This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the author's clinical recommendations.

A 20-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with a report of having been sexually assaulted 24 hours earlier. She reports that a man she had met at a campus party walked her to her apartment, where he assaulted and raped her, including vaginal penetration. She did not report the assault to the police but confided in a friend, who encouraged her to seek medical care. How should this patient be evaluated and treated?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Sexual assault is a broad term that includes rape, unwanted genital touching, and even forced viewing of or involvement in pornography. Rape is a legal term and in the United States refers to any penetration of a body orifice (mouth, vagina, or anus) involving force or the threat of force or incapacity (i.e., associated with young or old age, cognitive or physical disability, or drug or alcohol intoxication) and nonconsent. The definition of rape includes spousal rape, although proof of spousal rape often relies more on evidence of force.

Sexual assault is a complex problem, with medical, psychological, and legal aspects. Large population-based surveys indicate a lifetime prevalence of 13 to 39% among women and 3% among men.1,2 These data are most likely an underestimation, because most large studies do not sample vulnerable populations (e.g., homeless, sheltered, or institutionalized persons). Certain populations are at increased risk for sexual assault, including the physically or mentally disabled; homeless persons; persons who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgendered; alcohol and drug users; college students; and persons under the age of 24 years.3-6 Sexual assaults that are facilitated by the use of alcohol and drugs, which in some cases are voluntarily ingested by the victim, are increasingly recognized and are more common than classic forcible assaults among college students.3,7

Only 16 to 38% of rape victims report the rape to law enforcement, and only 17 to 43% present for medical evaluation after rape; one third of victims of rape never report the assault to their primary care doctor.1,2,8,9 Although this review focuses on the evaluation of women, men may also present after sexual assault. Men who report physical injuries may be more hesitant to report the sexual component of an assault.10

Even in the absence of physical injury, which occurs in about half of cases, victims are often frightened, emotionally traumatized, and embarrassed. They often fear that they will not be believed or that information about their rape will be released to the public.1 They may also fear for their safety if they know the assailant or if the assailant has access to their personal information.1,2 Many rape victims doubt that their case will be prosecuted successfully, a fear that is often justified: in the United States, fewer than half of rape cases are successfully prosecuted.11,12

This review addresses the adult patient who is a victim of sexual assault and focuses on short-term care. Care of the sexually abused child differs in many respects, and evaluation in such cases is often referred to practitioners specializing in pediatric child abuse.

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

Rape victims often present to the emergency department but may also present to their primary care physician. If victims present within the time limit for evidence collection and wish to have evidence collected, they should be referred to a local rape treatment center or emergency department, according to local protocol. The time limits for evidence collection depend on the jurisdiction and range from 72 to 120 hours. The evaluation and treatment of sexual assault victims are time-intensive and should optimally be provided by a team that includes an emergency physician or other medical provider overseeing care and treating injuries, a trained sexual assault examiner, and a social worker or rape crisis counselor (who has expertise in acute reactions to rape and can assist in offering support, describing options, and explaining the hospital process). Rape crisis counselors also support family and friends of the victim. In some centers, a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) who has extensive training and experience is responsible for examining the victim for injuries, providing objective documentation, and collecting evidence while maintaining chain of custody and offering support and community referrals. Maintaining chain of custody requires the documentation of the transfer of the evidence kit from the time it is opened until it is sealed and placed in a secure area. Some regions have a sexual assault response team (SART), a coordinated team consisting of representatives from health care, forensics, the local rape crisis center, law enforcement, and the prosecutor's office. There are currently approximately 650 SANE or SART programs in the United States, and these programs have been associated with improved compliance with medical treatment guidelines, increased quality of evidence collection, and an increased likelihood that charges are filed and successfully prosecuted, as compared with routine care.13-17

Evaluation for Acute Traumatic Injuries

General body trauma is reported by up to two thirds of rape victims who present to the emergency department and is more frequent than genital trauma.18,19 Injuries may include attempted strangulation; blunt traumatic injuries to the head, face, torso, or limbs; and penetrating injuries. Defensive injuries, such as lacerations, abrasions, and bruises, may be observed on the hands and the extensor surfaces of the arms and medial thighs. Minor injuries, such as bite marks, may also occur. Injuries should be treated according to established trauma protocols.

Anogenital Injuries

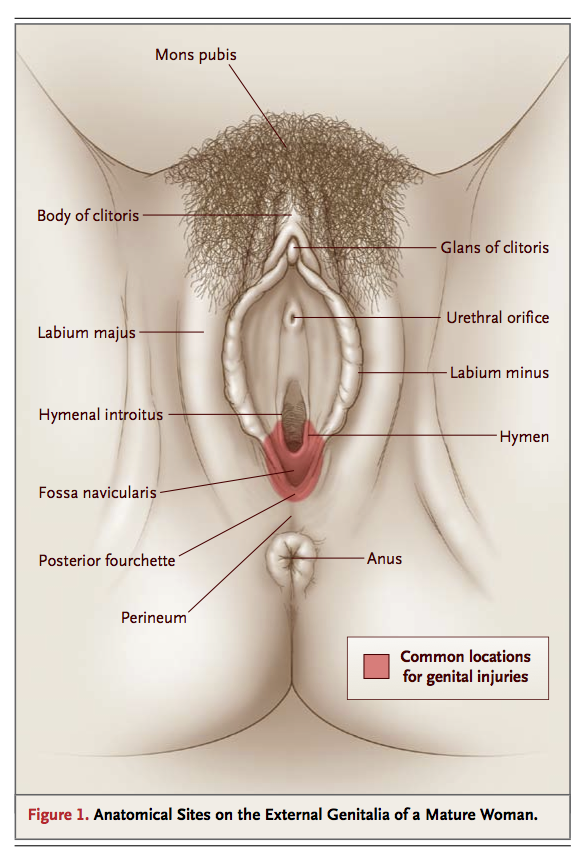

Anogenital injuries are not always seen after sexual assault, and clinicians should understand that the absence of such injuries does not equate with no assault. Although visual inspection alone identifies anogenital injuries in less than half of victims, the use of advanced visualization techniques, such as colposcopy and toluidine blue staining, increases identification rates to 53 to 84%.18-23 Common locations for genital injuries include tears or abrasions of the posterior fourchette (where the two labia minora meet posteriorly), abrasion or bruising of the labia minora and fossa navicularis (directly anterior to the fourchette), and ecchymosis or tears of the hymen (Figure 1

Anatomical Sites on the External Genitalia of a Mature Woman.

).24 The rate of detection of genital injuries varies according to the age of the victim (more common in the young and elderly), virginal status, degree of resistance, time from the assault to examination (more common if the victim is examined within 24 hours), and number of assailants or assaults. Despite the relatively low frequency of obvious injuries, the documentation of such injuries increases the chances of a successful prosecution.25-28

Forensic History and Evidence Collection

Although the acute evaluation and treatment of traumatic injuries take precedence over evidence collection, measures should be taken to facilitate evidence preservation in the trauma room. If the patient is transported from the scene by ambulance, the sheets on which he or she is transported should be preserved and folded in a manner to retain critical evidence, such as foreign fibers and debris. When the removal of the victim's clothes requires cutting, care should be taken not to cut through any existing holes or tears, since these can help corroborate a victim's account. If there are ligatures or ties on the limbs or neck, they should be cut so as to preserve the knot, which may be the signature of a perpetrator. Before a Foley catheter is placed, evidence that may contain DNA can be collected from the vagina or the penis. Photographs of injuries should be taken by the clinician if the management of serious acute injuries precludes the prompt performance of a detailed sexual-assault examination. Performance of these procedures is consistent with recommended SANE protocol and prevents the loss of crucial evidence.

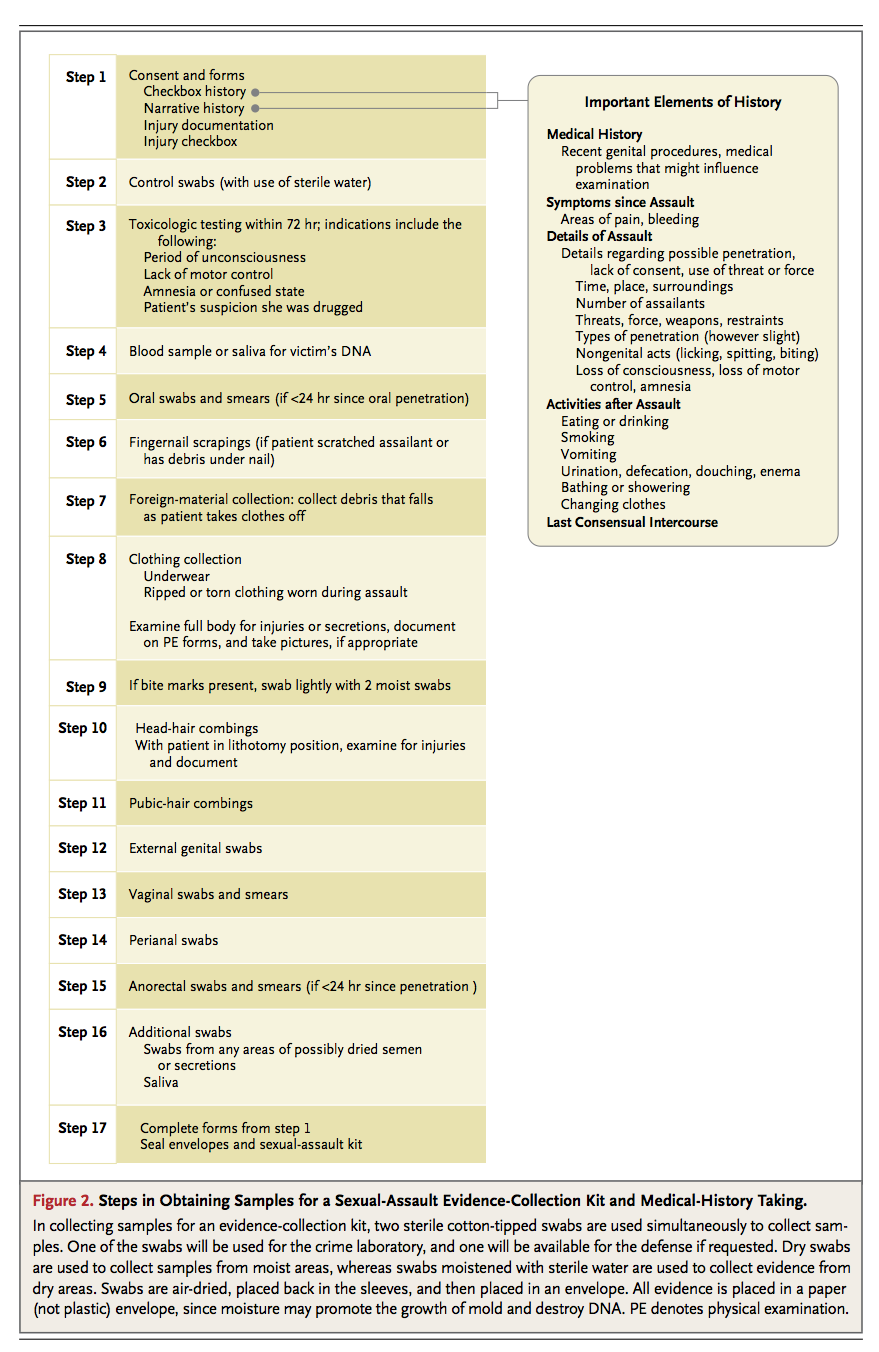

After medical clearance, the patient should be offered evidence collection. The collection of forensic evidence is a multistep process that can take 6 or more hours to complete and is best performed by specially trained personnel. The aim is to record the victim's report of the assault, collect and record evidence to support this report, and collect DNA. Highly sensitive DNA techniques can assist in identifying a perpetrator by matching DNA to the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) database of convicted felons, maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Evidence collection requires the patient's consent during each of the steps. The examiner should take care to explain each step of the examination process and the reasons behind each step. The patient should be given the opportunity to determine the pace of the examination and be reminded of the option of declining any part of the examination.

Standardized evidence-collection kits contain forms for documentation to assist examiners. Figure 2

Steps in Obtaining Samples for a Sexual-Assault Evidence-Collection Kit and Medical-History Taking.

summarizes important historical details to be documented and steps in a sample evidence-collection kit. (Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.)

Medical providers should understand that it is not their responsibility to determine whether a sexual assault has occurred, since such a determination can rarely be made on the basis of examination alone but, rather, will be made in the courtroom when appropriate. In cases of sexual assault that is facilitated by suspected alcohol or drug use, the results of comprehensive toxicology screening can be sent to the crime laboratory. Indications for testing include amnesia, confusion, and loss of motor control. The time limits for testing vary according to jurisdiction (usually, 72 to 96 hours). The patient should understand that such screening will reveal the ingestion of both prescription and nonprescription drugs, results that can be admitted as evidence in court. Blame should not be assigned to the victim, regardless of whether drug or alcohol ingestion was voluntary.

Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections

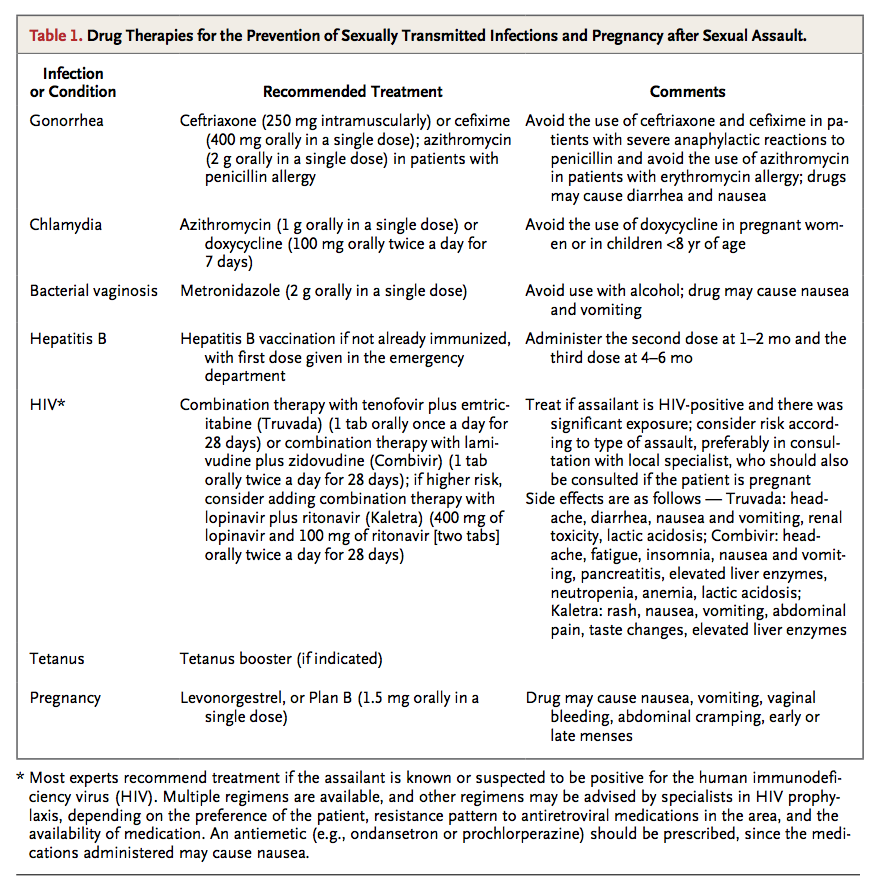

All patients should be offered prophylaxis in the emergency department for sexually transmitted infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published recommendations for treatment to prevent sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, bacterial vaginosis, and hepatitis B (Table 1

Drug Therapies for the Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Pregnancy after Sexual Assault.

). 29 Syphilis is less prevalent, and prophylaxis for gonorrhea may also provide coverage for syphilis. Most experts discourage testing for sexually transmitted infections in the emergency department, unless such testing is clinically indicated by symptoms. One exception is in cases of suspected child sexual abuse, in which a positive result of screening for sexually transmitted infections may be considered proof of abuse. If the assailant is known to be positive for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the CDC also recommends HIV postexposure prophylaxis. The use of postexposure prophylaxis for HIV in other circumstances is discussed below in the Areas of Uncertainty section.

Pregnancy Prevention

The risk of pregnancy after rape is approximately 5%.30 Progestin-only emergency contraception (1.5 mg of levonorgestrel), which is administered as a one-time dose within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse, has been shown to be 98.5% effective in preventing pregnancy. Since efficacy decreases with increasing time since unprotected intercourse, the drug should be taken within 72 hours after an assault. Although this medication should not be given if the person is already pregnant, it does not cause abortion, and there is no evidence that it causes harm to a pregnancy. Side effects include nausea, fatigue, abdominal pain, and vaginal bleeding.31

Crisis Intervention with Emotional Support

There is no normal reaction to rape. Acute reactions range from severe emotional distress to emotional numbing, nervous laughter, anger, and denial. Many victims experience shame, self-blame, and self-doubt. Medical providers should emphasize that the victim is not to blame, no matter what happened before the assault. Longitudinal data indicate that sexual-assault survivors are at increased lifetime risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (30%), major depression (30%), and contemplation of suicide (33%) or an actual attempt (13%).1 Risk factors for PTSD after rape include previous depression, alcohol abuse, and increased severity of injury during the assault.1 Rape survivors are also at increased risk for chronic medical problems, including chronic pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, and functional gastrointestinal disorders.32 Care providers should enlist the input of social workers or rape crisis counselors to help evaluate the patient's immediate and future emotional and safety needs and formulate a plan for safety as the patient is discharged.

Follow-up and Mandatory Reporting

Rape victims should be referred for both medical follow-up (testing for pregnancy, HIV, and hepatitis) and psychiatric support. The patient should be encouraged to follow up with her primary care doctor. Rape crisis centers can provide ongoing support, limited free confidential counseling, and legal services. Some jurisdictions may require mandatory reporting of rape (with identifying information either included or removed) or weapons-related injuries in the competent adult. All jurisdictions require reporting the assault of a child or an elderly or disabled person.33

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

HIV-postexposure prophylaxis may be offered if the patient presents within 72 hours after a sexual assault, but its use is controversial in cases in which the perpetrator is not known or is suspected to be HIV-positive. In the absence of data from randomized trials, evidence for the use of HIV prophylaxis in cases of sexual assault is extrapolated from studies of maternal–fetal transmission and exposure of health care workers. Treatment with antiretroviral agents in these circumstances decreases the rate of transmission of HIV by 70 to 80%.34,35

Although the risk of acquiring HIV from a sexual assault is low, there are case reports of such transmission in the literature.36,37 The exact incidence of HIV transmission after isolated sexual contact with an HIV-positive person is unknown but is estimated to be approximately 1 to 2 cases per 1000 after vaginal penetration and 1 to 3 cases per 100 after anal penetration. The risk increases with a higher stage of HIV infection and a higher viral load in the assailant and with the presence of genital trauma or genital ulcers and coinfections in the victim.38,39 One study reported a prevalence of HIV infection of 1% among incarcerated persons who had been convicted of a sexual offense.40 On the basis of this prevalence and the reported risk of transmission, the estimated risk of transmission is approximately 1 or 2 cases per 100,000 for vaginal assault and 2 or 3 per 10,000 for anal assault (although trauma incurred during the assault may increase the risk).

Currently, the CDC does not have guidelines for HIV prophylaxis in cases of sexual assault when the HIV status of the assailant is unknown, and decisions should be made individually, taking into account the estimated risk of infection in the perpetrator, the nature of the assault, and the preference of the patient. The victim should understand the low risk of transmission, the possible side effects of medication, and the importance of strict adherence to treatment and follow-up, since incomplete treatment is associated with an increased rate of failure of prophylaxis. Rates of follow-up and completion of HIV prophylaxis after sexual assault have been reported to be approximately 18 to 33%.41-43 The decision to initiate prophylaxis should be made in the emergency department, after consultation with a local specialist in HIV prophylaxis if possible, and the patient should be given a medication starter pack pending follow-up in a clinic (Table 1). If there is no local specialist available, 24-hour consultation for providers is available at the National Clinicians' Postexposure Prophylaxis Hotline. (A list of clinical resources is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.) Postexposure HIV prophylaxis was recently reviewed in the Journal.44

The role of different types of psychotherapy in decreasing psychological sequelae of rape remains unclear. Limited data support a potential benefit of the early initiation of cognitive behavioral therapy, which involves education of the patient about normal reactions to assault, relaxation training, recounting of the experience, exposure to feared (but safe) stimuli, and cognitive restructuring.45,46 In one randomized trial, women who were assigned to receive early cognitive behavioral therapy after sexual assault had a significantly greater reduction in self-reported symptoms of PTSD after the intervention than did those receiving only supportive counseling, but differences in outcome were no longer significant at 3 months.45 More data are needed from randomized, controlled trials to assess and compare the effects of various interventions on risks of PTSD, anxiety, and other sequelae of sexual assault.

GUIDELINES

Guidelines for the treatment of patients after sexual assault have been issued by the Department of Justice,47 the American College of Emergency Physicians,48 and the World Health Organization.49 The CDC has published guidelines for treatment after exposure to sexually transmitted infections.29 (See the Supplementary Appendix for links to this guideline and other resources.) The recommendations that are provided in this article are consistent with these guidelines. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all women for a history of sexual assault at every visit and offers tools to assist the practitioner.50

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A patient presenting for care after sexual assault, such as the woman described in the vignette, should first be evaluated for acute traumatic physical injuries. She should then be offered prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy and, if indicated, toxicologic testing to identify drugs that may have been given to incapacitate her. Care should be coordinated by the emergency physician, and the patient should be given emotional support by staff members, a rape crisis counselor or social worker, and (where available) a SANE. The patient should be offered forensic-evidence collection (preferably by a SANE), according to state protocol. Evidence collection is offered in most states even if the patient does not want to immediately report the assault to the police. Staff members should offer to call the police if the victim decides to report the assault. Finally, safe plans for discharge, including planned follow-up for medical care and psychological support, are critical.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢