Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic tumors in the Western world.1Approximately 80% of patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer have a response to platinum-based chemotherapy. However, most patients have relapses, and responses to subsequent therapies are generally short-lived.2-6 Maintenance chemotherapy as part of first-line treatment has been shown to prolong control of ovarian cancer,7 and disease control has also been prolonged with the combination of bevacizumab and chemotherapy in patients receiving first-line treatment8,9 and in those with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer.10 However, new treatments are needed because most patients eventually have a relapse.

Women with germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, or both (BRCA1/2) have an increased risk of ovarian cancer, particularly the most common type, invasive high-grade serous carcinoma.11 About 15% of epithelial ovarian cancers are deficient in homologous recombination repair, owing to mutations in BRCA1/2.12,13 In up to 50% of patients with high-grade serous tumors, the tumor cells may be deficient in homologous recombination as a result of germline or somatically acquiredBRCA1/2 mutations, epigenetic inactivation of BRCA1, or defects in the homologous recombination pathway that are independent of BRCA1/2.14 The silencing or dysfunction of genes in BRCA1/2-related pathways gives rise to a “BRCAness” phenotype similar to that resulting from inherent mutations in BRCA1/2. Microarray studies in serous epithelial ovarian cancer have identified a BRCAness gene-expression profile that appears to correlate with responsiveness to both platinum-based chemotherapy and poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.15,16

PARP plays an essential part in the repair of single-stranded DNA breaks, through the base-excision-repair pathway, and it has been proposed that PARP keeps low-fidelity nonhomologous-end-joining DNA repair machinery in check.17 Thus, PARP inhibition leads to the formation of double-stranded DNA breaks that cannot be accurately repaired in tumors with homologous recombination deficiency,18,19 owing to aberrant activation of low-fidelity repair mediated by nonhomologous end joining,17 a concept known as synthetic lethality.20 Olaparib (AZD2281) is a potent oral PARP inhibitor that induces synthetic lethality in BRCA1/2-deficient tumor cells.21,22Antitumor activity at doses that were not unacceptably toxic was observed in phase 1 and phase 2 monotherapy studies involving patients with ovarian cancer who had BRCA1/2 germline mutations.23-25 In addition, a phase 2 study of olaparib monotherapy in patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer with or without BRCA1/2 mutations showed objective response rates of 41% for patients with BRCA1/2 mutations and 24% for those without such mutations.26

We evaluated the efficacy of olaparib monotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, high-grade serous ovarian cancer who had had a response to their most recent platinum-based chemotherapy.

RESULTS

Patients

Between August 28, 2008, and February 9, 2010, we screened 326 patients at 82 investigational sites in 16 countries. Of the 265 patients who met the eligibility criteria, 136 were randomly assigned to receive olaparib, at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, and 129 to receive placebo (Figure 1). At the data-cutoff point (June 30, 2010), 68 patients (50%) in the olaparib group and 21 (16%) in the placebo group were still receiving the study treatment. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients (Table 1

TABLE 1Demographic and Baseline Characteristics of the Patients.) and any protocol deviations with the potential to affect the primary analysis (Table 1 in the Supplementary Appendix) were well balanced between the two study groups.

Efficacy

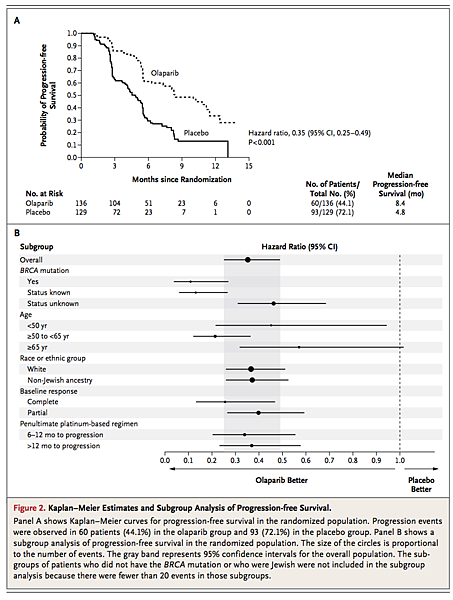

An analysis performed after 153 progression events had occurred (in 57.7% of patients) showed that progression-free survival was significantly longer in the olaparib group than in the placebo group. Median progression-free survival was 8.4 months in the olaparib group versus 4.8 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio for progression or death, 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25 to 0.49; P<0.001) (Figure 2A

FIGURE 2Kaplan–Meier Estimates and Subgroup Analysis of Progression-free Survival.). A stratified log-rank test of progression-free survival supported the primary analysis (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.51; P<0.001). A blinded, independent, central review of the data also showed consistent results (hazard ratio, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.27 to 0.55; P<0.001). Subgroup analyses of progression-free survival showed that, regardless of subgroup, patients in the olaparib group had a lower risk of progression than those in the placebo group (Figure 2B). No predictive factors were identified (global treatment-by-subgroup interaction test, P=0.15). A complete response (vs. partial response) to the final platinum-based therapy before study entry was a significant prognostic factor for longer progression-free survival, regardless of study group (hazard ratio, 0.46; P<0.001).

The secondary end point of time to progression according to the RECIST guidelines or CA-125 level, whichever showed earlier progression, was also significantly longer in the olaparib group than in the placebo group (median, 8.3 months vs. 3.7 months; hazard ratio for progression, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.47; P<0.001). At study entry, 40% of the overall study population had measurable disease and could be assessed for an objective response according to RECIST guidelines; the response rate was 12% (7 of 57 patients with measurable disease at study entry) in the olaparib group, as compared with 4% (2 of 48) in the placebo group (odds ratio, 3.36; 95% CI, 0.75 to 23.72; P=0.12). At the time of the data-cutoff point for progression-free survival, too few deaths had occurred for a survival analysis to be performed. However, at the interim analysis of overall survival (data-cutoff point, October 31, 2011), 101 patients (38%) had died: 52 in the olaparib group and 49 in the placebo group. No significant difference in overall survival was observed (hazard ratio for death in the olaparib group, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.39; P=0.75). The median overall survival was similar in the two study groups (29.7 months in the olaparib group and 29.9 months in the placebo group). At the time of the interim analysis of overall survival, 29 patients were still receiving olaparib after a period of at least 21 months, and 4 patients were still receiving placebo. The secondary end points of change in tumor size, combined response rate according to RECIST guidelines and CA-125 measurement (Table 2 in the Supplementary Appendix), and disease-control rate are reported in the Supplementary Appendix.

Safety

The majority of patients (246 of 264) had one or more adverse events, most of which were grade 1 or 2 (Table 2

TABLE 2Adverse Events.). Adverse events with an incidence that was at least 10% higher in the olaparib group than in the placebo group, were nausea, fatigue, vomiting, and anemia. In both groups, nausea, fatigue, and vomiting were intermittent and did not require discontinuation of the study treatment. The incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was 35.3% in the olaparib group and 20.3% in the placebo group (Table 2). A total of seven grade 4 events were reported in the olaparib group (in 5.1% of patients), and two were reported in the placebo group (in 1.6% of patients) (Table 3

TABLE 3 Grade 4 Adverse Events.). There were no unexpected changes in biochemical laboratory measurements, vital signs, or findings on physical examination in either group.

At the time of the data-cutoff point, the median duration of exposure to the treatment was 206.5 days (range, 3 to 469) for olaparib and 141 days (range, 34 to 413) for placebo, and the mean rate of adherence to the assigned study treatment was 85% and 96%, respectively. More patients in the olaparib group had dose interruptions or reductions (27.9% and 22.8%, respectively) as a result of adverse events, as compared with the placebo group (8.6% and 4.7%). The most common adverse events that resulted in interruptions or reductions in the dose of olaparib were vomiting, nausea, and fatigue. Adverse events that led to the permanent discontinuation of treatment occurred in three patients receiving olaparib (one each with palpitations and myalgia, erythematous rash, and nausea and obstruction in the small intestine) and in one patient receiving placebo (nausea); all these adverse events were grade 2 and were considered by the investigator to be related to treatment, except for the grade 4 obstruction in the small intestine.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

There were no significant between-group differences in disease-related symptoms or rates of improvement in health-related quality of life, as measured by scores on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)–Ovarian questionnaire, the FACT–National Comprehensive Cancer Network Ovarian Symptom Index, and the Trial Outcome Index (Table 3 in the Supplementary Appendix).29 The time to worsening of each of these end points was shorter with olaparib than with placebo; however, the difference was not significant (Table 4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This randomized, phase 2 clinical trial involving patients with recurrent platinum-sensitive, high-grade serous ovarian cancer targeted a histologically and phenotypically defined subgroup of patients who have tumor cells that are highly enriched for homologous-recombination deficiency. In this population, maintenance therapy with olaparib, at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, significantly improved the duration of progression-free survival, as compared with placebo. Furthermore, the lower risk of disease progression associated with olaparib treatment was consistent across all the subgroups analyzed (Figure 2B). A significant benefit in the secondary end points of time to progression, as assessed by means of RECIST guidelines or CA-125 level, whichever showed earlier progression, and change in tumor size at 24 weeks was also observed in patients receiving olaparib. The identical hazard ratios for the primary end point of progression-free survival, according to RECIST guidelines, and for the secondary progression end point that also incorporated objective CA-125 measurements further support the validity of the significant improvement in progression-free survival. However, the observed benefit with respect to progression-free survival did not translate into an overall survival benefit at the time of the interim analysis of overall survival. Our data cannot address differences that might exist between patients with BRCA germline mutations and those with a BRCAness phenotype; it will be important to address these questions at the final analysis of overall survival.

There is a need to identify biomarkers to select patients for this therapy. The identification of biomarkers for homologous-recombination deficiency may provide an opportunity to target PARP inhibitors to the appropriate population. A recent study showed that the formation of Rad51 foci correlated with an in vitro response to PARP inhibition in primary epithelial ovarian-cancer cells.30Rad51 is involved in homologous recombination repair; it is relocalized to the nucleus in response to DNA damage to form distinct foci that are thought to be assemblages of proteins required for homologous recombination repair.

The toxicity profile of olaparib in this patient population was consistent with that reported in previous clinical studies.24,25,31 The majority of adverse events were grade 1 or 2 and did not require interruptions of the treatment. Dose modifications were more common in the olaparib group; however, discontinuations due to adverse events were infrequent, and adherence to therapy was high. There were no significant differences between the study groups in the end points for symptoms or health-related quality of life.

The median progression-free survival of 4.8 months from randomization in the placebo group was shorter than the expected progression-free survival specified in the protocol (9 months). At the time that the study was designed, there were no reported data from trials of maintenance treatment in patients with a relapse of platinum-responsive ovarian cancer, which would have provided a basis for estimating progression-free survival in the placebo group. However, the observed value of 4.8 months is consistent with recently published data from studies of maintenance treatment in similar patient populations (5.8 months and 2.8 months),32,33 suggesting that progression-free survival in the placebo group in our study was in line with that expected.

Because only patients with a response to chemotherapy were enrolled in the study, just 40% had measurable disease at entry. Objective response was not an informative end point because there were limited opportunities for further responses. Response rates were low in both study groups, and some patients in the placebo group had a reduction in tumor size.

In conclusion, the results from this randomized, phase 2 study show that maintenance treatment with olaparib was associated with a significant improvement in progression-free survival among patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, high-grade serous ovarian cancer. However, at the interim analysis, this did not translate into an overall survival benefit. As of this writing, 21% of the patients were still receiving olaparib (and 3% were still receiving placebo), which indicates that the disease is controlled for a prolonged period in some patients.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢