Nutrition Volume 26, Issue 9, September 2010, Pages 902-909

Objective

Lactoferrin, a whey milk protein after removing precipitated casein, has a prominent activity against inflammation in vitro and systemic effects on various inflammatory diseases have been suggested. The objective was to determine dietary effects of lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk on patients with acne vulgaris, an inflammatory skin condition.

Methods

Patients 18 to 30 y of age were randomly assigned to ingest fermented milk with 200 mg of lactoferrin daily (n = 18, lactoferrin group) or fermented milk only (n = 18, placebo group) in a 12-wk, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acne lesion counts and grade were assessed at monthly visits. The condition of the skin by hydration, sebum and pH, and skin surface lipids was assessed at baseline and 12 wk.

Results

Acne showed improvement in the lactoferrin group by significant decreases in inflammatory lesion count by 38.6%, total lesion count by 23.1%, and acne grade by 20.3% compared with the placebo group at 12 wk. Furthermore, sebum content in the lactoferrin group was decreased by 31.1% compared with the placebo group. The amount of total skin surface lipids decreased in both groups. However, of the major lipids, amounts of triacylglycerols and free fatty acids decreased in the lactoferrin group, whereas the amount of free fatty acids decreased only in the placebo group. The decreased amount of triacylglycerols in the lactoferrin group was significantly correlated with decreases in serum content, acne lesion counts, and acne grade. No alterations in skin hydration or pH were noted in either group.

Conclusion

Lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk ameliorates acne vulgaris with a selective decrease of triacylglycerols in skin surface lipids.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a widely prevalent skin condition that affects nearly 80% of adolescents and most of the population at some point in their lives [1], [2]. The earliest non-inflammatory acne lesions may be no more than a minor annoyance, but in persons with more harsh inflammatory acne lesions, embarrassment, social withdrawal, and physical and psychological scarring can be life-changing [3], [4].

The earliest non-inflammatory lesions in acne vulgaris are microcomedones, which are formed as a result of follicular plugging and sebaceous gland hyperplasia with increased sebum production [1], [5], [6]. As the lesions increase in size, they become non-inflamed closed or open comedones (whiteheads or blackheads, respectively) [1], [5], [6]. In time the comedones may fill with Propionibacterium acnes bacteria, which secrete chemotactic and proinflammatory byproducts, inflammatory cellssurround the follicle, disperse through the follicular wall, and lead to larger and inflammatory lesions, such as papules, pustules, and nodular cystic lesions [1], [5], [6].

A better understanding of the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris, coupled with an adverse effect and the lack of therapeutic benefit of pharmaceutical agents, is developing new insights into the relation among food intake, dietary supplements, and skin health [7]. Low–glycemic-load diets have been reported to improve symptoms of acne vulgaris in adolescent patients [8]. Experimental evidence has suggested that increased ingestion of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid can decrease inflammatory acne lesions by inhibiting the synthesis of proinflammatory eicosanoids [9]. In addition, daily ingestion of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and acidophilushas been shown to relieve acne symptoms by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines [10]. Lactoferrin has also been shown to decrease skin inflammation due to its broad antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities [11].

Lactoferrin is a whey milk protein after removing precipitated casein [12], [13]. Although it is not the major whey protein, lactoferrin is known to have prominent activities against inflammation and microbial infection in vitro [11], [12], [13]. As an iron-binding protein, it sequesters iron that is essential for microbial growth, and it can also bind directly to the bacterial membrane and increase bacterial membrane permeability for bacteriocidal activity [11], [12], [13]. It also modulates the immune system by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines [14], [15], [16]. However, most anti-inflammatory activities of lactoferrin have been observed in in vitro studies [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16] and little information is available on the systemic effects of lactoferrin as a dietary supplement. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the dietary effects of lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk on patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris, a prevalent inflammatory skin condition.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study protocol was approved by the Kyung Hee University/Kyung Hee Medical Center human investigation review committee (Seoul, Korea). Patients signed informed-consent forms before inclusion. Clinical investigations were conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki principles. Healthy male and female patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris of the face, with at least 15 inflammatory and/or non-inflammatory lesions but no more than three nodulocystic lesions and an acne grade of ≥2.0 to <4.0 [17] were included in the study. Individuals were excluded if they were currently receiving acne treatment of any kind including natural or artificial ultraviolet therapy or did so at any stage of their participation in this study. Other exclusion criteria included those conditions that could interfere with the efficacy evaluation of treatment (such as facial skin disease, acute disease, or chronic disease).

Clinical study design

In a 12-wk, open, double-blind, randomized clinical study, 56 patients (n = 28, 11 men and 17 women, per group; mean age 21.8 ± 0.3 y, range 18–30 y) received 200 mg of lactoferrin mixed in fermented milk containing probiotics (L. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus; lactoferrin group) or the control product (fermented milkcontaining probiotics only; placebo group) daily. Subjects were provided with bottles of fermented milk on a weekly basis. During the study period, compliance was monitored weekly by regular telephone interviews. Subjects were requested to refrain from consuming fermented milk products starting 2 wk before the beginning of the study and until the study had finished. To avoid the influence of other factors on clinical improvement of acne and skin condition, subjects were also requested not to change their cleaning habits and their usual moisturizing products throughout the study. However, to avoid disturbance of the probe in the corneum meter, sebum meter, and skin-pH meter, moisturization of the evaluated body areas was forbidden on the day of dermatologic assessment. All adverse events were recorded throughout the study. Blood samples for hematology and biochemistry and routine urine analysis with a pregnancy test (women only) were performed at 0 wk (baseline) and 12 wk. Thirteen subjects dropped out for personal reasons (six men and one women in the lactoferrin group and one man and five women in the placebo group). Seven subjects' data were excluded from evaluation due to non-compliance (two men and one woman in the lactoferrin group and four women in the placebo group). Thus, data from 36 subjects were entered for statistical evaluation (n = 18 in lactoferrin group, 3 men and 15 women, 22.7 ± 0.6 y old; n = 18 in placebo group, 10 men and 8 women, 22.2 ± 0.5 y old).

Clinical assessment

To evaluate treatment efficacy, clinical assessment of facial acne was performed by the same dermatology registrar who was blind to the group assignment of subjects. The dermatology registrar counted acne-related lesions (non-inflammatory lesions: open and closed comedones; inflammatory lesions: papules, pustules, and nodules) at monthly visits (0, 4, 8, and 12 wk) and evaluated acne severity according to the Leeds revised acne grading system at baseline and 12 wk [17]. To document efficacy, photographs of facial areas of subjects who gave written informed consent were taken under standardized conditions at baseline and 12 wk.

Measurement of skin condition

Under the standardized room conditions of 22°C to 24°C and 55% to 60% humidity, subjects were given at least 30 min to relax so that the skin condition could achieve equilibrium. Epidermal hydration of facial skin was measured with a corneum meter (CM825, Courage-Khazaka, Cologne, Germany) at baseline and 12 wk. Sebum content and pH of facial skin were measured using a sebum meter (SM815, Courage-Khazaka) and a skin-pH meter (PH905, Courage-Khazaka), respectively, at baseline and 12 wk. Skin hydration, sebum content, and pH values were the average of at least five determinations after equilibrium was attained. All data were stored electronically using a laptop computer and appropriate software (Courage-Khazaka). The temperature and humidity of the probe were also recorded.

Analysis of skin surface lipid

The skin surfaces of the forehead and cheek from subjects who gave written informed consent (n = 14, 3 men and 11 women, in the lactoferrin group; n = 14, 4 men and 10 women, in the placebo group) were stripped using 10 tape strips (14-mm D-SQUAME Tape; Cu-Derm Corporation, Dallas, TX, USA) at baseline and 12 wk. All tape strips from each subject were combined and stored at −20°C until required. Corneocytes were removed from the tapes by sonication in methanol and the lipids were extracted in Folch's solution (CHCl3:MeOH, 2:1, v/v) as reported previously [18]. The top phase was used to measure protein concentration by a modified Lowry method [19]. The extracted lipids (lower phase) were subjected to high-performance thin-layer chromatography on 0.20-mm silica gel 60-coated plates (Whatman, Clifton, NJ, USA) according to the modified method of Uchida et al. [20]. The fractions containing triacylglycerols (TGs), fatty acids, cholesterol, and ceramides that comigrated with respective standards were scanned at 420 nm with a TLC III scanner (CAMAG, Muttenz, Switzerland) and were quantified by calibration curves using various concentrations of external standards of each lipid.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were carried out on a per-protocol basis with SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences within each group were analyzed by paired t test for changes from baseline. To test differences between groups, unpaired Student's t test was used for normally distributed variables and Mann-Whitney U test for variables that were not normally distributed.

Univariate analysis was performed to determine the influence of gender on changes of acne lesion count and acne grade over 12 wk using a general linear model. In this analysis, acne lesion count and acne grade were used as dependent variables and gender (female coded 0, male coded 1) was used as an independent variable. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed to determine correlations of changes of skin surface lipids with changes of sebum content, acne lesion count, or acne grade over 12 wk. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical assessment

The baseline characteristics of the subjects are listed in Table 1. There were no differences between male and female subjects for any of the baseline characteristics; therefore, the data for male and female subjects were combined. There was no difference in body weight and body mass index between groups. The clinical severity of acne vulgaris at baseline matched well to dermatologic assessment as inflammatory lesion count (ILC), total lesion count (TLC), and acne grade, which were not significantly different between groups. Tolerability of the fermented milk was excellent in both groups. Changes of usual cleaning and moisturizing product and adverse events were not reported during the study period. Hematology, serum analysis, and urine analysis were normal and did not change in either group during the study period (data not shown).

Detailed data on acne lesion counts of individual subjects in the lactoferrin and placebo groups are presented in Table 2, Table 3. Compared with baseline, all 18 subjects demonstrated decreases in TLC with percent changes from −16.7 to −80.6, and 17 of these subjects (94.4%) had decreases in ILC with percent changes from −16.7 to −100.0 at 12 wk; one subject in the lactoferrin group reported no decrease in ILC (Table 2). The significant decreases in ILC and TLC were observed at all time points from 4 wk for all subjects (male and female combined) in the lactoferrin group. In the placebo group, 13 of 18 subjects demonstrated decreases in TLC with percent change from −11.1 to −66.3, and 12 subjects (66.7%) had decreases in ILC with percent changes from −25.0 to −100.0 at 12 wk; approximately five to six subjects reported no decrease or increases in ILC (0 ∼ +250%) and TLC (0 ∼ +50.0%) over 12 wk (Table 3). Although the significant decrease in TLC was observed at all time points from 4 wk, ILC was not significantly lower at 12 wk for all subjects (male and female combined) within the placebo group.

When the differences in changes over 12 wk were compared between groups, there was no statistically significant difference in changes of ILC, TLC, and acne grade of all subjects between the lactoferrin and placebo groups at 4 and 8 wk (data not shown). However, the ILC of all subjects was decreased by 38.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] −7.3 to 84.6, P = 0.019), and the TLC of all subjects was decreased by 23.1% (95% CI −1.3 to 47.5, P = 0.033) in the lactoferrin group compared with the placebo group at 12 wk (Table 4). In parallel, the acne grade of all subjects in the lactoferrin group also decreased by 20.3% (95% CI 2.6–38.0, P = 0.023) at 12wk. Despite a gender imbalance of subjects between the lactoferrin group (n = 18, 3 men and 15 women) and the placebo group (n = 18, 10 men and 8 women), gender was not the significant discriminating factor for the changes of acne lesion count and acne grade over 12 wk (lactoferrin group: P = 0.251 for ILC, P = 0.561 for TLC, P = 0.809 for acne grade; placebo group: P = 0.775 for ILC, P = 0.992 for TLC, P = 0.319 for acne grade) in each group, indicating that there was no gender effect on changes of ILC, TLC, and acne grade between the lactoferrin and placebo groups over 12 wk. Examples of decreased acne in the lactoferrin group are shown in Figure 1.

Measurement of skin condition

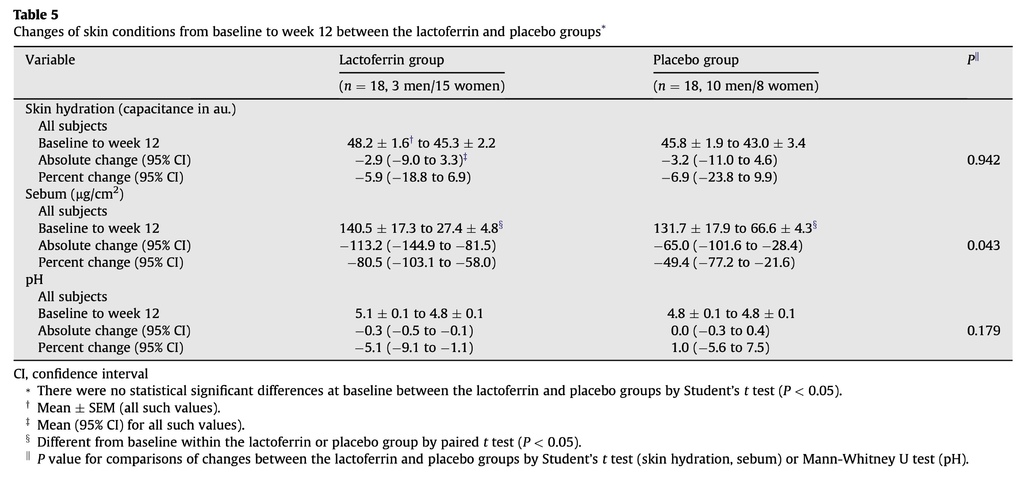

With no gender effect of acne lesion counts and acne grade, the data of male and female subjects for skin condition were combined as all subjects and are listed in Table 5. There were no differences in skin hydration, sebum, and pH between the lactoferrin and placebo groups at baseline. The skin hydration and pH of both groups remained unchanged during the study period, with no difference in change between the two groups. Notably, sebum content decreased in both groups; however, the decrease was more significant in the lactoferrin group at 12 wk (lactoferrin group, P < 0.0001; placebo group, P = 0.002), and thus sebum content in the lactoferrin group was decreased by 31.1% (95% CI −7.4 to 69.6, P = 0.043) compared with the placebo group.

Analysis of skin surface lipid

Analysis of skin surface lipid showed that the amounts of total lipids in both groups significantly decreased over 12 wk (lactoferrin group 17 307.8 ± 2296.2 μg/μg protein at baseline, 9306.3 ± 1773.6 μg/μg protein at 12 wk; placebo group 16 806.4 ± 2625.5 μg/μg protein at baseline, 10 596.3 ± 1995.9 μg/μg protein at 12 wk; Fig. 2), which was significantly correlated with decreases in sebum content (r = 0.474, P = 0.011) and TLC (r = 0.489, P = 0.008) over 12 wk after pooling data from both groups. Of the major skin surface lipids [21], amounts of TGs and free fatty acids (FFAs) decreased significantly in the lactoferrin group, whereas the amount of FFA decreased significantly only in the placebo group from baseline to 12 wk; the amount of TGs remained unchanged in the placebo group. Furthermore, the decreased amount of TGs in the lactoferrin group was significantly correlated with decreases in sebum content (r = 0.684, P = 0.007), ILC (r = 0.573, P = 0.032), TLC (r = 0.680, P = 0.007), and acne grade (r = 0.607, P = 0.021; Fig. 3), of which there was a stronger correlation with sebum content or TLC than with total lipids after pooling data from both groups. Amounts of cholesterol or ceramides in either group remained unchanged over 12 wk. These results indicate that although amounts of total lipids decreased in parallel with decreases in sebum content and TLC in both groups, the selective decrease in TG amount was a metabolic feature that led to a further decrease in sebum content and decreased acne in the lactoferrin group.

Discussion

New insights into the beneficial effects of food intake and dietary supplements on health improvement have developed [22], [23]. Specifically, human intervention studies with a low–glycemic-load diet, ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and Lactobacillus GG [8], [9], [10] have been reported to exert beneficial effects on skin health. In vitro studies [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16] and results from orally administered studies in animals [24] have provided evidence that lactoferrin has anti-inflammatory activity. In the present study we demonstrated for the first time that daily ingestion of lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk has a therapeutic effecton acne vulgaris, an inflammatory skin condition. Compared with baseline, acne grade, ILC, and TLC decreased significantly in the lactoferrin group at 12 wk. In contrast, acne grade and ILC did not change after 12 wk in subjects who consumed fermented milk only (placebo group).

The dermatologic improvement of acne vulgaris in the lactoferrin group was accompanied by a significant decrease in sebum content, which is overproduced in acne [25]. Decreased sebum excretion could be related to lower follicular colonization by P. acnes bacteria, which secrete chemotactic and proinflammatory byproducts [26], [27]. Decreased colonization by P. acnes leads to a decrease in inflammation, which has been observed clinically in acne [26], [27]. However, the sebum content and TLC were decreased in the placebo group, suggesting that the decreases in sebum content and TLC in the lactoferrin and placebo groups may at least in part be due to ingestion of fermented milk containing probiotics (L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus). Ingestion of probiotics has been reported to induce dermatologic improvement. For example, L. bulgaricus and acidophilus ameliorate acne symptoms [10]. Moreover, L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus enhance the protective immune response [28]. These findings, reports of fermented milk decreasing skin inflammation in a murine model of allergic contact dermatitis(Lactobacillus casei DN-114 0010) [29], and the effects of L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus on decreasing inflammation [30] suggest that after eating probiotics, systemic immunomodulation occurs, ultimately inducing beneficial effects on the decreases in sebum content and TLC in acne symptoms.

The greater improvement in acne in the lactoferrin group could be explained by the prominent effect of lactoferrin on decreasing the sebum content and inflammation. Lactoferrin may decrease lipid accumulation in the sebaceous glands or could have direct bacteriocidal activity resulting in lower sebum production and inflammation [12], [13], [31]. However, ingested lactoferrin or partially digested lactoferrin peptide fragments produced by pepsin proteolysis are not likely to be transported from the intestine into the circulatory system [32]. It seems more likely that ingested lactoferrin or lactoferrin peptide fragments indirectly promote systemic immune responses [33]. Orally administered lactoferrin can increase the number of cells in the lymph nodes and the spleen, enhance the activity of peritoneal macrophages and splenic natural killer cells, and enhance the production of cytokines such as interleukin-18, interleukin-12, and interferon-γ [34], [35], [36]. Circulation of cytokines and/or recruitment of immune cells may mediate the lactoferrin-induced decreases in sebum content and inflammation. However, the systemic effect of lactoferrin on acne vulgaris could be due to complex mechanisms; these remain to be elucidated in future studies.

Skin surface lipids extracted by the tape stripping method are of epidermal and sebaceous origin [37] and are composed mainly of TGs, FFAs, ceramides, cholesterol, and cholesterol esters [21], [38]. TGs originate from sebaceous glands, ceramides are of epidermal origin [38], and FFA is produced by the epidermis and sebaceous glands. TGs and FFAs were the major skin surface lipids in subjects with acne in both groups, consistent with previous studies [25], [38]. However, the relative ratio of epidermal lipids to sebaceous lipids depends on the body region: the skin regions of the forehead and cheek, from which skin surface lipids were collected in this study, have a high density of sebaceous glands [25], [38]; therefore, FFAs were more likely to be of sebaceous origin in subjects with acne in both groups. At 12 wk, the amount of FFAs decreased significantly in the placebo and lactoferrin groups; this was paralleled by decreases in sebum content and TLC, suggesting that the decreases in FFA and sebum are due in part to ingestion of fermented milk containing probiotics. An increase in cholesterol and its esters, another lipid class known to be produced by the epidermis and sebaceous glands, is also related to acne symptoms [39]. Furthermore, ceramides have been implicated in the impairment of water barrier function in skin with acne [25]. However, because these lipids are not major skin surface lipids and not altered significantly, we did not investigate these further in this study.

Dermatologic improvement of acne vulgaris was observed in the lactoferrin group only, with a selective decrease of TGs, the major sebum lipid [24], [37]. The greater efficacy of lactoferrin over probiotics may be associated with the greater ability of lactoferrin to decrease TGs and sebum content, thereby decreasing follicular plugging and inflammation with P. acnes bacteria. In support of this hypothesis, dietary supplementation with lactoferrin selectively lowered the amount of TGs excreted, and that of ILC. Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated that an increase of TG excretion over FFA is related to the incidence of acne vulgaris in the 20s [38], the same age range of subjects in this study.

Conclusions

This clinical study demonstrated a novel observation that daily ingestion of lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk decreases acne vulgaris with a selective decrease in TGs in skin surface lipids. Lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk may be a potential alternative therapy or may serve as an adjunct to conventional therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢