[節錄]

Summary points

- Recurrent urinary tract infection is common in otherwise healthy women

- Use of products containing spermicide and sexual intercourse increase the risk of recurrences

- No studies have shown that hygiene, direction of wiping, or tightness of clothing increase the risk of recurrence

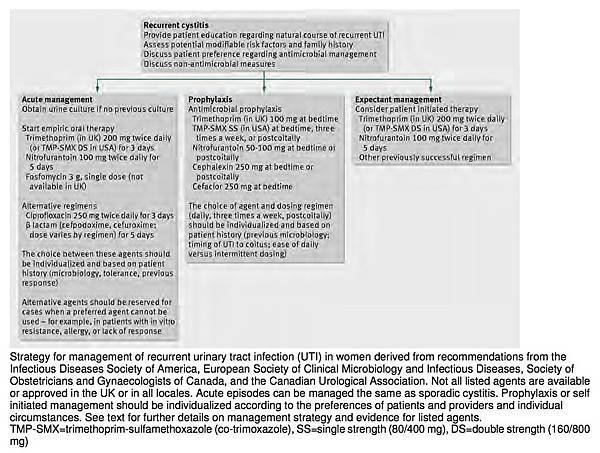

- Management can include self initiated antibiotics for each episode but depends on good communication between patient and physician

- Recurrences can be prevented with regular low dose antibiotics. The choice and dose of antibiotic should be decided on the basis of previous infections and local microbiological guidance and availability of antibiotics

- Non-antimicrobial prevention strategies are promising but have not yet been shown to be as effective as antimicrobial prophylaxis

Recurrent acute cystitis, or recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI), is common in women, and most primary care providers will encounter this clinical entity many times in their practice. Women who have two or more infections in six months or three or more in one year meet the traditional definition of recurrent UTI that has been used for studies on prophylaxis, risk factors, and self initiated management. However, from a clinical perspective, any second episode of UTI warrants consideration as a recurrence and requires an informed approach to diagnosis and management. Most of these recurrences are considered to be reinfections rather than relapse or failure of initial therapy, although reinfection with the same strain can occur. Modifiable risk factors are few, and retrospective case-control observational studies indicate that genetic predisposition may play a role.

How common is recurrent UTI?

Acute uncomplicated cystitis occurs in 50-80% of women in the general population. Natural history studies show that 30-44% of women who have an episode of acute cystitis will have a recurrence, often within three months. Observational cohort studies have found a recurrence rate of 0.3-7.6 infections per patient per year, with an average rate of 2.6 infections per year. Another recurrence will occur in 50% of women who have had two episodes of cystitis in six months. Multiple recurrences often follow an initial infection, resulting in clustering of episodes.

Which women are at risk of recurrent UTI?

The identification of risk factors can help pinpoint modifiable factors amenable to a disease prevention strategy. Known risk factors for recurrence in premenopausal women include the use of spermicidal products and being sexually active. In a well powered case-control study, women aged 18-30 years, without known abnormalities of the urinary tract, who had experienced more than three UTIs in the past year or more than two in the past six months were compared with women without UTI in the past year and no history of recurrent UTI. Women reporting recurrent UTI were 10 times more likely to have had sexual intercourse more than nine times a month in the previous year, and almost twice as likely to have used a spermicide in the previous year than control women. Having a new sexual partner was also an independent risk factor for recurrence.

Factors that were not correlated with recurrence included postcoital voiding, douching, caffeine intake, history of chronic disease or sexually transmitted disease, body mass index, wearing cotton underwear, and taking bubble baths. Also of note, behavioral factors such as voiding after intercourse and increased fluid consumption did not protect against recurrence. However, these risk factors have not been robustly evaluated, and many experts recommend postcoital voiding because it removes uropathogens from the urethra and is a low risk practice.

When should you consider underlying urinary tract disease in recurrent UTI?

Clinical factors that may be indications for further investigation, including imaging and referral, are outlined by the Canadian urological guidelines. The guidelines recommend further evaluation of recurrent disease in women with a history of urinary tract surgery, known anatomical abnormalities, immunocompromise, calculi, urea splitting or multidrug resistant organisms, documented abnormalities of flow, pneumaturia, fecaluria, or persistent gross hematuria or asymptomatic microscopic hematuria after treatment of acute cystitis. Again, these recommendations are mainly based on expert opinion.

Clinically, if recurrence occurs within two weeks of a previous episode, it is classified as a relapse, which suggests failure of the initial therapy, either because of antimicrobial failure or a persisting nidus of infection. A urine culture should be performed in these patients to show that the drug was active against the uropathogen. Further referral or imaging should be considered if the woman meets any of the criteria above or if there is clinical deterioration.

Which organisms are responsible for recurrent UTI?

The pathogenesis of recurrent UTI is similar to that of sporadic infection, and 68-77% of recurrences caused by E coli involve strains genetically indistinguishable from those that caused previous infections. Prospective studies have shown that the same E coli strain can cause recurrence one to three years later, even with negative urine cultures in between the initial infection and the recurrence. This finding supports the idea of a vaginal or rectal reservoir for the causative organisms, with recurrence occurring when the uropathogen from the intestinal flora colonizes the periurethral area and ascends into the bladder. An alternative and more recent hypothesis stemming from animal experiments is that bacteria invade and persist within the bladder epithelium and cause recurrences by re-emerging into the bladder. Intracellular niches of infecting organisms within the bladder epithelium have been shown in mouse models of UTI, but the importance of this phenomenon in humans is unclear. This concept raises the question of whether characteristics of the bacterial strain itself, such as propensity for cellular invasion, predispose the host to recurrent disease.

How do you diagnose recurrent UTI and confirm the diagnosis?

The clinical presentation of recurrent UTI is the same as for sporadic acute cystitis. Local genitourinary symptoms of dysuria, frequency, and urgency or hesitancy come on suddenly. Gross hematuria and suprapubic pain may also be present as part of uncomplicated cystitis. The symptoms are often the same as in previous episodes; ambulatory women with recurrent, uncomplicated UTI have a high accuracy of correct self diagnosis.

Although a urine culture is not usually needed to diagnose sporadic cystitis, expert opinion suggests that urine culture is useful in women presenting with recurrent disease, particularly if no culture was obtained previously. The purpose of the urine culture is to confirm the diagnosis and direct antimicrobial therapy. This is important in recurrent disease to distinguish infection from overactive bladder or interstitial cystitis, both of which can present with urgency and bladder discomfort. In observational studies of recurrent disease, E coli still predominates, but the likelihood of a resistant uropathogen or a non-E coli pathogen is increased. Future episodes can be managed without urine cultures if they respond well to empiric regimens. As outlined above, observational studies show that radiographic imaging is rarely useful, but computed tomography or ultrasound can be considered if a nidus (such as a stone) of infection is suspected.

Is duration of treatment for recurrent UTI the same as for uncomplicated sporadic disease?

Most recurrences can be treated for the same short duration as for standard acute cystitis, although few studies are available to guide duration of therapy in women with diabetes. The argument for treating these women for seven days is that data from observational studies indicate that they are at a higher risk of complications, such as pyelonephritis. However, it is unclear whether longer treatment courses decrease this risk. In the absence of specific evidence regarding optimal duration of therapy in these women, a three to seven day course is reasonable, depending in part on any urological sequelae of the diabetes, such as neurogenic bladder.

In addition to antimicrobial treatment, patients with recurrent UTI should be educated about modifiable risk factors, such as avoiding the use of a diaphragm and of spermicides, including spermicidal condoms, for contraception. The possibility of future recurrences should be discussed in the context of choosing a preventive strategy that best suits the individual woman.

What preventive measures exist for recurrent UTI?

The diversity of effective strategies to prevent recurrences makes a patient centered approach possible. The main decision is whether to use antimicrobial prophylaxis or patient initiated therapy. The second approach is not truly a preventive one but offers the advantages of minimizing antibiotic exposure while giving the patient a high level of control over recurrences. In patient initiated therapy, the physician provides the woman with a course of antibiotics so that she can start therapy if symptoms of UTI develop. She should be counseled to seek care if her symptoms are different from previous episodes, if her symptoms do not resolve with therapy or worsen while on therapy, or if the diagnosis or adherence to birth control methods is in doubt. This approach has been shown to be safe and effective in longitudinal observational studies and offers many potential advantages for women who have few recurrences, such as reduced use of antibiotics, increased convenience, and reduced overall costs.

What is the best prophylactic antimicrobial approach to recurrent UTI?

Antimicrobial prophylaxis involves giving a low dose of antibiotic postcoitally, three times a week, or daily, depending on whether the patient can temporally relate recurrences to sexual intercourse. This strategy can be antibiotic sparing if sexual intercourse is infrequent and antibiotics are given only postcoitally. Typically, prophylaxis is used for six months and then stopped. If the frequency of recurrences returns to the preprophylaxis level, a longer duration of prophylaxis can be given. More than 10 randomized clinical trials have shown low dose antibiotic prophylaxis to be highly effective for the duration of antibiotic use compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of seven clinical trials found an 85% reduced risk of recurrences compared with placebo, and the number of women needed to treat for benefit was 2.2. The choice of antimicrobial agent should be guided by the patient’s microbiological history and drug tolerance, cost to the patient, and the aim of minimizing effects on the intestinal flora. Randomized trials have compared nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim, cinoxacin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Although one trial showed benefit of nitrofurantoin 100 mg daily over trimethoprim 100 mg daily (relative risk 3.58, 1.33 to 9.66), no antibiotic class is clearly favored for prophylaxis on the basis of randomized comparisons and meta-analyses. In another randomized trial, no significant difference in the rate of recurrences was seen for 125 mg of postcoital ciprofloxacin compared with 125 mg of daily ciprofloxacin, suggesting that postcoital dosing was as effective as daily dosing.

The most common adverse events were nausea and candidiasis. Importantly, years of daily use of nitrofurantoin can cause pulmonary toxicity, even at the lower doses used for prophylaxis; whether intermittent regimens for shorter periods result in pulmonary toxicity is unknown. Fortunately, reports suggest that pulmonary toxicity reverses on discontinuation of nitrofurantoin.

What are the nonantibiotic options for prevention in recurrent UTI?

Nonantimicrobial prevention strategies include use of vaginal probiotics, use of cranberry products, and estrogen repletion. A recent Cochrane review of 24 clinical trials, including 14 published since 2008, concluded that cranberry products do not offer significant protection (relative risk 0.74, 0.42 to 1.31) from recurrences, whereas another meta-analysis found that the number of events halved (0.53, 0.33 to 0.83). The potential benefit of cranberry in terms of product type (solid v liquid), dosing, and optimal patient population therefore remains to be elucidated. Oral lactobacillus was inferior to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis in a placebo controlled randomized trial in terms of time to recurrence, but antimicrobial resistance occurred more often in the antibiotic group. However, vaginal lactobacilli suppositories were superior to placebo at preventing recurrences. Oral estrogens do not have a role in prevention, particularly given their potentially harmful systemic effects, but vaginal estrogens show promise in postmenopausal women. A randomized placebo controlled trial in 93 women of eight months of vaginal estrogen cream reported 0.5 recurrences per patient year in the estrogen group versus 5.9 per patient year in the placebo group (P<0.001). A trial of an estrogen releasing vaginal ring (Estring) versus control in 103 women over 36 weeks found a significantly delayed time to first recurrence in the vaginal ring group (P=0.008). By contrast, a trial of estrogen vaginal pessaries versus nitrofurantoin in 171 women found a higher incidence of symptomatic UTI in the estrogen group. Adverse events associated with vaginal estrogen creams include itching, burning, and occasional blood spotting.

Does treating asymptomatic bacteriuria help prevent recurrent UTI?

Convincing evidence from one or more well conducted randomized trials shows that screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic bacteriuria does not prevent symptomatic disease in premenopausal nonpregnant women, women with diabetes, and other populations not covered in this review. Women with asymptomatic bacteriuria are at higher risk of recurrent UTI, but treating the bacteriuria leads to antimicrobial resistance without preventing recurrences. Observational cohort studies from as far back as the 1970s, and a randomized uncontrolled study in the past year, suggest that treating asymptomatic bacteriuria may predispose women to a recurrence of cystitis. In fact, any antimicrobial exposure may increase the risk of acute cystitis by altering the normal vaginal flora.

[Link to free full-text BMJ Clinical Review article PDF with references]

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢