fda表示,應該減少運用長效型的β2-agonists來治療氣喘

Long-acting β2-adrenergic agonists (LABAs) have a favorable risk:benefit ratio in asthma therapy only for those patients whose disease is inadequately controlled by asthma-controller medications, FDA officials announced February 18.

The agency wants health care professionals whose asthma patients use a LABA inhalation product and are stabilized to try to discontinue the LABA and control the disease with other medications, FDA’s John K. Jenkins, a pulmonologist, said during a media briefing.

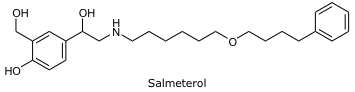

Patients with asthma who use a LABA have an increased risk for severe exacerbation of the disease’s symptoms, FDA concluded after analyzing the Salmeterol

Multicenter Asthma Research Trial and a surveillance study of U.K. salmeterol users and conducting a meta-analysis of 110 studies.

This severe exacerbation of symptoms, FDA said, leads to hospitalization and, in some patients, death.

But all that information came from studies that compared a LABA- containing regimen with regimens lacking a LABA.

The LABAs in the studies were GlaxoSmithKline’s salmeterol, with or without a corticosteroid; Novartis’s formoterol; and AstraZeneca’s formoterol with a corticosteroid.

FDA admitted it does not have enough data to conclude whether the use of a LABA with an inhaled corticosteroid reduces or eliminates the risk of asthma-related hospitalizations and death.

To get that data, FDA said it will require the manufacturers of LABA-containing products to conduct studies evaluating the safety of the drug when used with an inhaled corticosteroid.

The recommendation to decrease the use of LABAs in asthma patients departs from current guidelines, said Janet Woodcock, director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

"A LABA is not an asthma-controller medication," she declared.

Guidelines released in 2007 by the federally sponsored National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) state that LABAs, if prescribed, are to be used in combination with inhaled corticosteroids for the long-term control and prevention of symptoms in patients age 5 years or older presenting with moderate or severe persistent asthma.

Initial maintenance therapy of mild persistent asthma should consist of a low daily dose of an inhaled corticosteroid. To step up therapy in adolescents and adults to what NAEPP calls step 3, add a LABA or increase the inhaled corticosteroid dosage to medium.

Christie Robinson, a specialist in asthma and drug information at the University of California in San Francisco, said FDA’s recommendation to step up therapy to medium-dosage inhaled corticosteroid therapy rather than add a LABA "seems reasonable" given the evidence available to the agency.

The adverse effects typically associated with a medium daily dose of inhaled corticosteroid therapy, she said, are similar to those of a low daily dose.

But the evidence, both in the literature and in her practice at Saint Anthony Free Medical Clinic, have convinced Robinson that patients benefit more from the addition of a LABA than an increase in inhaled corticosteroid.

Still, there is the concern that LABAs can mask the symptoms of an upcoming exacerbation of asthma, she said.

"We won’t jump to [salmeterol–fluticasone] as often when we get to step 3 for adults," she said a week after FDA’s announcement.

Instead, she may consider first increasing the dose of inhaled beclomethasone to see if medium-dosage inhaled corticosteroid therapy manages the patient’s asthma.

"But I won’t be afraid to add a long-acting β-agonist on to that medium-dose steroid once we’re getting to step 4 therapy because the studies have shown such a benefit for these patients in terms of their symptom management, improvements of quality-of-life factors," Robinson said.

Theresa Prosser, a professor at the St. Louis College of Pharmacy who is an expert in pulmonary disease, said FDA’s recommendation is not really at odds with NAEPP’s guidelines.

The guidelines’ stepwise approach to managing asthma advises "stepping down, if possible, if asthma is well controlled for at least three months," she said.

Which therapy to reduce is the decision of the health care professional, Prosser said. In the case of a patient using an inhaled corticosteroid and a LABA, the choices are lower the dosage of the inhaled corticosteroid or stop the LABA.

According to FDA’s Jenkins, health care professionals more commonly try to reduce or eliminate the corticosteroid.

Prosser said earlier versions of the guidelines had advised stepping down therapy if asthma control had been achieved.

But asthma control, until August 2007, had been defined in terms of six goals, including "[m]inimal or no chronic symptoms day or night."

The current guidelines describe nine components of control, most of them in quantitative terms. One of the criteria for well-controlled asthma is symptoms " 2 days/week," for example.

2 days/week," for example.

Unlike diabetes mellitus and hypertension, in which a single measurement indicates whether the disease is well controlled, Prosser said, asthma has multiple elements that must be considered.

Ideally, asthma that is well controlled should not interfere with a patient’s daily activities, she said. "It doesn’t necessarily mean that someone is symptom free."

Prosser said the challenge of getting an asthma patient to the well-controlled stage tempts the clinician to leave things as they are.

Stepping down therapy is possible, she said, because the maintenance of well-controlled asthma requires less medication than the control of a flare-up.

Robinson said it will be challenging to implement FDA’s recommendation to use a LABA for the shortest duration possible.

"When we do add a long-acting β-agonist, it’s with a [product] that already has a corticosteroid," she said. "And it’s not going to be that common, I think, for us to use that short term" and then replace the combination product with a corticosteroid alone.

Prosser, whose clinical practice is at a hospital-based primary care clinic for the uninsured, said FDA’s announcement will make her "more diligent" about finding asthma patients suitable to step down in therapy.

Also, when following the NAEPP guidelines for stepping up therapy from a low daily dose of an inhaled corticosteroid, she will be a little less likely to recommend a LABA–corticosteroid inhaler before finding out whether medium-dosage inhaled corticosteroid therapy helps the patient.

FDA’s additional recommendation that patients in need of a LABA in addition to an inhaled corticosteroid use a combination product addresses a problem with compliance, Prosser and Robinson said.

"Because the long-acting β-agonist tends to control the symptoms, sometimes the patients will stop taking their inhaled steroid" if using separate inhalers, Prosser said. Those patients detect no immediate benefit from the inhaled corticosteroid and then quit using it.

Robinson said compliance with almost any therapy is an issue for her patients, who may be homeless and receive their medications through the city’s safety-net program if uninsured.

None of her patients, she said, have a regimen in which a LABA is the sole maintenance medication.

Prosser said FDA’s announcement reinforces the point that clinicians should regularly assess their asthma patients’ condition, just as they would regularly assess hypertension patients’ blood pressure.

But with asthma patients, she added, once their disease is well controlled, clinicians should consider stepping down therapy in a logical manner—bearing in mind FDA’s preference to eliminate the LABA.

— Cheryl A. Thompson

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢