N Engl J Med 2004; 350:1111-1117March 11, 2004DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp022558

也可以順便參考這篇:

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the author's clinical recommendations.

A 30-year-old white woman has a 72-hour history of a pruritic rash on her arms and chest. This is the third episode of the rash this summer, and each episode began in the evening after she had spent less than 30 minutes by a swimming pool in the morning. She has no history of sensitivity to sunlight and is taking no medications. Both the rash and the pruritus are improving, but she still has discomfort. How should this woman be evaluated and treated?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Photosensitivity can be defined by the development of a rash, an exacerbation of an existing rash, an exaggerated sunburn, or symptoms such as pruritus or paresthesias after exposure to sunlight or an artificial source of light. Photosensitivity is common and probably affects members of all racial and ethnic groups, although there have been no studies of its prevalence in the general population. Polymorphous light eruption is the most common form of photosensitivity and probably accounts for more than 90 percent of all cases. This condition was found to have a prevalence of 10 percent in a survey of 271 apparently healthy people in Boston1 and in other studies was diagnosed in 21 percent of 397 people in Sweden,2 14 percent of 182 in London,3 and 5 percent of 172 in Perth, Australia.3

There is a broad spectrum of degrees of photosensitivity among people in whom polymorphous light eruption develops. Those who have a low threshold for the condition can tolerate only minutes of exposure, whereas many people have a high threshold and require prolonged exposure to sunlight before the reaction develops. People who have a mild form of the disease often do not consult a physician or see a primary care physician rather than a dermatologist.3 Polymorphous light eruption is a recurrent condition that persists for many years in most patients.4 Other types of photosensitivity are much less common, but most of them are associated with serious disability either because of their chronic nature or because of their severity and are more likely than polymorphous light eruption to bring the patient to a physician.

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

Differential Diagnosis and Management

Most cases of photosensitivity develop after exposure to sunlight. Because exposure to sunlight is typically associated with exposure to other agents capable of causing a rash, other causes of what appears to be photosensitivity must be considered. Insect bites may be confined to exposed skin, but the central punctum suggests the diagnosis. Plants may cause a contact dermatitis, but the eruption is asymmetric and localized. Sunscreens and airborne allergens may be a cause of eczema and should therefore be considered in the diagnosis of photosensitive eczema.

With regard to reactions that clearly follow exposure to sunlight or to an indoor source of light such as a tanning lamp, the first question is whether the reaction is acute or chronic. Acute reactions are frequently episodic and usually follow a specific exposure to light. Each episode has a defined course that lasts hours, days, or one week or more, and the patient has no symptoms between episodes. Chronic photosensitivity may be manifested as a reaction that lasts through the summer months only or that persists year-round; the severity of the reaction often bears little relation to the particular exposure to sunlight.

Acute Photosensitivity

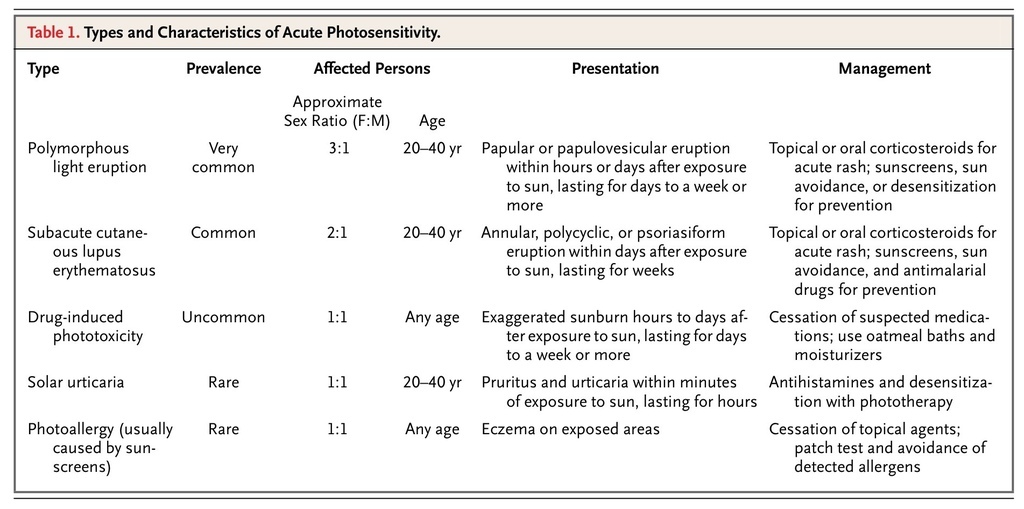

Polymorphous light eruption is the most common cause of acute or episodic photosensitivity. Lupus erythematosus and drug reactions are less common but important causes. The discussion here is focused on these three conditions. The types and characteristics of acute photosensitivity are noted in Table 1

TABLE 1

Types and Characteristics of Acute Photosensitivity.

.

Polymorphous light eruption usually begins in the first three decades of life and occurs more commonly in women than in men. The rash develops within hours to a day or more after a specific exposure to sunlight and lasts for several days to a week or more; in some cases, multiple exposures are required to elicit the rash. Frequently, the rash appears in the spring, and episodes become less marked or cease altogether toward the end of summer. The exceptions to this are severe cases, in which episodes may occur at any time of the year, and cases in people who vacation in a sunny climate during the winter. The rash typically involves the V of the neck and the arms, legs, or both. The hands and face, which are exposed to sunlight in both summer and winter, tend to be spared. Ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation is the most common cause of the reaction, although in a minority of cases the reaction is induced by ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation or by a combination of UVA and UVB radiation.

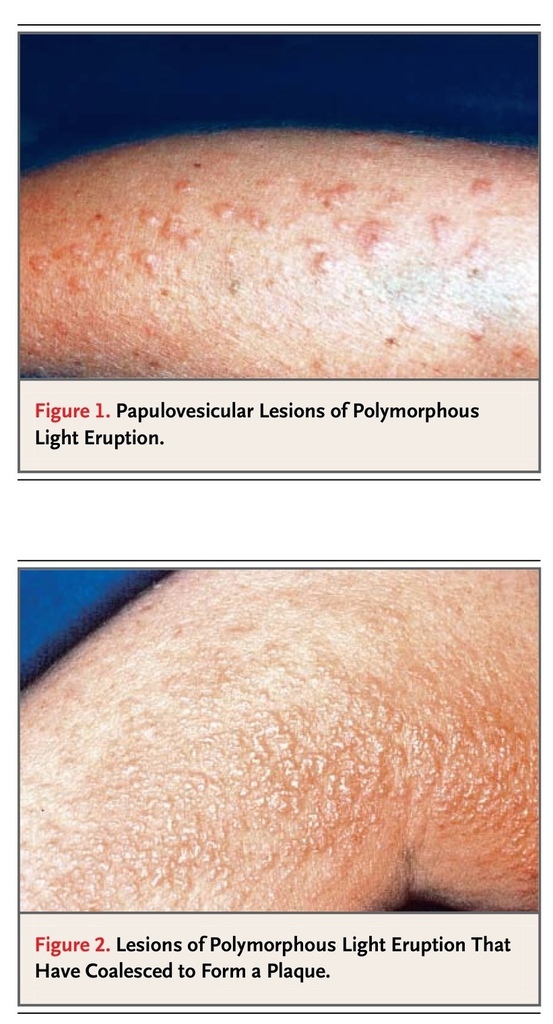

The appearance of the eruption varies from person to person but is consistent in a given patient. Erythematous papules, with or without vesicles, are most common (Figure 1

FIGURE 1

Papulovesicular Lesions of Polymorphous Light Eruption.

). Individual lesions are usually separated by normal skin, but when the condition is severe, lesions may coalesce to form plaques (Figure 2

FIGURE 2

Lesions of Polymorphous Light Eruption That Have Coalesced to Form a Plaque.

).5 Variants that resemble insect bites, bullae, or eczema occur rarely. Pruritus is usually marked. Other features of polymorphous light eruption are also generally consistent in a given patient, including the duration of exposure to sunlight that is required to precipitate the rash, the interval between the exposure and the onset of the rash, and the distribution and duration of the rash.

Most cases of polymorphous light eruption can be diagnosed with reasonable confidence on the basis of the patient's history, but the rash should also be evaluated. The patient should be advised to expose an affected area of skin to sunlight for a sufficient period of time before the medical evaluation in order to elicit the eruption. If the morphologic features of the rash are not the typical papules and papulovesicles of the common form of polymorphous light eruption, the results of a punch biopsy may be suggestive of the condition, although such findings are not diagnostic.6 In patients who have systemic symptoms that are suggestive of connective-tissue disease, an atypical history, or a rash with atypical morphologic or histologic features, further investigation is required, in particular to rule out the possibility of lupus erythematosus.

The management of polymorphous light eruption is aimed mainly at prevention. Largely on the basis of clinical experience, physicians should advise patients who have mild disease induced by prolonged exposure to sunlight to adopt a program of sun avoidance that consists of three components: avoiding exposure that is likely to trigger the eruption, wearing tightly woven clothing and a hat to protect the skin, and using a broad-spectrum sunscreen that blocks both UVA and UVB radiation and has a sun-protection factor of 15 or higher. The most effective sunscreens contain avobenzone and titanium dioxide.7 The sunscreen should be applied to all exposed areas 30 minutes before the patient goes outside and should be water-resistant if swimming or vigorous exercise that is likely to cause perspiration is planned. These measures will prevent the reaction in most patients.

Patients in whom the disease is triggered by a brief exposure to sunlight can be desensitized in the spring with the use of various types of phototherapy, and the nonreactive state can be maintained throughout the summer by means of a weekly regimen of one hour of unprotected exposure to sunlight. A four-week course of treatment with psoralen and UVA radiation or a course of narrowband UVB radiation three times a week provided complete protection in about 90 percent of patients in several observational studies.8-11 In another study, broad-band UVB phototherapy given in a regimen of three exposures a week for five weeks completely protected about 80 percent of patients.12 These treatments may induce the rash or erythema but have no major adverse effects. They are usually regarded as medically necessary treatments. Chloroquine and beta carotene have been used for prophylaxis but were not effective in controlled studies.13

Acute episodes of polymorphous light eruption that are triggered by exposure to sunlight or by phototherapy respond rapidly to corticosteroids. If the eruption is mild and causes limited disability, the application of a topical corticosteroid preparation such as fluocinonide cream (0.05 percent) twice daily typically results in resolution of the rash within three to four days, although this therapy is based on my own observation and has not been studied formally. If the eruption causes substantial disability, a course of prednisone (at a dose of 30 mg daily for five to seven days) may be effective. In a small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, prednisone given at a dose of 30 mg daily cleared the rash in an average of 4.2 days without clinically significant adverse effects, whereas in the placebo group, the rash resolved in an average of 7.8 days.14

The development or exacerbation of a rash after exposure to sunlight is common in patients who have systemic lupus erythematosus. The rash is usually chronic and is frequently associated with malar dermatitis and systemic symptoms such as arthritis, so it is seldom confused with an acute photosensitivity reaction such as polymorphous light eruption. However, patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a variant of lupus erythematosus, may present with episodic photosensitivity, and the condition may therefore be confused with polymorphous light eruption. Both conditions are more common in women than in men. Like polymorphous light eruption, the rash associated with subacute cutaneous lupus may directly follow exposure to sunlight and commonly involves the V of the neck and exterior surfaces of the forearms while sparing the face.

Several features distinguish these two conditions. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus persists longer than a week; the lesions are typically annular, form multiple circles, or resemble psoriatic lesions; and systemic symptoms such as arthralgia and arthritis are common. If this diagnosis is considered, histologic examination of a specimen obtained by punch biopsy of a lesion is a first step, and the findings are usually diagnostic. Serologic testing for antinuclear and anti-Ro (SS-A) antibodies is also warranted. Up to 70 percent of patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus have these antibodies, whereas in a normal population, 10 percent may have a positive test for antinuclear antibody, but less than 0.5 percent have a positive test for anti-Ro antibody.15 This type of photosensitivity is usually alleviated by systemic agents, such as corticosteroids and antimalarial agents, which are used to treat lupus erythematosus, but it may persist. A program of sun avoidance like that used for the management of polymorphous light eruption is also recommended.

The most common form of drug-induced photosensitivity is manifested as an exaggerated sunburn in a patient who is taking an implicated medication or who has taken such a medication in the previous few days. The reaction commences hours to days after exposure to sunlight, lasts days to a week or more, is dose-related, and is most common in patients who have been exposed to high doses of both the drug and sunlight. Susceptibility is also influenced by individual variations in drug absorption and metabolism, as well as skin phototype, with fair-skinned patients being most susceptible.16 The mechanism involves a direct interaction between the drug or a metabolite and UVA radiation to the skin.

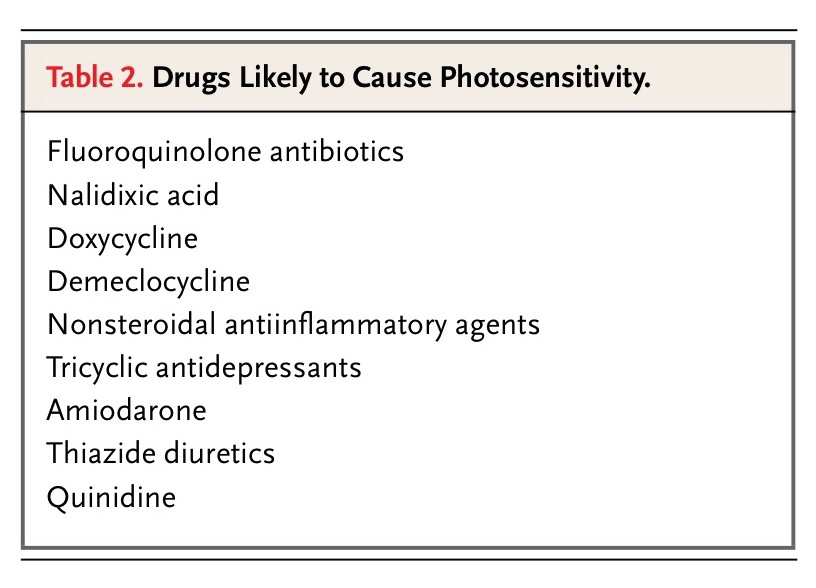

A major problem is identifying the drugs associated with a substantial risk of increased sensitivity to sunlight. Observations in clinical trials and post-marketing reports by physicians have led to the suspicion that many drugs are photosensitizers — one study listed over 200 such drugs.17 On the basis of published data from in vitro and in vivo studies, the number of drugs that have been established as photosensitizing appears to be fairly small (Table 2

TABLE 2

Drugs Likely to Cause Photosensitivity.

). Fluoroquinolone antibiotics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, and tricyclic antidepressants are listed as groups, because most compounds in these groups have been reported to be photosensitizers and market share may determine the frequency of reactions. Of these three groups, the fluoroquinolone antibiotics appear to be the most potent photosensitizers, but published data are lacking on the relative photosensitizing effects of different drug classes or specific agents.18 Drugs such as minocycline, tetracycline, and the sulfonamides (not included in Table 2) have been considered to be photosensitizers17 but appear to be, at most, weak ones, considering their widespread use and the few reports clearly documenting associated photosensitivity.

Patients taking medications that are likely to cause photosensitivity should minimize their exposure to sunlight and use broad-spectrum sunscreens and protective clothing. Once-a-day medications should be taken in the evening. For example, normal subjects who received an evening dose (400 mg) of the fluoroquinolone lomefloxacin were not photosensitive when they were tested 16 hours afterward; a single evening dose is the advised schedule of dosing for this drug.19

Chronic Photosensitivity

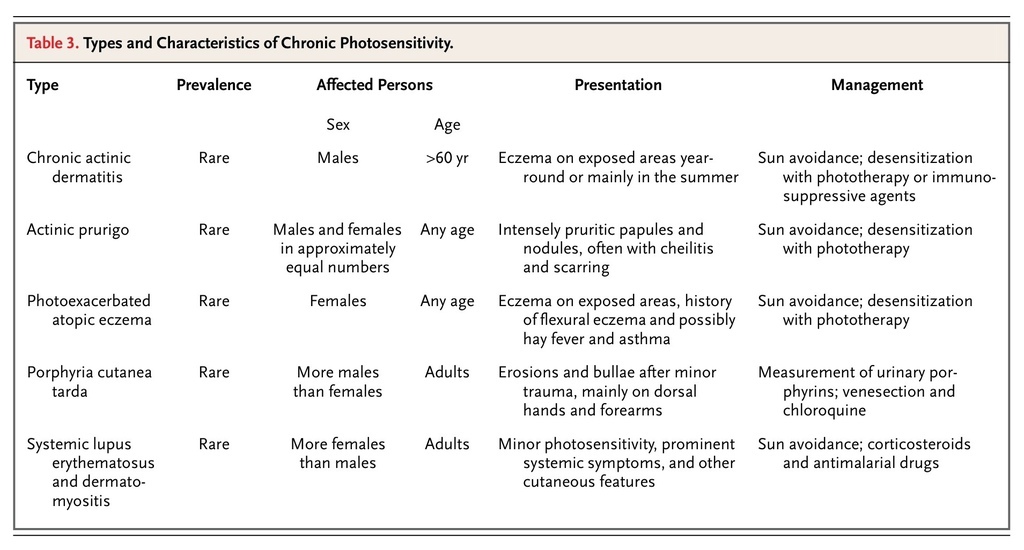

Chronic photosensitivity appears to be much less common than acute photosensitivity. However, its prevalence is uncertain, and it is probably underdiagnosed, because patients are often unaware that a skin eruption is caused by exposure to sunlight. Usually, the eruption is present year-round, but sometimes it is present only in warm months. Exposure to sunlight may exacerbate the eruption or may produce little change. The key point in the diagnosis is that the rash is mainly confined to exposed skin, and this point may be appreciated only on whole-body skin examination. Frequent causes and characteristics of chronic photosensitivity are listed in Table 3

TABLE 3

Types and Characteristics of Chronic Photosensitivity.

. The most common cause is chronic actinic dermatitis.

Chronic actinic dermatitis mainly affects men over the age of 60 years, but it can occur at younger ages and in women.20 The patient presents with an intensely pruritic, indurated, and lichenified eczema involving all exposed areas, with a sharp border where clothing begins (Figure 3A

FIGURE 3

Chronic Actinic Dermatitis.

and Figure 3B). The V and nape of the neck, face, forearms, and dorsal surfaces of the hands are typically affected.

This condition may have multiple causes. It may occur after acute photoallergic reactions to topically applied chemicals or evolve from a nonspecific eczema, and it can be associated with positive contact and photocontact patch-test reactions to plant allergens.21 Photocontact reactions are elicited by applying the chemical allergen to the skin and then exposing the skin to UVA radiation.

The first step in establishing a diagnosis is examination of a skin-biopsy specimen, which usually reveals a chronic dermatitis. The presence of photosensitivity is established by phototesting with the use of sources of ultraviolet and visible radiation. The evaluation usually requires consultation with a center that specializes in photosensitivity. (In the United States, such centers are located in a few academic departments of dermatology.) Patients should be tested for contact and photocontact allergy.22 An airborne contact dermatitis to plant oleoresins or sawdust can be clinically identical to photosensitivity and should be ruled out.

Chronic actinic dermatitis is usually characterized by severe pruritus and an intense inflammatory eruption. Avoidance of sunlight and the use of sunscreens and topical corticosteroids are usually of limited benefit. Contact and photocontact allergens, if identified, should be avoided. Several small observational studies have reported that desensitization with the use of psoralen and UVA therapy23 and immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine and azathioprine can control the condition.24,25

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

The prevalence of acute and chronic photosensitivity in the general population remains uncertain, and the degree of physical and social disability these conditions cause is unknown. The management of most forms of photosensitivity is based largely on anecdotal data, and there is a need for randomized, controlled trials of strategies for prevention and treatment. Additional data are also needed for a better assessment of the risks of photosensitivity that are associated with many drugs.

GUIDELINES

There are no formal guidelines for the diagnosis and management of photosensitivity.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In the patient described in the case vignette, the history of the onset of the eruption several hours after exposure to sunlight, the duration of the eruption for three days, its distribution on the arms and chest (sparing other exposed areas), and the history of previous episodes that summer point to a likely diagnosis of polymorphous light eruption. Evidence of a papular or papulovesicular eruption on physical examination would be consistent with the most common form of this condition. If the diagnosis were in doubt, a punch biopsy of a lesion would be warranted, primarily to rule out lupus erythematosus. If there are symptoms or signs suggestive of lupus, anti-Ro antibodies should also be measured.

Treatment of an episode of polymorphous light eruption depends on the degree of disability it is causing. If discomfort is marked, a brief course of an oral corticosteroid administered for five days will provide rapid relief with complete clearance of the eruption. If discomfort is moderate, I typically recommend the use of a topical corticosteroid such as fluocinonide cream (0.05 percent) applied twice daily; in my experience, this is often sufficient.

Prevention of subsequent episodes should be the goal for the management of photosensitivity. Patients like the woman in the vignette should routinely be advised to apply a broad-spectrum sunscreen 30 minutes before an exposure that is likely to trigger the eruption. If this strategy is not successful, a brief course of narrowband UVB phototherapy in the spring should be an effective preventive measure. Tolerance of sunlight can then be maintained through the summer by regular weekly exposure to sunlight. The course of phototherapy will probably need to be repeated every spring, because spontaneous remissions of polymorphous light eruption are uncommon.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢