of her previous admissions to the ICU and her history of consistently poor asthma control, referral to an asthma specialist would be prudent.

References

- 1

Rowe BH,

Voaklander DC, Wang D, et al. Asthma presentations by adults to emergency

departments in Alberta, Canada: a large population-based study. Chest 2009;135:57-65

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

- 2

Moorman JE, Rudd

RA, Johnson CA, et al. National surveillance for asthma -- United States,

1980-2004. MMWR Surveill Summ 2007;56:1-54

Medline

- 3

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma: full report 2007. (Accessed July 23, 2010, at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf.)

- 4

Cates CJ, Crilly

JA, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist

treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2006;2:CD000052-CD000052

Medline

- 5

Dhuper S, Chandra A, Ahmed A, et al. Efficacy and cost comparisons of bronchodilatator administration between metered dose inhalers with disposable spacers and nebulizers for acute asthma in an inner-city adult population. J Emerg Med 2008 December 10 (Epub ahead of print).

- 6

Rodrigo GJ,

Rodrigo C. Continuous vs intermittent beta-agonists in the treatment of acute

adult asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Chest

2002;122:160-165

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

- 7

Camargo CA,

Spooner CH, Rowe BH. Continuous versus intermittent beta-agonists in the

treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2003;4:CD001115-CD001115

Medline

- 8

Carl JC, Myers TR,

Kirchner HL, Kercsmar CM. Comparison of racemic albuterol and levalbuterol for

treatment of acute asthma. J Pediatr

2003;143:731-736

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

- 9

Qureshi F,

Zaritsky A, Welch C, Meadows T, Burke BL. Clinical efficacy of racemic

albuterol versus levalbuterol for the treatment of acute pediatric asthma. Ann Emerg Med 2005;46:29-36

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

10. 10

Rodrigo GJ,

Rodrigo C. First-line therapy for adult patients with acute asthma receiving a

multiple-dose protocol of ipratropium bromide plus albuterol in the emergency

department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2000;161:1862-1868

Web

of Science | Medline

11. 11

Gelb AF, Karpel J,

Wise RA, Cassino C, Johnson P, Conoscenti CS. Bronchodilator efficacy of the

fixed combination of ipratropium and albuterol compared to albuterol alone in

moderate-to-severe persistent asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther

2008;21:630-636

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

12. 12

Plotnick LH, Ducharme

FM. Combined inhaled anticholinergics and beta2-agonists for initial treatment

of acute asthma in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2000;4:CD000060-CD000060

Medline

13. 13

Rodrigo GJ,

Castro-Rodriguez JA. Anticholinergics in the treatment of children and adults

with acute asthma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Thorax 2005;60:740-746[Erratum, Thorax 2008;63:1029,

2006;61:274, 458.]

Web

of Science | Medline

14. 14

Fanta CH, Rossing

TH, McFadden ER. Glucocorticoids in acute asthma: a critical controlled trial. Am J Med 1983;74:845-851

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

15. 15

Littenberg B,

Gluck EH. A controlled trial of methylprednisolone in the emergency treatment

of acute asthma. N Engl J Med 1986;314:150-152

Free

Full Text | Web

of Science | Medline

16. 16

Rodrigo G, Rodrigo

C. Corticosteroids in the emergency department therapy of acute adult asthma:

an evidence-based evaluation. Chest

1999;116:285-295

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

17. 17

Rowe BH, Edmonds

ML, Spooner CH, Diner B, Camargo CA. Corticosteroid therapy for acute asthma. Respir Med 2004;98:275-284

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

18. 18

Krishnan JA, Davis

SQ, Naureckas ET, Gibson P, Rowe BH. An umbrella review: corticosteroid therapy

for adults with acute asthma. Am J Med

2009;122:977-991

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

19. 19

Harrison BD,

Stokes TC, Hart GJ, Vaughan DA, Ali NJ, Robinson AA. Need for intravenous

hydrocortisone in addition to oral prednisolone in patients admitted to

hospital with severe asthma without ventilatory failure. Lancet

1986;1:181-184

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

20. 20

Ratto D, Alfaro C,

Sipsey J, Glovsky MM, Sharma OP. Are intravenous corticosteroids required in

status asthmaticus? JAMA 1988;260:527-529

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

21. 21

Jonsson S,

Kjartansson G, Gislason D, Helgason H. Comparison of the oral and intravenous

routes for treating asthma with methylprednisolone and theophylline. Chest 1988;94:723-726

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

22. 22

Engel T, Dirksen

A, Frolund L, et al. Methylprednisolone pulse therapy in acute severe asthma: a

randomized, double-blind study. Allergy

1990;45:224-230

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

23. 23

Bowler SD,

Mitchell CA, Armstrong JG. Corticosteroids in acute severe asthma:

effectiveness of low doses. Thorax 1992;47:584-587

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

24. 24

Emerman CL,

Cydulka RK. A randomized comparison of 100-mg vs 500-mg dose of

methylprednisolone in the treatment of acute asthma. Chest

1995;107:1559-1563

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

25. 25

Marquette CH,

Stach B, Cardot E, et al. High-dose and low-dose systemic corticosteroids are

equally efficient in acute severe asthma. Eur Respir J

1995;8:22-27[Erratum, Eur Respir J 1995;8:1435.]

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

26. 26

Edmonds ML,

Camargo CA, Pollack CV, Rowe BH. Early use of inhaled corticosteroids in the

emergency department treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2003;3:CD002308-CD002308

Medline

27. 27

Rowe BH, Bota GW,

Fabris L, Therrien SA, Milner RA, Jacono J. Inhaled budesonide in addition to

oral corticosteroids to prevent asthma relapse following discharge from the

emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA

1999;281:2119-2126

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

28. 28

Parameswaran K,

Belda J, Rowe BH. Addition of intravenous aminophylline to beta2-agonists in

adults with acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2000;4:CD002742-CD002742

Medline

29. 29

Karpel JP, Aldrich

TK, Prezant DJ, Guguchev K, Gaitan-Salas A, Pathiparti R. Emergency treatment

of acute asthma with albuterol metered-dose inhaler plus holding chamber: how

often should treatments be administered? Chest

1997;112:348-356

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

30. 30

Strauss L, Hejal

R, Galan G, Dixon L, McFadden ER. Observations on the effects of aerosolized

albuterol in acute asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1997;155:454-458

Web

of Science | Medline

31. 31

Rodrigo C, Rodrigo

G. Therapeutic response patterns to high and cumulative doses of salbutamol in

acute severe asthma. Chest 1998;113:593-598

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

32. 32

Rodrigo G, Rodrigo

C. Early prediction of poor response in acute asthma patients in the emergency

department. Chest 1998;114:1016-1021

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

33. 33

Chey T, Jalaludin

B, Hanson R, Leeder S. Validation of a predictive model for asthma admission in

children: how accurate is it for predicting admissions? J

Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:1157-1163

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

34. 34

McCarren M,

Zalenski RJ, McDermott M, Kaur K. Predicting recovery from acute asthma in an

emergency diagnostic and treatment unit. Acad Emerg Med

2000;7:28-35

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

35. 35

Karras DJ, Sammon

ME, Terregino CA, Lopez BL, Griswold SK, Arnold GK. Clinically meaningful

changes in quantitative measures of asthma severity. Acad

Emerg Med 2000;7:327-334

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

36. 36

Smith SR, Baty JD,

Hodge D. Validation of the pulmonary score: an asthma severity score for

children. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:99-104

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

37. 37

Gorelick MH,

Stevens MW, Schultz TR, Scribano PV. Performance of a novel clinical score, the

Pediatric Asthma Severity Score (PASS), in the evaluation of acute asthma. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:10-18

Web

of Science | Medline

38. 38

Kelly AM, Kerr D,

Powell C. Is severity assessment after one hour of treatment better for

predicting the need for admission in acute asthma? Respir

Med 2004;98:777-781

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

39. 39

Darioli R, Perret

C. Mechanical controlled hypoventilation in status asthmaticus. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;129:385-387

Medline

40. 40

Thill PJ, McGuire

JK, Baden HP, Green TP, Checchia PA. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation

in children with lower airway obstruction. Pediatr Crit

Care Med 2004;5:337-342[Erratum, Pediatr Crit Care Med 2004;5:590.]

CrossRef

| Medline

41. 41

Soroksky A, Stav

D, Shpirer I. A pilot prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of

bilevel positive airway pressure in acute asthmatic attack. Chest 2003;123:1018-1025

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

42. 42

Blais L, Ernst P,

Boivin JF, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of readmission

to hospital for asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1998;158:126-132

Web

of Science | Medline

43. 43

Sin DD, Man SF.

Low-dose inhaled corticosteroid therapy and risk of emergency department visits

for asthma. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1591-1595

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

44. 44

Jones LA, Goodacre

S. Magnesium sulphate in the treatment of acute asthma: evaluation of current

practice in adult emergency departments. Emerg Med J

2009;26:783-785

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

45. 45

Mohammed S,

Goodacre S. Intravenous and nebulised magnesium sulphate for acute asthma:

systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J

2007;24:823-830

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

46. 46

Rowe BH, Camargo

CA. The role of magnesium sulfate in the acute and chronic management of

asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2008;14:70-76

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

47. 47

NIHR Health Technology Assessment Program. The 3Mg Trial: randomised controlled trial of intravenous or nebulised magnesium sulphate or standard therapy for acute severe asthma. 2010. (Accessed July 23, 2010, at http://www.hta.ac.uk/project/1619.asp.)

48. 48

Rodrigo G, Pollack

C, Rodrigo C, Rowe BH. Heliox for nonintubated acute asthma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;4:CD002884-CD002884

Medline

49. 49

Liu MC, Dube LM,

Lancaster J. Acute and chronic effects of a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor in asthma:

a 6-month randomized multicenter trial. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 1996;98:859-871

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

50. 50

Dockhorn RJ,

Baumgartner RA, Leff JA, et al. Comparison of the effects of intravenous and

oral montelukast on airway function: a double blind, placebo controlled, three

period, crossover study in asthmatic patients. Thorax

2000;55:260-265

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

51. 51

Camargo CA, Gurner

DM, Smithline HA, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled study of intravenous

montelukast for the treatment of acute asthma. J Allergy

Clin Immunol 2010;125:374-380

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

52. 52

Bateman ED, Hurd

SS, Barnes PJ, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention:

GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J

2008;31:143-178

CrossRef

| Web

of Science | Medline

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢