Roger Kurlan, M.D.

N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2332-2338

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the author's clinical recommendations.

A 9-year-old boy has a 3-year history of hyperactive behavior, distractibility, and inattention. He is starting to fall behind in school. During the past year, he has had frequent eye blinking and throat clearing. How should he be evaluated and treated?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Tourette's syndrome (sometimes called Tourette's disorder) is a childhood-onset condition characterized by motor and vocal tics that are chronic (duration of >1 year). The standard diagnostic criteria for Tourette's syndrome are listed in Table1

Motor tics include simple tics such as twitching, eye blinking, facial grimacing, or head jerking; slow twisting movements (dystonic tics); isometric contractions (tonic tics) such as tensing of the abdominal muscles; and more complicated, purposeful-looking movements (complex motor tics) such as touching or tapping. Vocal tics (also called phonic tics) include inarticulate noises such as throat clearing, sniffing, or coughing (simple vocal tics) and words or partial words (complex vocal tics). Because of the nature of tics, children are often referred to ophthalmologists or allergists before they receive the proper diagnosis of tics. Virtually any movement or sound that the human body is capable of making can be a manifestation of a tic. The most notorious tic of Tourette's syndrome, obscene or insulting utterances (coprolalia), occurs in less than 50% of cases in reported series.

Tics are often preceded by premonitory urges or uncomfortable sensations that are usually localized at the site of the tic; patients frequently report that their tics relieve the sensations.3 Tics have been described as “unvoluntary,” meaning there is some ability initially to voluntarily suppress their expression, but the urges and sensations build until there is an irresistible impulse to release the tics. Children tend to suppress tics (sometimes subconsciously) in socially sensitive places such as school or church; this suppression often leads to a sense of mental fatigue. Most patients with Tourette's syndrome have multiple types of tics that vary in type over time; these tics occur in waves and vary in frequency and intensity from week to week or month to month. Although tics tend to worsen during times of stress, the waxing and waning of tics is a characteristic of the natural history of Tourette's syndrome, and exacerbations are not necessarily linked to any type of emotional problem.

Tourette's syndrome is now viewed as a neuropsychiatric spectrum disorder in which tics are commonly associated with obsessive−compulsive symptoms that do not always meet the full diagnostic criteria for obsessive−compulsive disorder (OCD) and with disturbances of attention that do not always meet the full criteria for attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).4 The combination of tics, OCD, and ADHD is often called “the Tourette's syndrome triad.” Studies have suggested a familial aggregation and hereditary relationship among these three conditions. 5,6Evidence suggests that boys are more likely to have tics and ADHD, whereas girls are more likely to have OCD.7 Other psychiatric problems that are reported to occur more frequently in children with Tourette's syndrome than in children without Tourette's syndrome include rage attacks, depression, bipolar disorder, impulse-control problems, and anxiety, although their prevalence and the exact nature of their relationship to Tourette's syndrome remain unclear. For example, some behavioral problems may arise from difficulties in living with Tourette's syndrome.

The prevalence of Tourette's syndrome among children is estimated to be approximately 1%.8 Risk factors for this condition include male sex and a family history of tics, OCD, and possibly ADHD.

Most longitudinal and retrospective studies suggest that as children grow into adolescence and adulthood, tics resolve in about one third of cases and become substantially less severe in another third.9,10, In the remainder of cases, Tourette's syndrome is lifelong, with no substantial reduction of symptoms. There are no known reliable predictors of the ultimate outcome. For patients who do have improvement in symptoms, tics typically begin to lessen in severity at approximately 13 years of age, but they may not resolve until 30 years of age. Data from well-designed longitudinal studies of Tourette's syndrome are lacking, and information on the natural course of the condition is thus limited.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of Tourette's syndrome is made when motor and vocal tics have been present for at least 1 year.1 The temporal criterion is used to distinguish the tics of Tourette's syndrome from identical-appearing tics that can occur transiently during normal development.11 Traditional diagnostic distinctions between Tourette's syndrome and conditions such as chronic motor tic disorder and chronic vocal tic disorder in which there are motor or vocal tics, but not both, are probably invalid from a neurobiologic perspective, since chronic motor or vocal tic disorder and Tourette's syndrome are believed to result from similar mechanisms. Thus, most clinicians now consider patients who have chronic motor or vocal tics or both types of tics to have Tourette's syndrome.

Tics should be distinguished from compulsions. Unlike tics, compulsions occur in response to an obsession (e.g., hand washing due to fear of contamination), according to rules (e.g., a certain number of times or in a certain order), or to ward off harm to self or others. However, tics and compulsions commonly coexist and have phenomenologies that are so similar that sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between them.12

Tics commonly accompany developmental disorders such as mental retardation, autism, and Asperger's syndrome,13 and many experts do not diagnose Tourette's syndrome when these other disorders are present. In these cases, the tics are considered to be secondary to the developmental disorder. Other neurologic disorders can also cause tics, but these disorders are rare.

In most children, the diagnosis of Tourette's syndrome is made clinically; neuroimaging or other laboratory testing is not necessary to establish the diagnosis.14 Tic suppression is common in physicians' offices, and the best time to look for tics is when the patient is walking into or out of the examination room. Clinical rating scales that can be used to assess the child for coexisting psychiatric conditions include the Yale−Brown Obsessive−Compulsive Scale,15 the Conners Parent or Teacher ADHD Rating Scales,16 and the Child Depression Inventory.17

Management

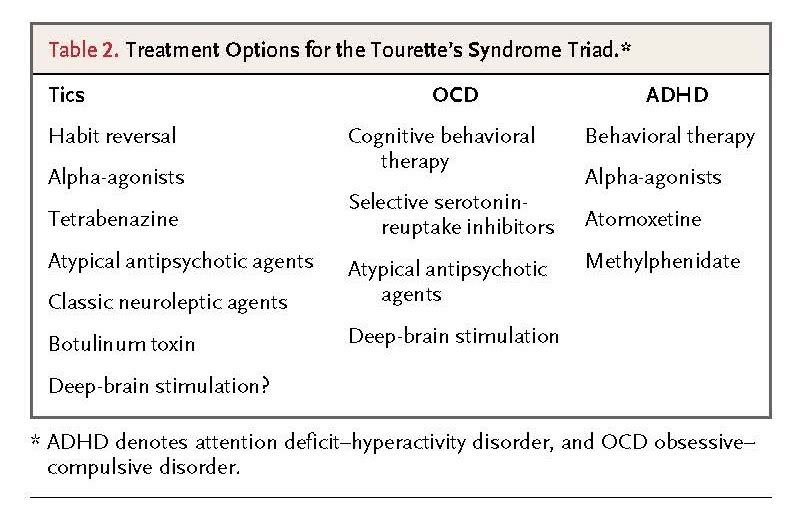

In many children with Tourette's syndrome, tics are mild and not disabling, and education about the condition with some supportive counseling is sufficient. A key focus is on maintaining and strengthening the child's self-confidence and self-esteem. Supportive counseling may be helpful for these purposes, although it has not been rigorously studied. Tics can be disabling by causing social embarrassment, isolation, and sometimes conflict (e.g., because of vocal insults). Some tics (e.g., neck jerking) are painful, and some (e.g., scratching and poking) can be self-injurious. When tics are disabling, tic-suppressing therapy is indicated. General approaches to treating Tourette's syndrome and its common coexisting conditions are summarized in Table 2

Behavioral Therapy

Clinical trials have shown that a form of cognitive behavioral therapy termed habit-reversal treatment is efficacious in suppressing tics. This form of therapy involves training patients to monitor their tics and premonitory sensations and to respond to them with a voluntary behavior that is physically incompatible with the tics.18 In a clinical trial that compared habit-reversal treatment with supportive therapy and education, habit reversal (carried out in eight weekly sessions) resulted in modestly greater improvement as measured by the score on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale at 10 weeks (mean score reduction, 7.6 vs. 3.5 points). This two-part scale measures the severity of tics and overall impairment; scores for each part range from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater disability, and a change in the total score of 2.5 to 5.0 points is considered a minimal clinically significant difference. Potential shortcomings of habit-reversal therapy are that it is not widely available, it is time-consuming, and its long-term benefits have not been examined. Its clinical value remains controversial, but some experts advocate trying this therapy before initiating medication in cases that are not severe.

Pharmacotherapy

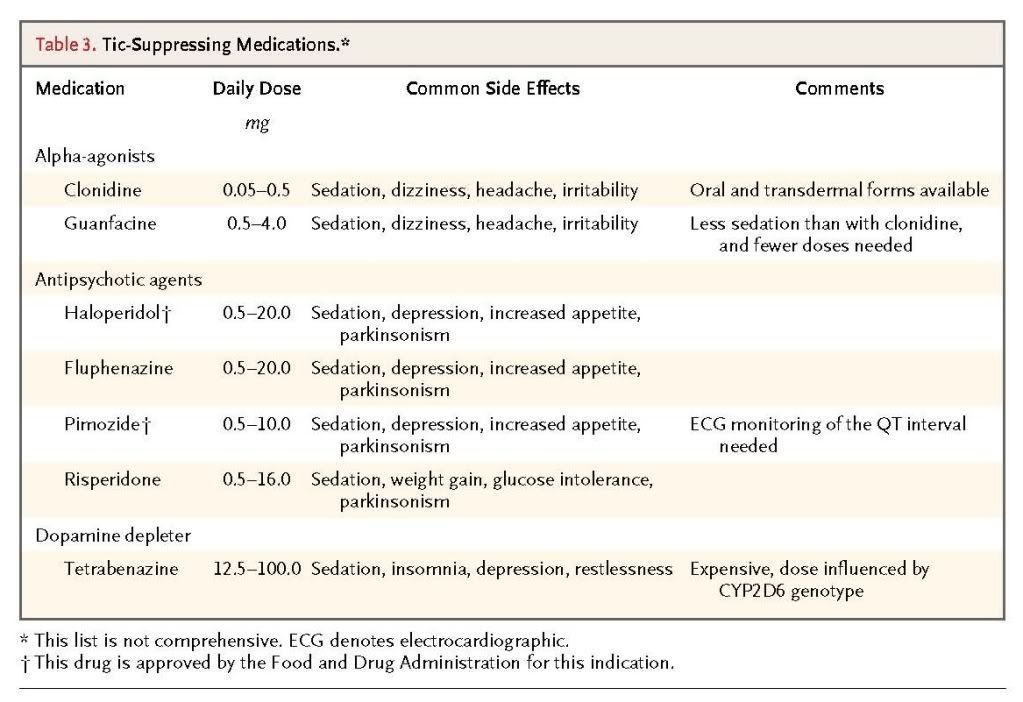

The only medications for Tourette's syndrome that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are the classic neuroleptic antipsychotic agents haloperidol and pimozide, which block D2 dopamine receptors (Table 3)

Data from controlled clinical trials provide support for their efficacy,19,20 although many of these early trials used outcome measures that were not standardized. Long-term tic control often requires long-term therapy. In a controlled trial involving patients whose tics were controlled after 1 to 3 months of pimozide therapy, the mean time to relapse (as defined by the need for an increase in drug dosage) was significantly shorter for patients in whom therapy was withdrawn (the placebo group) than for those who continued to receive medication (37 vs. 231 days).21

Randomized, controlled trials have also provided support for the efficacy of a newer atypical antipsychotic agent, risperidone, in suppressing tics, with a magnitude of benefit that is similar to that of the classic neuroleptics.22,23, One study, for example, showed a mean reduction of 32% in the score for the tic portion of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale after 8 weeks of treatment, as compared with a 7% reduction among patients who received placebo. 23 Observational data suggest that some of the other members of this drug class may likewise lessen the severity of tics. The most frequent side effects of all antipsychotic agents are sedation, depression, increased appetite, and parkinsonism. Although the atypical antipsychotics have fewer motor complications, such as parkinsonism, they commonly induce weight gain (which is often pronounced),24 and glucose intolerance (the metabolic syndrome), and these risks must be taken into account in selecting therapy for children with Tourette's syndrome.

Although studies have shown that antipsychotics are efficacious in suppressing tics, because of their frequent side effects, other medications are often used first. Several trials have provided support for the efficacy of the α2-adrenergic drugs clonidine and guanfacine.25-27 The magnitudes of benefit reported are generally lower than those associated with the antipsychotics, although no head-to-head comparisons have been published. Since they also have efficacy for ADHD, the alpha-agonists may be a good choice in patients with both tics and ADHD.27,28 Common side effects of the alpha-agonists are sedation, dizziness, headache, and irritability. Hypotension is generally not a problem, although syncope is a rare side effect. Guanfacine is usually preferred because it tends to cause less sedation and can be given once (at bedtime) or twice daily as compared with three or four daily doses of clonidine. A transdermal form of clonidine is available and useful in children who cannot swallow pills.29

Tetrabenazine is a drug that depletes presynaptic dopamine and, in case series, has been reported to reduce tics.30,31 Some clinicians recommend tetrabenazine as a first-line treatment for tics, since tardive dyskinesia has not been reported with its use. No comparison trials have been performed to determine the best initial medication. The most common side effects of tetrabenazine are sedation, insomnia, restlessness, and depression.

A recent small clinical trial showed that topiramate is effective for tics.32 There is inadequate evidence to recommend other medications suggested to lessen tics, including clonazepam, levetiracetam, and baclofen.

It is common practice to combine drug classes, such as an antipsychotic and an alpha-agonist. However, in the treatment of tics, this approach has not been studied systematically.

Botulinum Toxin

Local intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin is a therapeutic option for some types of particularly bothersome tics, although data from controlled trials are lacking. Case series indicate that this treatment can reduce tics as well as associated premonitory sensations and pain.33,34 Botulinum toxin is used most frequently for eye blinking and neck and shoulder tics. The benefits are temporary, lasting 3 to 6 months.

Deep-Brain Stimulation

Surgical treatment with deep-brain stimulation has recently been used in patients with Tourette's syndrome who have disabling tics that are refractory to medication. The results of double-blind trials of thalamic stimulation with the use of a crossover design (comparing stimulation on with stimulation off) indicate that some patients have a substantial benefit.35,36 The largest published trial showed a mean reduction of 29% in the score on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale during stimulation. However, the criteria for identifying patients with Tourette's syndrome who will have the greatest benefit from deep-brain stimulation have not been established, and the optimal location for the electrodes in such patients is not clear; the globus pallidus, putamen, subthalamic nucleus, and other areas have been used. Deep-brain stimulation can be complicated by stroke, infection, and side effects during stimulation such as paresthesias, visual symptoms, and dysarthria.

Management of Coexisting Conditions

An important part of treating patients with Tourette's syndrome is the appropriate treatment of coexisting conditions. A detailed discussion of the management of ADHD, OCD, and other coexisting conditions is beyond the scope of this article.37,38 In brief, cognitive behavioral therapy, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, and atypical antipsychotics are established therapies for OCD; deep-brain stimulation has been shown to be effective in severe cases. There has been concern that the use of psychostimulant drugs for coexisting ADHD might exacerbate tics in patients with Tourette's syndrome because of the pharmacologic effects on catecholamine neurotransmission. However, a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving children with both Tourette's syndrome and ADHD showed that methylphenidate was effective for ADHD and did not exacerbate tics.28 Another multicenter, controlled trial showed that the selective norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine likewise was associated with improvement of ADHD symptoms without worsening of tics in children with both conditions.39 Other stimulants, such as dextroamphetamine sulfate and amphetamine salts, have not been studied in controlled trials involving patients with Tourette's syndrome.

Given the fact that many patients with Tourette's syndrome require treatment for both tics and coexisting conditions, combination therapy with tic-suppressing, anti-OCD, and anti-ADHD medications is commonly used. No formal assessments of such combination therapy have been reported.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Although there is evidence of a state of excessive central dopamine neurotransmission in Tourette's syndrome, the fundamental cause of the illness and its neurobiologic mechanisms remain poorly understood. Neuroimaging studies have shown volumetric changes in the basal ganglia and other brain regions, but the results have not been consistent.40 Neuroimaging has not identified increases in striatal presynaptic monoaminergic vesicles41 or striatal dopaminergic innervation42 in patients with Tourette's syndrome as compared with controls. Family studies suggest a complex inheritance pattern in Tourette's syndrome43 that often includes bilineal (maternal and paternal) transmission.44 Associations have been reported between Tourette's syndrome and some genetic loci,45,46 but they appear to account for only a small portion of cases. Tourette's syndrome has also been associated with recurrent exonic copy-number variants (DNA deletions and duplications),47 which appear to be involved in a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders.48

The observation that Tourette's syndrome resolves or becomes less severe in a substantial number of patients as they grow into adulthood suggests that the underlying mechanisms involve processes that may correct themselves as the brain matures. On the basis of clinical similarities between Sydenham's chorea and Tourette's syndrome with OCD, the PANDAS syndrome (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections) was hypothesized as an autoimmune response to streptococcal infection that might precipitate or exacerbate tics. A recent intensive, prospective, blinded, clinical and laboratory cohort study, however, did not identify any temporal link between streptococcal infection and clinical exacerbations in patients who met the criteria for PANDAS.49

GUIDELINES

The Practice Parameter Group of the Tourette Syndrome Association has published recommendations for the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of Tourette's syndrome and associated psychiatric conditions.14 The group emphasized the importance of accurate diagnosis, including identification of coexisting conditions. For the treatment of Tourette's syndrome, the recommendations are that guanfacine or clonidine be considered as a first-line medication for moderate or more severe tics, that botulinum toxin may be considered in patients with a single interfering tic, and that more potent medications such as risperidone, pimozide, or fluphenazine may be considered for tics with an inadequate response to the alpha-agonists. A report by the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, which focused on neurologic uses of botulinum toxin therapy, concluded that it is an appropriate treatment for tics in patients with Tourette's syndrome.34

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The boy described in the case vignette has had motor and vocal tics for more than 1 year, suggesting the diagnosis of Tourette's syndrome. His problems with performance in school may be explained in part by his tics (e.g., eye-blinking tics affect reading, arm tics affect writing, and the mental effort expended in suppressing tics affects attention and concentration). His history of inattention and hyperactivity suggests possible coexisting ADHD, but problems with attention and focusing can also be due to obsessive thinking, compulsions, anxiety, or low mood. The patient should be evaluated for these potential coexisting conditions. For combined Tourette's syndrome and ADHD, guanfacine would be a good first-choice medication, since it can improve both conditions, although this agent is not approved by the FDA for these conditions. If control of tics is inadequate, adding an antipsychotic drug would be reasonable. Inadequate control of ADHD would warrant the addition of a methylphenidate preparation.

REFERENCES

-

1

Diagnostic and statistical manual of psychiatry. 4th ed. rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

-

2

Freeman RD, Zinner SH, Muller-Vahl KR, et al. Coprophenomena in Tourette syndrome.Dev Med Child Neurol 2009;51:218-227

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

3

Leckman JF, Walker DE, Cohen DJ. Premonitory urges in Tourette's syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:98-102

Web of Science | Medline -

4

Jankovic J. Tourette's syndrome. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1184-1192

Full Text | Web of Science | Medline -

5

Pauls DL, Towbin KE, Leckman JF, Zahner GE, Cohen DJ. Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence supporting a genetic relationship.Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:1180-1182

Web of Science | Medline -

6

Comings DE, Comings BG. Tourette's syndrome and attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity: are they genetically related? J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1984;23:138-146

CrossRef | Medline -

7

Pauls DL, Leckman JF. The inheritance of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and associated behaviors: evidence for autosomal dominant transmission. N Engl J Med 1986;315:993-997

Full Text | Web of Science | Medline -

8

Robertson MM. The prevalence and epidemiology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. I. The epidemiological and prevalence studies. J Psychosom Res 2008;65:461-472

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

9

Singer HS, Walkup JT. Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991;70:15-32

Web of Science | Medline -

10

Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, et al. Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades. Pediatrics 1998;102:14-19

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

11

Kurlan R. Hypothesis II: Tourette's syndrome is part of a clinical spectrum that includes normal brain development. Arch Neurol 1994;51:1145-1150

Web of Science | Medline -

12

Palumbo D, Kurlan R. Complex obsessive compulsive and impulsive symptoms in Tourette's syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2007;3:687-693

Medline -

13

Ringman JM, Jankovic J. Occurrence of tics in Asperger's syndrome and autistic disorder.J Child Neurol 2000;15:394-400

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

14

Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM, et al. Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome. NeuroRx 2006;3:192-206

CrossRef | Medline -

15

Goodman WK, Price LM, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:1006-1011

Web of Science | Medline -

16

Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF. Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1978;6:221-236

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

17

Kovacs M. Child Depression Inventory — short version. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, 1999.

-

18

Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, et al. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1929-1937

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

19

Pringsheim T, Marras C. Pimozide for tics in Tourette's syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD006996-CD006996

Medline -

20

Sallee FR, Nesbitt L, Jackson C, Sine L, Sethuraman G. Relative efficacy of haloperidol and pimozide in children and adolescents with Tourette's disorder. Am J Psychiatry1997;154:1057-1062

Web of Science | Medline -

21

Tourette Syndrome Study Group. Short-term vs. longer term pimozide therapy in Tourette's syndrome: a preliminary study. Neurology 1999;52:874-877

Web of Science | Medline -

22

Dion Y, Annable L, Sandor P, Chouinard G. Risperidone in the treatment of Tourette syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;22:31-39

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

23

Scahill L, Leckman JF, Schultz RT, Katsovich L, Peterson BS. A placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in Tourette syndrome. Neurology 2003;60:1130-1135

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

24

Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1686-1689

Web of Science | Medline -

25

Goetz CG, Tanner CM, Wilson RS, Carroll VS, Como PG, Shannon KM. Clonidine and Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome: double-blind study using objective rating measures. Ann Neurol 1987;21:307-310

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

26

Leckman JF, Hardin MT, Riddle MA, Stevenson J, Orf SI, Cohen DJ. Clonidine treatment of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:324-328

Web of Science | Medline -

27

Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, et al. A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1067-1074

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

28

Tourette's Syndrome Study Group. Treatment of ADHD in children with tics: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2002;58:527-536

Web of Science | Medline -

29

Du YS, Li HF, Vance A, et al. Randomized double-blind multicentre placebo-controlled clinical trial of the clonidine adhesive patch for the treatment of tic disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008;42:807-813

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

30

Kenney CJ, Hunter CB, Mejia NI, Jankovic J. Tetrabenazine in the treatment of Tourette syndrome. J Pediatr Neurol 2007;5:9-13

-

31

Porta M, Sassi M, Cavallazzi M, et al. Tourette's syndrome and role of tetrabenazine: review and personal experience. Clin Drug Investig 2008;28:443-459

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

32

Jankovic J, Jimenez-Shahed J, Brown LW. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of topiramate in the treatment of Tourette syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2010;81:70-73

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

33

Kwak CH, Hanna PA, Jankovic J. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of tics. Arch Neurol2000;57:1190-1193

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

34

Simpson DM, Blitzer A, Brashear A, et al. Assessment: botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of movement disorders (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology.Neurology 2008;70:1699-1706

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

35

Maciunas RJ, Maddux BN, Riley DE, et al. Prospective randomized double-blind trial of bilateral thalamic deep brain stimulation in adults with Tourette syndrome. J Neurosurg2007;107:1004-1014

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

36

Servello D, Porta M, Sassi M, Brambilla A, Robertson MM. Deep brain stimulation in 18 patients with severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome refractory to treatment: the surgery and stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:136-142

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

37

Jenike MA. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med 2004;350:259-265

Full Text | Web of Science | Medline -

38

Rappley MD. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N Engl J Med 2005;352:165-173

Full Text | Web of Science | Medline -

39

Allen AJ, Kurlan RM, Gilbert DL, et al. Atomoxetine treatment in children and adolescents with ADHD and comorbid tic disorders. Neurology 2005;65:1941-1949

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

40

Moriarty J, Varma AR, Stevens J, Fish M, Trimble MR, Robertson MM. A volumetric MRI study of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Neurology 1997;49:410-415

Web of Science | Medline -

41

Meyer P, Bohnen NI, Minoshima S, et al. Striatal presynaptic monoaminergic vesicles are not increased in Tourette's syndrome. Neurology 1999;53:371-374

Web of Science | Medline -

42

Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Wernette K, et al. Striatal [11C]dihydrotetrabenazine and [11C]methylphenidate binding in Tourette syndrome. Neurology 2009;72:1390-1396

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

43

Walkup JT, LaBuda MC, Singer HS, Brown J, Riddle MA, Hurko O. Family study and segregation analysis of Tourette syndrome: evidence for a mixed model of inheritance. Am J Hum Genet 1996;59:684-693

Web of Science | Medline -

44

Kurlan R, Eapen V, Stern J, McDermott MP, Robertson MM. Bilineal transmission in Tourette's syndrome families. Neurology 1994;44:2336-2342

Web of Science | Medline -

45

Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O'Roak BJ, et al. Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette's syndrome. Science 2005;310:317-320

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

46

Ercan-Sencicek AG, Stillman AA, Ghosh AK, et al. L-Histidine decarboxylase and Tourette's syndrome. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1901-1908

Full Text | Web of Science | Medline -

47

Sundaram SK, Huq AM, Wilson BJ, Chugani HT. Tourette syndrome is associated with recurrent exonic copy number variants. Neurology 2010;74:1583-1590

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

48

Scharf JM, Mathews C. Copy number variation in Tourette syndrome: another case of neurodevelopmental generalist genes? Neurology 2010;74:1564-1565

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline -

49

Kurlan R, Johnson D, Kaplan EL, Tourette Syndrome Study Group. Streptococcal infection and exacerbations of childhood tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a prospective blinded cohort study. Pediatrics 2008;121:1188-1197

CrossRef | Web of Science | Medline

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢