Abstract

Tattoos cause a broad range of clinical problems. Mild complaints, especially sensitivity to sun, are very common and seen in 1/5 of cases. Medical complications are dominated by allergy to tattoo pigment haptens or haptens generated in the skin, especially in red tattoos but also in blue and green tattoos. Symptoms are major and can be compared to cumbersome pruritic skin diseases. Tattoo allergies and local reactions show distinct clinical manifestations, with plaque-like, excessive hyperkeratotic, ulcero-necrotic, lymphopathic, neuro-sensory, and scar patterns. Reactions in black tattoos are papulo-nodular and non-allergic and associated with the agglomeration of nanoparticulate carbon black. Tattoo complications include effects on general health conditions and complications in the psycho-social sphere. Tattoo infections with bacteria, especially staphylococci, which may be resistant to multiple antibiotics, may be prominent and may progress into life-threatening sepsis. Contaminated tattoo ink is an open-window risk vector that can lead to epidemic tattoo infections across national borders due to contaminated bulk production. Hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transferred by tattooing remain a significant risk needing active prevention. It is noteworthy that cancer arising in tattoos, in regional lymph nodes, and in other organs due to tattoo pigments and ingredients has not been detected or noted as a significant clinical problem hitherto, despite millions of people being tattooed for decennia. Clinical observation and epidemiology disagree with register data, which indicate an increased risk of cancer due to chemical carcinogens present in some inks. Registers rely on chronic dosaging of cell lines and animals. However, tattooing in humans is essentially a single-dose exposure, which might explain the observed discrepancy.

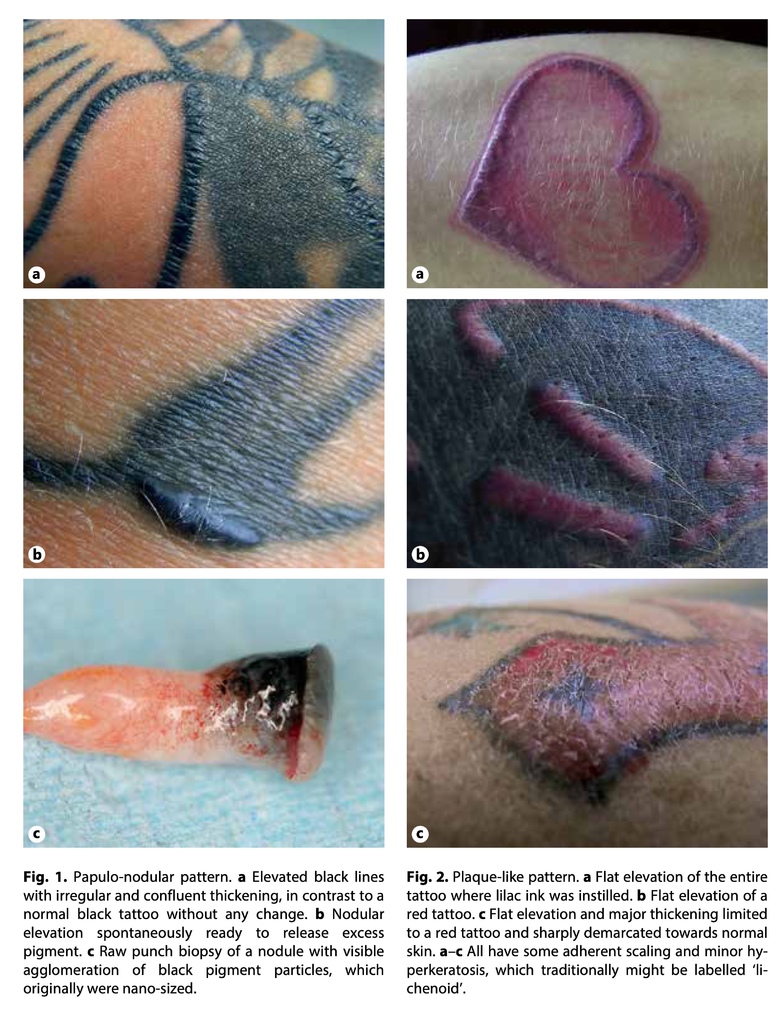

Plaque-Like Pattern (fig. 2)

These reactions show flat thickening and elevation of the entire tattoo at any site in the tattoo where the problem colour was inserted. Large adherent scales may or may not be present. Inflammation, with lymphocytes, is often major and may extend into the surrounding non-tattooed skin, and is concentrated in the outer dermis. Histology may show interface dermatitis or any of the traditional histologic patterns, which may overlap in the same biopsy. Epidermal changes with some degree of hyperkeratosis are typical. If the tattoo is a line, such as in tattooed texts, the entire line will be affected. Plaque-like reactions are primarily seen in red tattoos or in nuances of red and are a manifestation of allergy. Green and blue tattoos may also show this pattern as a result of allergy. There may be a visible colour shift from blue to green or from green to blue as the allergic reaction appears.

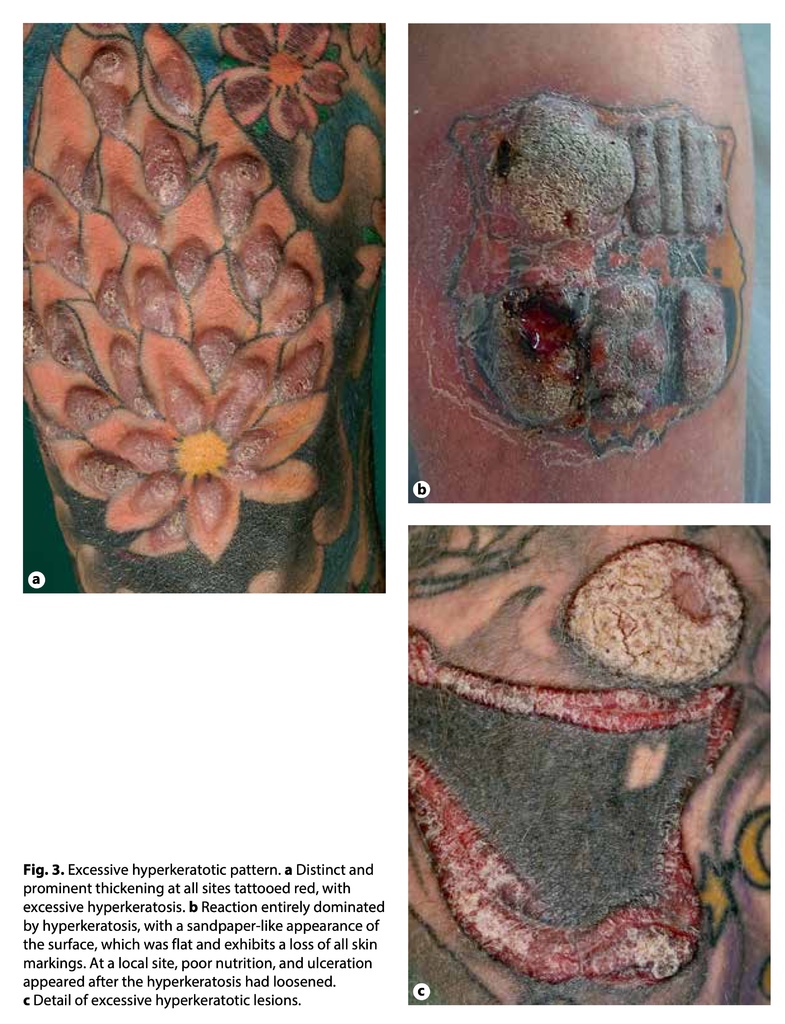

Excessive Hyperkeratotic Pattern (fig. 3)

These reactions exhibit inflammation, thickening, and elevation that is major and dominated by massive hyperkeratosis and cornification of the surface, which acquires a structure resembling sandpaper. The entire area dyed with the particular problem colour exhibits the same abnormality. The elevated surface is rather flat, and the pattern might be considered as a plaque-like reaction with an excessive epidermal response to the underlying inflammation. The thickened epidermis may become necrotic and ulcerate. Occasionally, epidermal folding and notches may appear on histology. The notches may go deep and result in epidermal inclusions and fistulas embedded deeply in the dermis. The histologic picture ultimately may be distinct, seen under the microscope as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The excessive hyperkeratotic pattern appears in red tattoos and nuances of red. The pattern is considered to indicate allergy, complicated by significant leakage of the basement membrane, escape of the culprit pigment to the epidermis, severe inflammation, and a prominent proliferative response of the epidermis that manifests as excessive hyperkeratosis. In raw punch biopsies, the hyperkeratosis is seen as a whitish layer on top of the underlying dermis, which is colourful due to the red pigment.

Ulcero-Necrotic Pattern (fig. 4)

Aggressive inflammation is directly followed by tissue necrosis and ulceration at any site in the tattoo where the culprit colour was instilled into the skin. Ulceration may affect the full thickness of the dermis and may approach the subcutaneous fat. Necrosis may even extend further into deep tissues if the culprit pigment is disseminated down to the underlying muscle fascia, for example. Necrosis may even affect the regional lymph nodes holding the same pigment. This pattern, especially seen in red tattoos, is a manifestation of a strong allergy. The allergy and haptenisation, seemingly involving tissue components, may progress to autoimmunity, with an attack on non-tattoo sites of the skin integument, including inflammatory reactions, vasculites, bullous reactions, and generally delayed wound healing throughout the skin. The condition may be self-limiting and may heal over a period of several months. Surgical excision is risky and relatively contraindicated.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢