A 39-year-old woman (gravida 2, para 0) presented to her obstetrician at 32 weeks' gestation with a 2-day history of low back pain. The pain was abrupt in onset and constant. She reported no fever, chills, dysuria, urinary frequency, vaginal discharge or bleeding, or other associated symptoms. Preterm labor was ruled out, and she was advised to rest and take acetaminophen as needed.

All the possible causes of low back pain in women must be considered during pregnancy, along with the additional possibility that the pain may be directly attributable to the pregnancy. Labor is rarely described as abrupt in onset, is usually colicky in nature, and is often associated with other symptoms or signs, such as blood-tinged vaginal discharge. When there is doubt regarding the cause of the pain, observation and serial examinations of the cervix for evidence of change are helpful. Musculoskeletal pain is common, and its likelihood increases as pregnancy advances, owing to weight gain, the loosening of connective tissues with the hormonal changes of pregnancy, and the shift forward in the woman's center of gravity. Pyelonephritis is a concern with an abrupt onset of back pain, but it is unlikely in this patient, given the reported location of the pain and the absence of fever, chills, urinary frequency, and dysuria.

The patient returned to her obstetrician the next day with worsening pain located in the middle-to-lower back, now with radiation to the upper abdomen. She reported an episode of vomiting that morning. She still had no fever, chills, sweats, or urinary symptoms and reported no changes in bowel function and no vaginal bleeding or headache. She was referred to the emergency room for further evaluation.

On physical examination, the blood pressure was 159/91 mm Hg, pulse 95 beats per minute, and temperature 36.6°C (97.9°F). The abdominal examination showed a gravid uterus and epigastric tenderness without rebound or guarding. There was no palpable mass or hepatosplenomegaly and no tenderness at the costovertebral angle.

More information is needed regarding the nature of the pain. Colicky pain could be intestinal, renal, biliary, or uterine in origin. For the first three of these sources, the presentation in a pregnant woman would not be expected to differ from that in a nonpregnant woman. Although uterine contractions are relatively easy to detect, are very common, and occur with increasing frequency as pregnancy progresses, premature labor is notoriously difficult to distinguish from contractions unrelated to labor. Noncolicky pain could reflect an adnexal condition, such as ovarian torsion.

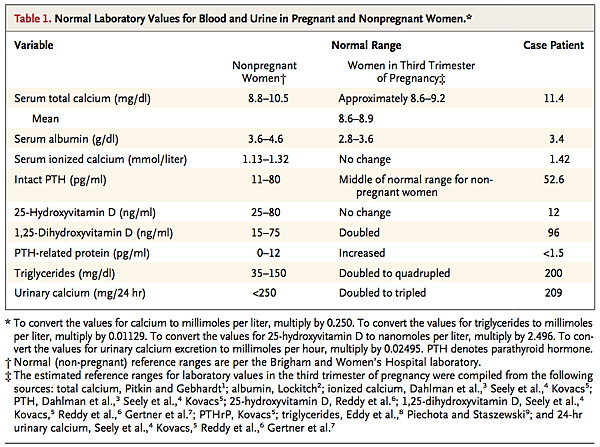

The white-cell count was 11,700 per cubic millimeter, the hematocrit 29.7%, and the platelet count 275,000 per cubic millimeter. The serum level of sodium was 135 mmol per liter, potassium 4.3 mmol per liter, chloride 105 mmol per liter, bicarbonate 21 mmol per liter, creatinine 0.7 mg per deciliter (61.8 μmol per liter), and glucose 70 mg per deciliter (3.9 mmol per liter). The calcium level was 11.4 mg per deciliter (2.8 mmol per liter) (reference range, 8.8 to 10.5 mg per deciliter [2.2 to 2.6 mmol per liter]), and the albumin level 3.4 g per deciliter (reference range, 3.6 to 4.6) (references ranges for calcium and albumin in women in the third trimester of pregnancy are shown in Table 1

Normal Laboratory Values for Blood and Urine in Pregnant and Nonpregnant Women.

). The level of alanine aminotransferase was 18 U per liter (reference range, 7 to 40), aspartate aminotransferase 45 U per liter (reference range, 6 to 40), alkaline phosphatase 159 U per liter (reference range, 27 to 110), total bilirubin 0.3 mg per deciliter (5.1 μmol per liter) (reference range, 0.3 to 1.2 mg per deciliter [5.1 to 20.5 μmol per liter]), amylase 617 U per liter (reference range, 20 to 70), and lipase 1261 U per liter (reference range, 3 to 60). Ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant of the abdomen revealed no evidence of gallstones or cholecystitis. The liver and common and intrahepatic bile ducts appeared normal. The pancreas was obscured by bowel gas.

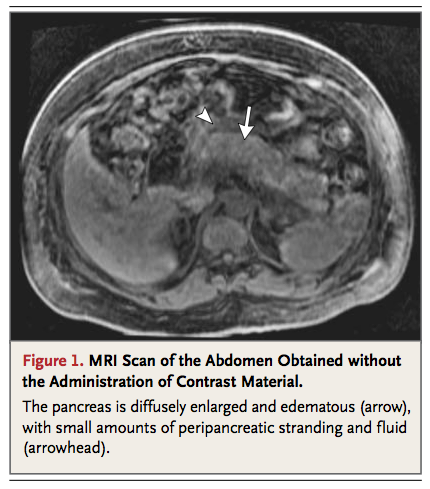

The patient was transferred to a tertiary-care hospital with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. At the time of admission, her blood pressure was 126/80 mm Hg. She was pain-free and drowsy after having received morphine in the emergency room, and her abdomen was not tender. Repeat laboratory testing revealed serum levels of calcium of 11.8 mg per deciliter (3.0 mmol per liter), albumin 3.3 g per deciliter, triglycerides 200 mg per deciliter (2.2 mmol per liter), lipase 2008 U per liter, and amylase 833 U per liter. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen revealed a diffusely enlarged, edematous, heterogeneous-appearing pancreas with small amounts of peripancreatic stranding and fluid, findings that were consistent with acute pancreatitis (Figure 1

MRI Scan of the Abdomen Obtained without the Administration of Contrast Material.

). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a normal-appearing gallbladder and no dilatation of the biliary or pancreatic ducts.

The two most common causes of acute pancreatitis in adults are gallstones and alcoholism. Less common causes include certain drugs (e.g., didanosine and valproic acid), hypertriglyceridemia, hypercalcemia, infection, trauma, ischemia, and conditions causing ampullary obstruction, such as periampullary diverticula or pancreatic or periampullary tumors; there are also rare inherited forms of pancreatitis. Pancreatitis is uncommon in pregnancy, and when it does occur, the cause is most often of biliary origin. Plasma triglyceride levels are increased by a factor of two to four during pregnancy, a change that is inconsequential in most pregnant women but that may result, in the presence of an underlying lipid disorder, in severe hypertriglyceridemia, precipitating pancreatitis; however, the triglyceride level is normal in this patient.

This patient has a high calcium level, which may be the cause of her pancreatitis. This finding is particularly notable because total calcium levels are lower in normal pregnancy than in the nonpregnant state. In contrast, levels of ionized calcium remain unchanged throughout pregnancy. Evaluation is warranted for hyperparathyroidism, since this is the most common cause of hypercalcemia. Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D should also be measured to rule out the possibility of vitamin D intoxication.

The patient's medical history was notable for pregnancy-induced hypertension and anemia, which were diagnosed at approximately 27 weeks' gestation. Four years before presentation she had a kidney stone, which passed spontaneously; stone analysis was not performed. Her medications included methyldopa (250 mg twice daily) and a prenatal vitamin daily. She did not smoke, drank two glasses of wine per week before becoming pregnant and none during pregnancy, and had no history of illicit-drug use. Her family history was notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus in her parents and paternal grandmother, prostate cancer in her father, and breast cancer in two paternal aunts.

The ionized calcium level was 1.42 mmol per liter (reference range, 1.13 to 1.32). The level of intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), measured on the night of admission, when the serum calcium level was 11.1 mg per deciliter (2.8 mmol per liter), was 52.6 pg per milliliter (reference range, 11 to 80). Intravenous hydration was administered, with morphine given as needed for pain control. The next day, the serum calcium level was 10.1 mg per deciliter (2.5 mmol per liter), and the intact PTH level 85.4 pg per milliliter; the phosphorus level was 2.3 mg per deciliter (reference range, 2.4 to 5.0). The thyrotropin level was 1.35 mIU per liter, 25-hydroxyvitamin D 12 ng per milliliter (reference range, 30 to 60), and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 96 pg per milliliter (reference range, 15 to 75).

The laboratory data are consistent with primary hyperparathyroidism. Whereas the initial level of intact PTH was within the normal range, it is high given the elevated calcium level. PTH levels are typically in the low-to-midnormal range during pregnancy. The patient's 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is low, whereas her 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level is elevated. Although an elevated level of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is a recognized cause of hypercalcemia in nonpregnant patients with certain neoplastic or granulomatous disorders (e.g., lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or tuberculosis), in this patient, the elevated level may simply reflect the physiologic increase in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D during pregnancy. Elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels are also observed in hyperparathyroidism as a result of increased conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. This increased conversion might also explain the patient's low level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, although the level is low enough to suggest concomitant vitamin D deficiency. If she has vitamin D deficiency, it could be keeping her serum calcium level less elevated than it otherwise would be. This combination of factors in this patient indicated that caution should be used during vitamin D repletion.

Instructions were given for the patient to receive nothing by mouth, and she was treated with intravenous hydration, furosemide, and nasally administered calcitonin, with improvement in her calcium levels to a range of 1.32 to 1.38 mmol of ionized calcium per liter. Her pain subsided. Levels of amylase and lipase gradually fell. Methyldopa was discontinued, since pancreatitis is a rare side effect of this treatment. Treatment with oral labetalol was started for blood-pressure control. Fetal well-being was monitored by tracking the fetal heart rate, performing daily ultrasound examinations, and checking biophysical profiles, which remained normal.

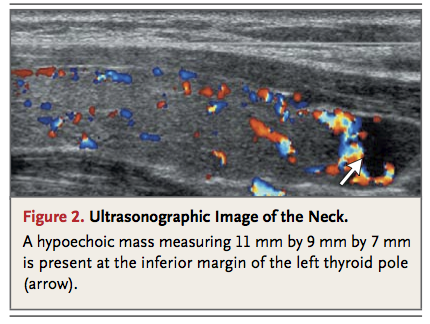

It is likely that the patient's hyperparathyroidism led to her pancreatitis. Her history of nephrolithiasis suggests that hypercalcemia may have been present for years. Although her symptoms have subsided and her calcium levels have improved, she continues to have mild hypercalcemia and is at risk for worsening hypercalcemia and attendant pregnancy-associated complications, including intrauterine growth retardation, preterm delivery, intrauterine fetal death, and neonatal tetany. Consequently, surgery should be considered in this patient. Preoperative imaging for identification and localization of an adenoma will reduce the duration and invasiveness of surgery. Since sestamibi scanning is contraindicated during pregnancy, ultrasonography of the neck would be the preferred imaging technique.

Ultrasonography of the neck revealed a 1.1-cm hypoechoic mass at the inferior margin of the lower pole of the left thyroid (Figure 2

Ultrasonographic Image of the Neck.

). After further abatement of the pancreatitis, when the patient could tolerate oral intake, she underwent parathyroid exploratory surgery and resection of a left lower parathyroid adenoma under general anesthesia, without complications. Blood samples were obtained from the internal jugular vein before and 10 minutes after resection of the adenoma, and analysis showed that the PTH level decreased from 344 to 60.7 pg per milliliter.

The majority of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism are caused by solitary parathyroid adenomas. Intraoperative PTH monitoring takes advantage of the short half-life of PTH in plasma (3 to 4 minutes) and the availability of a rapid assay for PTH. A reduction in PTH levels of more than 50% is considered to be an indicator of successful removal of the adenoma. Postoperative monitoring of this patient's serum calcium levels should be continued.

After resection, the patient's serum calcium levels normalized and remained normal for the duration of her pregnancy. Maintenance doses of 600 mg of calcium carbonate with 200 IU of vitamin D twice daily were prescribed, in addition to 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily. The amylase and lipase levels gradually normalized. The patient remained in the hospital for continued monitoring because of mild preeclampsia. Labor was induced at 37.5 weeks' gestation, after her blood pressure rose further, to 152/104 mm Hg, despite the administration of labetalol. She delivered a healthy girl by means of cesarean section, which was performed because of the failure of labor to progress. The postpartum serum calcium levels remained normal. After a course of 50,000 units of ergocalciferol weekly for 8 weeks, the 25-hydroxyvitamin D level increased to 30 ng per milliliter. The patient had persistent postpartum hypertension, requiring the continuation of antihypertensive therapy, but was otherwise well.

An association between hyperparathyroidism and an increased prevalence of hypertension has been reported in nonpregnant patients, but the mechanism has not been identified. The effects of parathyroidectomy on blood-pressure levels in such patients have been inconsistent.

COMMENTARY

Primary hyperparathyroidism occurs rarely during pregnancy — the true incidence is unknown. Since many cases are asymptomatic, they are not recognized in pregnant patients. In addition, pregnancy is associated with alterations in the levels of calcium and calcitropic hormones such as PTH, which may obscure the hyperparathyroidism. In this case, the presence of hypercalcemia was an important clue — a finding that was in clear contrast to the reduction in total serum calcium levels expected in pregnancy.

The morbidity associated with primary hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy is substantial, with complications reported in up to 67% of affected mothers and 80% of fetuses and neonates, usually in the presence of severe hypercalcemia10 (an increase in calcium levels of approximately 2 mg per deciliter [0.5 mmol per liter] or more above the normal range for pregnancy). Fetal complications associated with maternal hyperparathyroidism include restriction of intrauterine growth, low birth weight, preterm delivery, stillbirth, miscarriage, and neonatal tetany. The maternal complications are similar to those seen outside of pregnancy, including nephrolithiasis, pancreatitis, bone disease, changes in mental status, and hypercalcemic crisis. Pancreatitis during pregnancy is rare, occurring in 0.03% of pregnancies.8 Whereas some reports — most of them based on case series — have suggested an association between primary hyperparathyroidism and pancreatitis,11,12 a community-based study showed no increase in the incidence of pancreatitis among patients with primary hyperparathyroidism as compared with matched controls.13

An understanding of the normal pregnancy-induced alterations in levels of calcium and vitamin D (Table 1) is important in the assessment of a patient with hypercalcemia in pregnancy. During pregnancy, calcium is shunted from the maternal circulation to the fetus, in order to mineralize the developing fetal skeleton. The fetal calcium demand increases primarily in the third trimester, but the maternal adaptations to meet this demand start early in pregnancy. Maternal shunting of calcium to the fetus may contribute to relative maternal hypocalcemia, but the reduction in total maternal serum calcium levels observed in pregnancy is mainly a reflection of a decrease in serum albumin levels and, consequently, a decrease in the albumin-bound fraction of calcium1; ionized calcium levels remain in the normal range during pregnancy. 3,4 Longitudinal measurements of intact PTH levels have revealed decreases to the low-to-normal range during early pregnancy, with a subsequent increase to the midnormal range by term.3-5

A major maternal adaptation to the increased fetal calcium demand is increased intestinal absorption of calcium, mediated by an increase in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels. Maternal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels increase early in pregnancy and remain about twice as high as prepregnancy levels throughout pregnancy.4-7 The increase is attributed to PTH-independent up-regulation of 1α-hydroxylase in the maternal kidneys, with the placenta, decidua, and fetal kidneys possibly contributing additional amounts.5 The glomerular filtration rate also increases during pregnancy, as does urinary calcium excretion; the increased calcium excretion is probably a response to the increased intestinal absorption of calcium.7 Urinary calcium levels are commonly two to three times as high as they are in nonpregnant women4,7 and may be in a range that would be frankly hypercalciuric for nonpregnant women.7 Levels of other hormones related to calcium homeostasis that are affected by pregnancy are shown in Table 1. PTH-related protein stimulates placental calcium transport in the fetus14 and may also have a role in protecting the maternal skeleton.5,15 Calcitonin may play a role in protecting the maternal skeleton from increased resorption.5

The approach to the management of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy varies, depending on the presence or absence of symptoms and their severity; the gestational age; and the patient's preference. Conservative management with watchful waiting is often most reasonable for patients with mild, asymptomatic hypercalcemia (i.e., calcium levels that are slightly about the normal range for pregnancy). Increased oral intake of salt and fluids is recommended to prevent volume depletion. In more severe cases, intravenous hydration with isotonic saline is warranted; furosemide promotes urinary calcium excretion and may help in the treatment of patients with initial hypercalcemia, but it should be used only after volume repletion. Calcitonin, which is classified by the Food and Drug Administration as a category C medication for pregnant patients (i.e., a medication for which animal studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus, but no adequate, well-controlled studies have been conducted in humans; potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks), may bring about rapid reductions in calcium levels when administered intravenously or intramuscularly, but it is not a viable option for prolonged treatment, since tachyphylaxis rapidly develops. Bisphosphonates cross the placenta and are contraindicated in pregnancy owing to concern about their interference with fetal bone development.

Parathyroidectomy is the only definitive therapy and is generally recommended for cases of symptomatic and severe hypercalcemia. The second trimester is generally preferred for surgery, but for patients in whom medical management is ineffective, surgical intervention may be necessary irrespective of the stage of gestation. In all cases of maternal hyperparathyroidism, neonates should be followed closely for evidence of hypocalcemia resulting from suppression of PTH production by the neonatal parathyroid gland, which may not appear until several hours after delivery.

This case underscores the need to consider a broad differential diagnosis for problems in pregnancy and to interpret laboratory tests in the context of the complex metabolic alterations associated with pregnancy. In this patient, back and abdominal pain proved to be attributable to pancreatitis, which was probably caused by hypercalcemia associated with hyperparathyroidism. The detection of hypercalcemia and an inappropriately “normal” intact PTH level led to the identification of primary hyperparathyroidism, and surgical intervention in the second trimester resulted in a good outcome for both mother and infant.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢