This Journal feature begins with a case vignette highlighting a common clinical problem. Evidence supporting various strategies is then presented, followed by a review of formal guidelines, when they exist. The article ends with the author's clinical recommendations.

A 36-year-old woman has recurrent boils under both arms and in the groin. They flare premenstrually, causing pain, suppuration, and an offensive odor. Scarring has developed in the groin area, and chronically draining sinus tracts are interspersed with normal skin. Treatment with short courses of antibiotics or with incision and drainage has had no apparent effect, and she has become socially isolated because of embarrassment about her condition. How would you manage this case?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Hidradenitis suppurativa1,2 is a chronic, recurrent inflammatory disease affecting skin that bears apocrine glands. It usually develops after puberty, manifested as painful, deep-seated, inflamed lesions, including nodules, sinus tracts, and abscesses. In most patients, flares are accompanied by increased pain and suppuration at varying intervals, often occurring premenstrually in women. If untreated, the flares subside within 7 to 10 days.3

European studies have suggested that hidradenitis suppurativa is not a rare disease. A French community-based study,4 in which persons older than 15 years of age responded to a validated questionnaire (with a positive predictive value of 85 to 89%), showed a point prevalence at 1 year of 1%. Studies of young adults (18 to 33 years of age) undergoing screening for sexually transmitted diseases have shown point prevalences of up to 4%.5

Women are more frequently affected than men (female:male ratio, 3:1) and appear to be more likely to have genitofemoral lesions. The condition most commonly develops in persons in their early 20s, although the onset has been described in prepubertal children and in postmenopausal women as well.4,6, The prevalence of the disease appears to decline at an age of more than 50 years. 4

About one third of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa report a family history of the disease, and affected families with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance have been identified. In a small number of cases in which hidradenitis suppurativa is accompanied by severe acne and perifolliculitis capitis, the disease has been linked to chromosome 1p21.1–1q25.3 and mutations of the γ-secretase complex.7 Studies have not shown associations between HLA antigens and hidradenitis suppurativa.8

Cigarette smoking is a recognized risk factor for both the development of hidradenitis suppurativa and severe disease.9 Obesity is also a risk factor; the majority of patients are overweight, and both body-mass index and tobacco smoking have been directly correlated with the severity of this condition. 10

The disease has a substantial negative effect on the quality of life of affected persons, as compared with the general population or with patients who have other chronic skin conditions (e.g., psoriasis or eczematous dermatitis).11-13 Rates of sick leave from work are higher and self-reported general health is lower among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa than in the general population.14

Conditions reported to be associated with hidradenitis suppurativa include severe acne, acne conglobata, and pilonidal cysts, although it is possible that these conditions are misdiagnosed in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.1 Data from an epidemiologic study suggested a 50% increase in the risk of cancer of any kind in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, as compared with the general population15; specific cancers reported to occur more frequently in these patients included squamous-cell carcinoma (e.g., Marjolin's ulcers associated with chronic lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa, primarily of the buttocks), buccal cancer, and hepatocellular cancer. However, this study did not adjust for status with respect to cigarette smoking, and it is likely that the observed associations were confounded by smoking — a recognized risk factor for both hidradenitis suppurativa and these diseases.

The frequency of hidradenitis suppurativa has been reported to be increased among patients with Crohn's disease, affecting 17% of such patients, according to one report. A relationship between the two conditions is supported by clinical, histologic, and epidemiologic similarities, such as sinus tracts, granulomatous inflammation, scarring, and onset after puberty.16 Arthritis (rheumatoid factor–negative and HLA-B27–negative) is also more frequent among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa than in the general population and usually involves the peripheral joints, often in an asymmetric manner. 1

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa remains unclear. Histologic studies suggest that it is a multifocal disease, in which atrophy of the sebaceous glands is followed by an early lymphocytic inflammation and hyperkeratosis of the pilosebaceous unit and, later, by hair-follicle destruction and granuloma formation.17-22 It is speculated that subsequent healing processes (not well defined) produce scarring and sinus tract formation — processes that are exacerbated by the impaired mechanical integrity of the sinus tract epithelium.22 Recent investigations suggest that the interleukin-12–interleukin-23 pathway and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) are involved in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa, supporting the proposition that it is an immune or inflammatory disorder.23,24

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

Evaluation

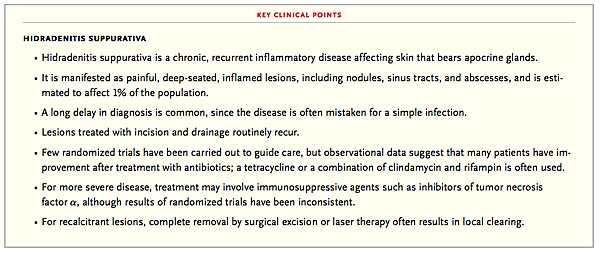

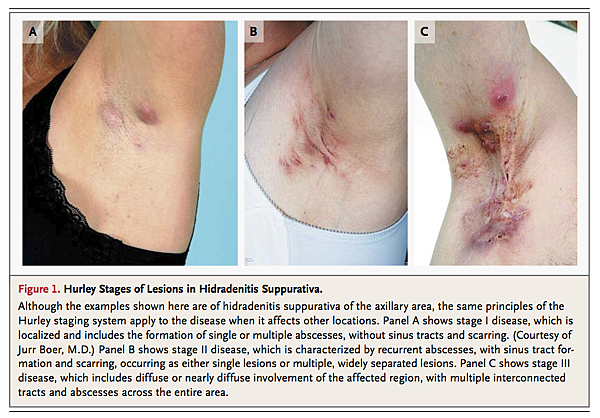

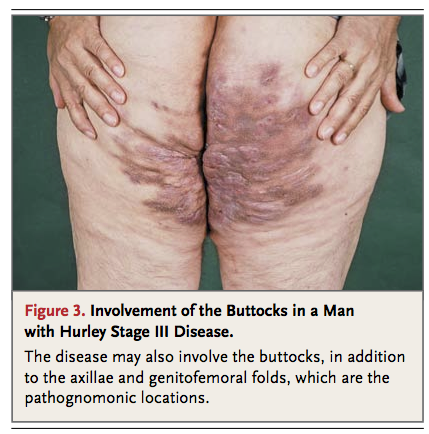

The diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa is generally made clinically. On physical examination, one may see characteristic inflamed and noninflamed nodules; draining and nondraining sinus tracts; and abscesses in the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. The lesions occasionally extend beyond these areas and appear around the anus, on the buttock, or on the breast in females. The nodules are located in the deeper dermis and are rounded rather than having the pointed, purulent appearance of simple boils (Figure 1FIGURE 1

Hurley Stages of Lesions in Hidradenitis Suppurativa., Figure 2FIGURE 2

Involvement of the Genitalia in a Woman with Hurley Stage III Disease.

, and Figure 3FIGURE 3

Involvement of the Buttocks in a Man with Hurley Stage III Disease.).

Secondary lesions such as pyogenic granulomas in sinus tract openings, plaquelike induration, ropelike scars, and giant multiheaded comedones may also be found.

In selected cases, additional testing may be helpful. Biopsies and bacterial cultures are indicated only in atypical or refractory cases. Routine bacteriologic studies of the lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa are most frequently negative, although flares may be associated with superinfection involving a range of bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus.25,26 If extensive surgery is planned, ultrasonography may help in the preoperative assessment by identifying subclinical extension of the lesions.27

Despite the typical presentation, the disease is often diagnosed only after a considerable delay; in one study, the median delay was 12 years.28 Many cases are misdiagnosed as common boils and treated with lancing or short-term antibiotic therapy — approaches that may seem effective at first (since flares tend to subside spontaneously after a week) but ultimately fail.

Assessment of the severity of the disease is helpful in guiding treatment and is generally based on the Hurley staging system (Figure 1).29 In the majority of cases, patients have stage II disease at the time of diagnosis, presumably reflecting diagnostic delay. Only about 1% of patients have progression to stage III disease.

Medical Management and Lifestyle Measures

Stage I (localized) disease is usually managed with topical therapy, whereas systemic therapy is recommended for more widespread or severe disease. Since data from randomized trials are limited, choices among treatments are generally guided by the results in case series and by clinical experience.

In a small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving patients who appeared by description to have mild disease (although no formal staging was performed), topical administration of clindamycin (10 mg per milliliter twice daily) was found to reduce the number of abscesses, nodules, and pustules at monthly evaluations during a 3-month course of treatment.30 Clinical experience has also supported the use of intralesional injections of glucocorticoids (e.g., triamcinolone, 2 to 5 mg) for individual lesions,1 although this therapy has not been well studied.

When topical treatment is insufficient, oral antibiotics (often those with antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory properties31) are commonly used. This approach is likewise based largely on clinical experience; one small, randomized trial in which oral tetracycline at a dose of 500 mg twice a day was compared with topical clindamycin given twice a day, each for 3 months, failed to show superiority of the oral therapy.32 Alternatively, combination antibiotic therapy is used, although data from randomized trials comparing this approach with single-agent oral therapy or topical therapy are lacking. In two case series involving a total of 190 patients with mild-to-severe disease who were treated with both clindamycin and rifampin (each typically given at a dose of 300 mg twice daily), scores for disease severity were reduced by 50%, as compared with baseline, and quality of life improved significantly.33,34, The results appeared to be similar for patients who received lower doses, and the authors speculated that the antiinflammatory effects of these drugs or natural variations in severity may play a role. However, these studies lacked controls and blinding; randomized trials are needed to confirm efficacy (including combined therapy vs. single-agent therapy) and to guide decisions about dosing and the duration of therapy.

In women with hidradenitis suppurativa, antiandrogens are sometimes used, although, as with other treatments, this treatment is based largely on anecdotal evidence.35,36 A 1-year, double-blind, crossover trial (with crossover after 6 months of treatment) involving 24 premenopausal women compared two regimens: ethinyl estradiol given from days 5 through 25 of the menstrual cycle plus cyproterone acetate given on days 5 through 14 versus the combination of ethinyl estradiol and cyproterone acetate given on cycle days 5 through 25. The benefits were found to be similar with the two regimens, as assessed by reductions in the frequencies of lumps and boils, the quantity of discharge, and the degree of pain and discomfort; overall, in 12 of the women (50%), the disease improved or cleared completely with either regimen.36

Case series have suggested a lack of benefit from isotretinoin.37,38 For example, among 48 patients treated with isotretinoin (mean dose, 0.6 mg per kilogram of body weight) for at least 4 months, fewer than one fourth had clearing of lesions, and most of the patients who had a response to the treatment had mild disease.37

In severe cases of hidradenitis suppurativa, systemic immunosuppressive agents have been used. Case reports have described rapid control of the disease in patients treated with cyclosporine (3 to 6 mg per kilogram).39,40 More recently, TNF-α inhibitors have been studied in randomized trials, with inconsistent results. In a randomized, double-blind, 8-week trial, infliximab (5 mg per kilogram) given at weeks 0, 2, and 6, as compared with placebo, resulted in a significant reduction in a composite score reflecting the extent of disease and ratings of drainage and pain. However, another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial failed to show a significant benefit of etanercept (50 mg twice weekly) with the use of a physician's global assessment scale.41,42 In a third randomized, controlled trial, adalimumab (40 mg given every other week after a loading dose of 80 mg) resulted in significant improvement on the basis of a score that reflected the extent and severity of disease at 6 weeks, but this benefit was not maintained at 12 weeks (the primary outcome of the trial).43

Since smoking and obesity are associated with severe hidradenitis suppurativa,10 affected patients should refrain from tobacco use and control their weight, although data are not available from randomized trials assessing the effects of such restrictions. Case reports describe the development or exacerbation of lesions as a result of mechanical stress, so rubbing of the affected skin should also be avoided.1

Surgical Management

In cases of individual scarred lesions or stage III disease, clinical experience suggests that surgical options offer the best chances for cure. For milder disease, topical or systemic therapy should be tried first because of the multifocal nature of the disease, with surgery reserved for unresponsive lesions. Scarring is not amenable to medical treatment, so the presence of considerable scarring should be considered a relative indication for surgery. Incision with drainage is discouraged, since recurrence is the norm.44 Furthermore, inflamed, nonfluctuating nodules do not drain readily.

Surgery can be either limited or extensive. Limited surgical interventions include exteriorization of sinus tracts (i.e., surgical removal of the “roof” of an abscess, cyst, or sinus tract, with the “floor” left intact for more rapid healing) and localized excision.45 Observational data indicate a substantially lower risk of recurrence among patients who undergo more extensive excision of all hair-bearing skin in the affected region (e.g., the axilla) than among those who undergo excision of inflamed lesions only46; this outcome was attributed to incomplete removal of diseased tissue when the latter procedure is used.

Laser and Radiation Therapy

Laser therapy has recently been adopted for use in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. In one randomized, controlled trial, monthly treatment with a neodymium:yttrium–aluminum–garnet laser for 3 months in patients with stage II or stage III disease resulted in a significant reduction in disease severity at follow-up a month after therapy was completed (based on a 65% reduction according to a validated disease-severity scoring system), as compared with a reduction of about 7% with topical antibiotic therapy (benzoyl peroxide 10% or clindamycin 1%).47 Although data from trials comparing surgical techniques with laser therapy are lacking, the use of healing by secondary intention (i.e., leaving the wound open to heal under a dressing) is widely advocated. In a case series of 24 lesions treated with a carbon dioxide laser and left to heal by secondary intention, the authors reported only two recurrences after a mean follow-up of 27 months.48 Likewise, another case series showed a low rate of local recurrence for lesions treated with a carbon dioxide laser, whereas flares in other, untreated regions were common during follow-up.49

The use of external-beam radiation therapy has also been described. In a review of 231 cases treated with a total dose of 3 to 8 Gy (175-kV orthovoltage therapy unit, with a 0.5-mm copper filter), active lesions resolved in about one third of the patients treated. However, this approach is rarely used because of concern that the long-term risks may outweigh its benefits.50

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

There is a paucity of data from randomized, controlled trials to guide decisions about therapy in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Controlled trials are needed to compare the effects of different regimens and durations of antibiotic therapy, to assess the efficacy of combination therapy as compared with monotherapy, and to compare antibiotic treatment with immunosuppressive treatment in severe cases. Similarly, there is a need for a systematic comparison of surgical techniques (e.g., laser vs. conventional surgery) and approaches to postprocedure management (open healing vs. primary closure or skin grafting).

GUIDELINES

No formal guidelines are currently available for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The patient described in the vignette presented with a history of recurrent lesions that are consistent with stage II hidradenitis suppurativa. Management should be guided by disease severity. For stage I, characterized by mild, nonscarring disease, limited clinical trial data support the efficacy of topical clindamycin; although data are lacking to support the use of intralesional triamcinolone, clinical experience suggests that it may be useful for some isolated lesions. Case series suggest that scarred lesions are best treated with wide excision or evaporation with the use of a carbon dioxide laser. More extensive and severe disease requires systemic treatment. For stage II disease, as seen in the patient described in the vignette, I would try combination antibiotic therapy (clindamycin and rifampin, 300 mg twice daily for 6 months), since it has appeared to be effective in case series and clinical practice, although the combined regimen has not been compared with either of these agents alone or with other treatments in randomized clinical trials.

Dr. Jemec reports receiving consulting fees from Abbott Laboratories, Merck, Pfizer, and Dumex-Alpharma, lecture fees from Galderma and Pfizer, and grant support from Abbott Laboratories, Photocure, and LEO Pharma; receiving equipment on loan from Michelson Diagnostics; and receiving reimbursement for travel expenses from Abbott Laboratories, Galderma, and Photocure.

Disclosure forms provided by the author are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

SOURCE INFORMATION

From the Department of Dermatology, Roskilde Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark; and Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Jemec at the Department of Dermatology, Roskilde Hospital, Roskilde DK-4000, Denmark, or at gbj@regionsjaelland.dk.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢