US Pharm. 2013;38(9):43-46.

ABSTRACT: More than 80% of pregnant women take OTC or prescription drugs during pregnancy, with only 60% of these patients consulting a health care professional when selecting a product. Common pregnancy-associated conditions include cough, cold, allergies, gastrointestinal disorders, and pain. The cough, cold, and allergy products most widely used during pregnancy are antihistamines, decongestants, antitussives, and expectorants. Current updates to the immunization schedule include administering tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine with each pregnancy. Influenza vaccination should also be recommended for all pregnant women and can be given in any trimester. The decision to treat pregnancy-associated conditions should be based on a number of factors, including safety, symptom severity, and potential for quality-of-life improvement.

The prevalence of medication use during pregnancy is widespread and on the rise. More than 80% of pregnant women take OTC or prescription drugs during pregnancy, with only 60% of these patients consulting a health care professional when selecting a product.1 There is a delicate risk-benefit estimation concerning the health of both the mother and the fetus that must be considered in the use of drugs during pregnancy.

A study investigating the use of prescription, OTC, and herbal medicines in a rural obstetric population of 578 participants found that over 90% of the patients took either prescription and/or OTC medication.2 A larger cohort study (multicenter, urban) found that 64% of expectant mothers had been prescribed a drug other than a vitamin or mineral supplement at some point during their pregnancy.3

Medication use during pregnancy can generally be attributed to preexisting conditions such as hypertension or cardiac problems, pregnancy-associated conditions such as nausea and vomiting, or acute conditions such as seasonal allergies or bacterial infections. Among the most frequently used medications in pregnancy are antiemetics, antacids, antihistamines, analgesics, antimicrobials, diuretics, hypnotics, and tranquilizers.4

Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks?

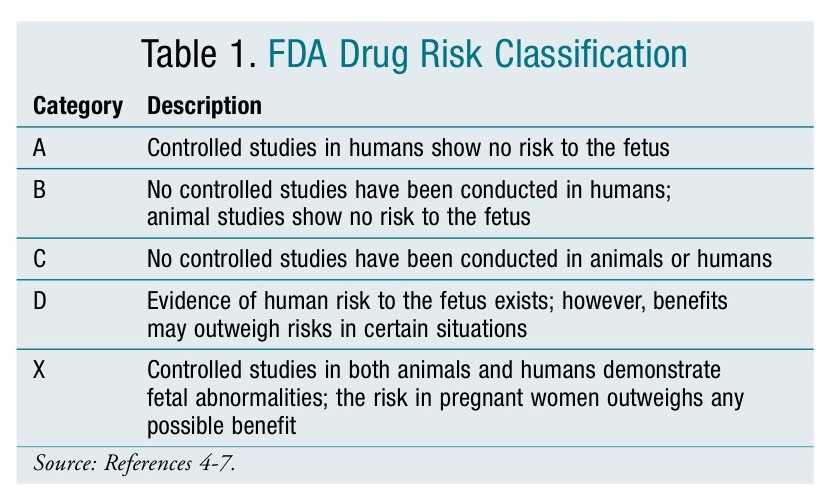

Drug use during pregnancy continues to remain a major concern due to the unknown effects on mother and fetus. Physicians are faced with difficult situations as they have very little information to help them decide whether the potential benefits to the mother outweigh the risks to the unborn fetus. To help guide physicians in their selection and interpretation of the risks associated with the drug, the FDA introduced a drug classification system in 1979 (TABLE 1).4-7 Most information provided in this classification is derived from animal studies and uncontrolled studies in humans such as postmarketing surveillance reports. To date, very few well-controlled studies have been conducted in pregnant women, most likely due to ethical considerations. Two important limitations of the classification include5-7:

- All new FDA-approved medications are classified as Category C

- There are no FDA regulations requiring further studies or seeking more data; therefore, changes in the classification are rare. In addition, the classification is often not changed when new data become available.

Approximately 20 to 30 of the most commonly used drugs are identified as teratogens, with 7% of the more than 1,000 medications listed in the Physicians’ Desk Reference classified as Category X.7 Some of the commonly used drugs with proven teratogenic effects in humans are warfarin, isotretinoin, valproic acid, and tetracycline antibiotics. The timing of fetal exposure to a drug is critical to the likelihood of an adverse effect occurring. Most of the major body structures are formed during the first trimester, and exposure during this time could lead to structural teratogenic effects.8 Some drugs have different FDA categorizations based on the trimester of pregnancy.

As pharmacists, we play a vital role in educating and counseling pregnant women on the risks associated with a drug. Informing a pregnant woman of the risks and possible fetal defects can reduce the number of complications. Furthermore, it is our responsibility to ensure that other health care professionals are familiar with the current literature available on the safety of drugs administered during pregnancy. This article will present a concise discussion of common medications used to treat pregnancy-associated conditions, including cough, cold, and allergies; pain; and gastrointestinal (GI) disorders; as well as provide an update on the current immunization recommendations for pregnancy.

Cough, Cold, and Allergy

It is very common for women to experience cough, cold, or allergy symptoms during pregnancy. The use of multiple OTC medications to treat these symptoms increases from the first to the third trimester. According to one study, 92.6% of the obstetric population interviewed self-medicated with OTC medications.2 The common cold is typically caused by numerous viruses and, therefore, is usually self-limiting. Pregnant women should be advised to first try nonpharmacologic treatments such as a saline nasal spray, the use of a humidifier, and increased hydration.9,10 The most commonly used cough, cold, and allergy products include antihistamines, decongestants, antitussives, and expectorants (TABLE 2).1

It appears that the older sedating antihistamines, also known as first-generation agents, are safe in pregnancy. The recommended first-line agent is chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton), which is Category B. According to the Collaborative Perinatal Project, chlorpheniramine use during pregnancy was not associated with an increased risk of malformations.7 Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) is also an option in patients who need symptomatic relief from allergy or cold symptoms. It is also Category B and was not associated with an increased risk of malformations; however, it can cross the placenta and has been reported to have possible oxytocin-like effects at high doses when used during labor.9

The newer nonsedating or second-generation antihistamines, such as loratadine (Claritin), fexofenadine (Allegra), and cetirizine (Zyrtec), have not been extensively studied. Cetirizine may be alternative to chlorpheniramine in the second or third trimester if a first-generation antihistamine is not tolerated.9,10

Administration of both inhaled and oral decongestants occurs during pregnancy. Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) and phenylephrine (Sudafed PE) are the most common oral OTC decongestants used, with 25% of pregnant women using pseudoephedrine as their oral decongestant of choice.11 However, its use should be avoided during the first trimester due to associated risk of defects from vascular disruption known as gastroschisis. Inhaled decongestants such as oxymetazoline (Afrin) and phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) are both Category C and appear to be safe for use.

The primary cough remedy used during pregnancy is dextromethorphan (Delsym). Many studies suggest that there is no association between dextromethorphan use and an increased risk of birth defects.9,10 However, many of the OTC products containing dextromethorphan also contain alcohol and should be avoided during pregnancy.

Guaifenesin (Mucinex) is the expectorant typically found in most OTC cold medications. Its use appears to be safe during pregnancy, with the exception of the first trimester.9

Pain

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used OTC analgesic in pregnancy, with at least 65.5% of women taking it at some point during pregnancy and 54.2% taking it during the first trimester.12 The use of single-ingredient acetamino-phen products during pregnancy has not been associated with increased risk of a broad range of birth defects.13-15 Due to its antipyretic effects, single-ingredient acetaminophen products have been associated with a decreased risk of some birth defects arising from febrile infection during pregnancy.14

Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided if possible during pregnancy. A recent study found that although the use of NSAIDs in early pregnancy does not appear to be a major risk factor for birth defects, there were a few moderate associations between NSAIDs and specific birth defects.16 Another major concern is the increased risk of miscarriage that has been associated with the use of nonaspirin NSAIDs during pregnancy.17 The use of NSAIDs during pregnancy is also associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus, fetal renal toxicity, and inhibition of labor.4,15,18 Although there are limited reproductive studies involving the use of narcotic analgesics in human pregnancies, these drugs have been used in therapeutic doses for many years by pregnant women without a link to an elevated risk of birth defects.15,19 The use of opioids should be reserved for pain that is not managed with acetaminophen and, when possible, the lowest effective dose should be used.15

GI Issues

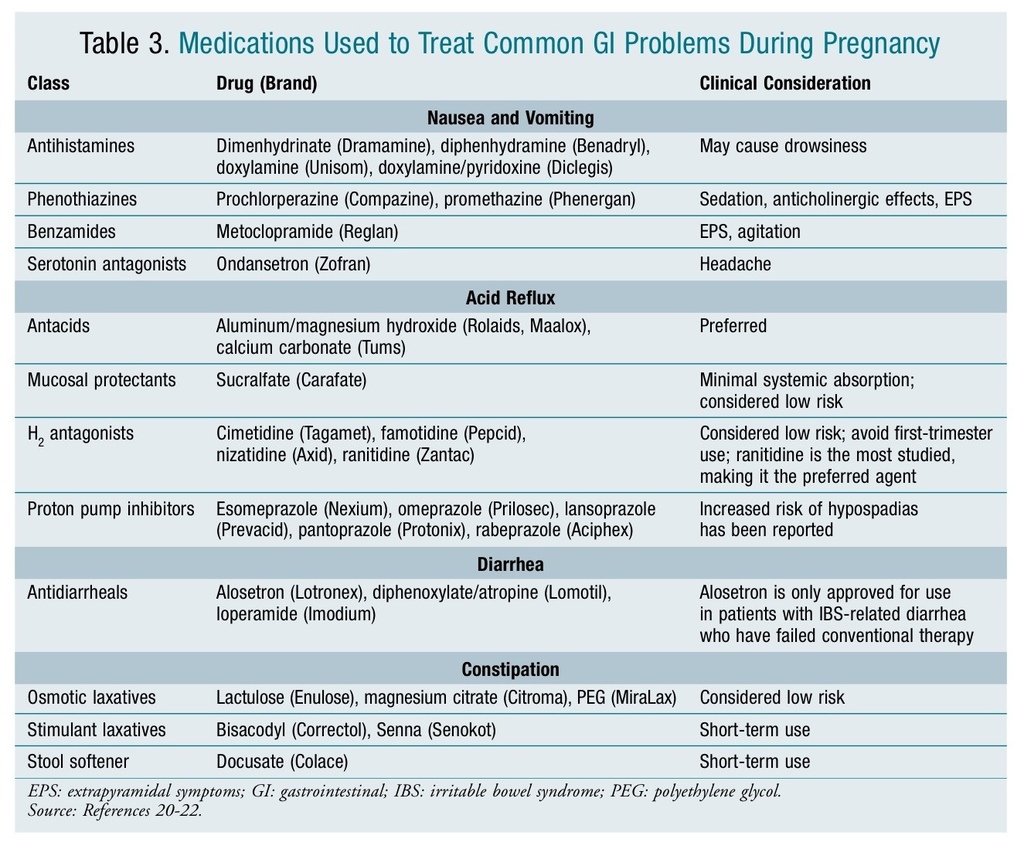

The most common GI problems that occur during pregnancy include nausea, vomiting, acid reflux, diarrhea, and constipation. Drug therapy may be required when lifestyle modifications cannot provide adequate relief of symptoms.

While nausea and vomiting are common indicators of early pregnancy, an extreme manifestation of the condition is termed hyperemesis gravidarum. Severe hyperemesis gravidarum complications—including weight loss >5% of initial body weight, electrolyte imbalance, and dehydration— are the second most common reason for prenatal hospitalization.20 A variety of medications with different mechanisms of action that have been used to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy are listed in TABLE 3.20-22

Acid reflux is another common problem estimated to occur in 30% to 50% of all pregnancies.23 Due to the pressure on the uterus, acid reflux during pregnancy is less likely to respond to lifestyle modifications such as elevation of the head when sleeping, eating small frequent meals, or avoiding eating within 3 hours of bedtime.24 OTC antacids are considered the agents of first choice with the exception of magnesium trisilicate (Gaviscon) and sodium bicarbonate (Neut), which should be avoided during pregnancy. Long-term use of high-dose magnesium trisilicate has been associated with increased risk of fetal nephrolithiasis, hypotonia, and respiratory distress; sodium bicarbonate has been associated with metabolic acidosis and fluid overload.23 A variety of agents that have been used to treat acid reflex during pregnancy are listed in TABLE 3.20-22

Diarrhea and constipation are also frequent problems associated with pregnancy. TABLE 3 lists agents used to treat these conditions.20-22 Castor oil and mineral oil should be avoided for the treatment of constipation. Alosetron (Lotronex) is only indicated for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)–associated diarrhea. Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol, Kaopectate) should be avoided in pregnancy because the salicylate moiety can lead to increased perinatal mortality.21

Immunizations

Women who are considering pregnancy or those already pregnant should be advised on the importance of receiving vaccines. Informing these patients of the benefits of receiving certain vaccinations can significantly reduce the occurrence of preventable diseases. With the many vaccines available, and pharmacists at the front lines as immunizers, it is important to discuss the agents utilized for specific groups of patients. The following are a few of the current recommendations for vaccine use during pregnancy.

The most current update to the immunization schedule was the recommendation to administer tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine with each pregnancy during the 27th to 36th week of gestation. This is different from prior recommendations that were dependent upon previous vaccination history. Waiting until the second trimester is reasonable to minimize concerns about possible adverse reactions.25 Healy et al concluded that the infants of mothers immunized either before their pregnancy, or in early gestation, displayed insufficient antibodies to aid in infant protection from disease.26 Furthermore, the antibodies that were transferred were lost within a 6-week period, which could possibly place the infant at risk of infection.26

Influenza vaccination should be recommended for all pregnant women for prevention of seasonal influenza and can be administered in any trimester. It is most beneficial when given as early as available in the flu season.27 The immunizations contraindicated during pregnancy are live vaccinations, which include influenza (LAIV); measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); varicella; and zoster.25

Conclusion

Most women will take medications at some point during pregnancy. It is important to consider the risks and benefits of drug therapy to both mother and fetus. The decision to treat should be based on a number of factors, including the safety profile of the drugs in question, symptom severity, and potential for quality-of-life improvement.

REFERENCES

1. Black RA, Hill DA. Over-the-counter medications in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2517-2524.

2. Glover DD, Amonkar M, Rybeck BF, Tracy TS. Prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal medicine use in a rural, obstetric population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1039-1045.

3. Andrade SE, Gurwitz JH, Davis RL, et al. Prescription drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:398-407.

4. Gunatilake R, Patil AS. Drugs in pregnancy. Merck Manual Online for Health Care Professionals. January 2013. www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gynecology_and_obstetrics/drugs_in_pregnancy/drugs_in_pregnancy.html?qt=drugspregnancy&alt=sh. Accessed May 15, 2013.

5. Koren G, Pastuszak A, Ito S. Drugs in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1128-1137.

6. Invasive cancer incidence—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:113-118.

7. Hansen WF, Peacock AE, Yankowitz J. Safe prescribing practices in pregnancy and lactation. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47:409-421.

8. Rakusan K. Drugs in pregnancy: implications for a cardiologist. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2010;15:e100-e103.

9. Cough and cold medicine use in pregnancy. Pharm/Prescr Ltr. 2006;22:221112.

10. Erebara A, Bozzo P, Einarson A, Koren G. Treating the common cold during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:687-689.

11. Cabbage LA, Neal JL. Over-the-counter medications and pregnancy: an integrative review. Nurse Pract. 2011;36:22-28.

12. Werler MM, Mitchell AA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Honein MA. Use of over-the-counter medications during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:771-777.

13. Rebordosa C, Kogevinas M, Bech BH, et al. Use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:706-714.

14. Feldkamp ML, Meyer RE, Krikov S, Botto LD. Acetaminophen use in pregnancy and risk of birth defects: findings from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:109-115.

15. Analgesics in pregnancy and lactation. Pharm/Prescr Ltr. February 2012. PL Detail-Document #280211. http://twileshare.com/uploads/Analgesics.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2013.

16. Hernandez RK, Werler MM, Romitti P, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use among women and the risk of birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:228.e1-228.e8.

17. Nakhai-Pour HR, Broy P, Sheey O, Bérard A. Use of nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion. CMAJ. 2011;183:1713-1720.

18. Koren G, Florescu A, Costei AM, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during third trimester and the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:824-829.

19. Babb M, Koren G, Einarson A. Treating pain in pregnancy. Motherisk. 2010. www.motherisk.org/prof/updatesDetail.jsp?content_id=922. Accessed May 15, 2013.

20. King TL, Murphy PA. Evidence-based approaches to managing nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54:430-444.

21. Gastrointestinal drug use in pregnancy. Pharm/Prescr Ltr. 2006;22:221210.

22. Anderka M, Mitchell AA, Louik C, et al. Medications used to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:22-30.

23. Mahadevan U, Kane S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the use of gastrointestinal medications in pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:283-311.

24. Mahadevan U, Kane S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute medical position statement on the use of gastrointestinal medications in pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:278-282.

25. Guidelines for vaccinating pregnant women. Vaccines & immunizations. CDC. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/preg-guide.htm. Accessed May 22, 2013.

26. Healy CM, Rench MA, Baker CJ. Importance of timing of maternal combined tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization and protection of young infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:539-544.

27. AHFS Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc; 2013.

- See more at: http://www.uspharmacist.com/content/d/feature/c/43164/#sthash.hUgJxz9y.dpuf

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢