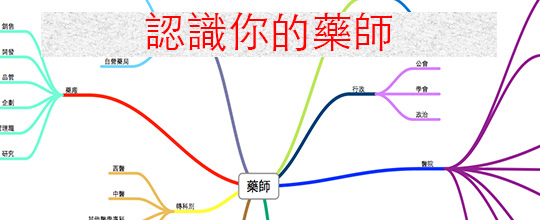

其實這是一個很值得研究的問題,對於身為台灣藥師的我們,尤其是醫院藥師,在醫院沒有重視我情況下,我們該如何強化自己的專業知識,提供病患與其他醫護人員正確的知識呢?

下面的table1會提到很多不錯的資料庫,然而這些資料庫卻所費不貲,藥師薪水又不夠多,光是買台PDA就已經很不容易,更遑論要買其下面的資料了。

Release Date: September 1, 2008 Expiration Date: September 30, 2010

Supported by an educational grant from Teva Neuroscience.

FACULTY:

Kevin A. Clauson, PharmD

Associate Professor, Pharmacy Practice

Nova Southeastern University-West Palm Beach

FACULTY DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS:

Kevin A. Clauson, PharmD, reports the following relationships to products or devices he has commercial interests related to the content of this CE activity: receives grant/research support from Elsevier and serves as a consultant for Therapeutic Research Faculty.

U.S. Pharmacist does not view the existence of relationships as an implication of bias or that the value of the material is decreased. The content of the activity was planned to be balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Occasionally, authors may express opinions that represent their own viewpoint. Conclusions drawn by participants should be derived from objective analysis of scientific data.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT:

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

Program: 430-000-08-018-H04-P; 430-000-08-018-H04-T

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

TARGET AUDIENCE:

This accredited program is targeted to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. Estimated time to complete this monograph and posttest is 90 to 120 minutes.

Exam processing inquiries:

CE Customer Service (800) 825-4696

Direct educational content inquiries to:

CE Director (800) 331-9396

DISCLAIMER:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL:

To educate clinicians on the appropriate use and interpretation of drug information databases, create awareness of the possible inaccuracies that may be present in drug information databases, and provide insight into strategies for the application of accurate information to enhance patient outcomes.

OBJECTIVES:

Upon completion of this article, the pharmacist should be able to:

1. Provide an overview of the current array of electronic resources for drug information;*

2. Discuss the manner in which information is obtained from drug databases;*

3. Discuss how inaccuracies may be present in drug information databases;*

4. Describe the pertinent terminology and concepts relative to drug information, such as contraindications, warnings, and precautions;* and

5. Discuss guidelines and strategies for appropriate interpretation of information obtained from drug databases.

*Also applies to pharmacy technicians.

|

The time in which we live is described as the Information Age, where a plethora of information beyond the wildest imagination is available at the touch of a button or, more accurately, a keypad. The advent of the Internet and the use of personal digital assistants (PDAs) allow individuals, including health care professionals, to immediately access information relevant to their needs. However, as all of this technology continues to evolve, so too does the realm of adversities associated with its advance: some of the information disseminated may not be entirely accurate. For consumers, that may not be of serious concern. But for pharmacists and other health care professionals, that concern may be critical, especially regarding information related to the use of prescription drugs. This monograph will review the types of electronic drug information clinical decision support tools (CDSTs) that are available, elucidate findings from studies that have been performed evaluating these references, create awareness of the possible inaccuracies that may be inherent in drug information databases, and provide insight into the application of accurate information. The Emergence of Clinical Decision Support Tools Whether practicing as a community or hospital pharmacist or in one of the many specialty fields of which pharmacy has now become an integral part, the availability of accurate, complete, and easy to use CDSTs is essential. One tool, the drug information database, has proven to be a great addition to the pharmacist’s arsenal. The availability of timely and accurate drug information at the point of clinical decision making has demonstrated its benefit in patient outcomes,1-6 including reduced medication errors and mortality and lower health care costs through formulary compliance. One study of systems failures revealed that the lack of drug information was most commonly blamed for observed medication errors,1 and the Institute of Medicine identified preventable medication errors as the leading cause of patient harm.2 However, compiling a drug information library can be an intimidating task for any pharmacist. At one time, practitioners had only to decide which reference book to purchase. But, with the advent of new technology that the practice of pharmacy has embraced came a reciprocal explosion of choices of electronic drug information tools. In fact, most states’ Boards of Pharmacy allow electronic drug information references to either partially or wholly satisfy the legal requirements for reference material that must be kept on hand, and some even make specific recommendations for which electronic databases they consider to be higher quality compendia.7 Another entity that has recognized the important role that electronic drug databases play in decision support is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). This agency has recognized the advantages of CDSTs and has a federally mandated reference list of drug compendia that has been proven to be broad in scope and utility for medication management of cancer patients. CMS recognizes three electronic drug information databases as authoritative references for Medicare decision making in formulary policy for anticancer chemotherapeutic regimens: AHFS DI, Clinical Pharmacology, and Micromedex DrugDex.8 Drug information databases are available in many formats, and the daunting decision about selecting which tool is appropriate to a particular practice depends on many factors. Felkey and Fox indicated that trustworthy clinical information sources must be current, complete, flexible (applied to many different situations), cost-effective, accurate (free of errors), simplistic (do not have excessive information), relevant, and of an evidenced-based nature.9 Turning to the literature for guidance and taking into consideration the target audience can help make these decisions less arbitrary. For example, in a 2004 study by Kupferberg and Hartel, the authors surveyed medical librarians, pharmacy faculty, and pharmacy students on their drug information databases preferences.10 The study participants evaluated several databases using a small set of questions and then completed a subjective survey about their experiences. The primary contributions of this study were to provide insight on practitioner preference and demonstrate the ability of five drug databases to answer ten basic drug information questions. This study is also one of the few studies to have disparate groups (ie, pharmacy faculty members, pharmacy students, and medical librarians) rate the ease of use and preferences separately, and demonstrated differing outcomes dependent on the group of interest. The study previously discussed is just one means to help choose the appropriate reference specific for the needs of the user. Another method of determination is a careful review of objective studies that have been conducted over the past several years on drug information database performance. Choosing the Platform for Your CDST Depending on the needs of the pharmacist or the practice site, drug information databases can usually be selected for one of two different platforms: 1) as an online format, or 2) for download or installation on a PDA. Online subscription databases are typically accessed through a user authentication process, such as Internet provider (IP) address verification or username and password entry. There are several non-subscription (or free) online databases also available that can be accessed by simply registering an account as well. Since online databases are housed on servers by the publisher, they are not limited by the size of the files. Consequently, this allows large amounts of data to be stored and accessed quickly and easily. Many of the subscription databases also have the ability to integrate with other pharmacy software programs making the databases even more user friendly and valuable. For those pharmacy systems that have adopted computerized physician order entry (CPOE), electronic health records (EHR), and formulary management software, several drug information database publishers have developed software that enable full integration with these applications. Integrated drug information systems allow users to access important clinical decision support at the point of order entry, to cross reference drug information contained in EHRs, and to save time and money by helping physicians comply with formulary requirements. Highlighting the Use of PDAs If a more mobile solution is necessary, drug information databases are also available to download to PDAs. These programs place important CDSTs in the hands of practitioners at the point of care. Available in both Palm OS and Windows Mobile formats, PDA versions of drug information databases can offer many of the same benefits as online drug references, including clinical decision support and formulary management. These programs are updated with varying frequency, similar to their online counterparts, and subscription purchases typically entitle the user to receive these updates by simply re-synchronizing the PDA with the host site. Some forward-thinking publishers have even begun offering patient-specific EHR review via PDAs that is fully integrated with a drug information database. To gain further insight into the capabilities of these PDAs, the reader is directed to an article published in the May 2005 issue of The Annals of Pharmacotherapy (Keplar KE, Urbanski CJ, Kania DS. Update on personal digital assistant applications for the healthcare provider. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:892-907). Because of the need for compact size and the limited memory capacity associated with PDAs, some databases have had to scale down the amount of information that is included in the PDA versions of their online databases. This has unfortunately resulted in making the drug information included in the PDA versions less complete. As technology improves and memory capabilities increase, these deficiencies will quickly vanish. Adoption of PDA use by health care providers is becoming more prevalent over time.11 In fact, when Garritty and colleagues conducted a systematic review of surveys from 1993 and 2006 examining PDA use among health care practitioners, the authors determined that this new technology is being adopted for professional use at a rate of 45% to 85%, especially among physicians. PDA technology is being embraced at a high but variable rate, and there appears to be an immediate impact on cost and training due to this trend. Another study investigated the use of PDAs among 227 nurse practitioner students and faculty who were involved in clinical practice.12 The authors reported that not only did 67% of those interviewed use a PDA, but an overwhelming 97% of those users had a drug information database installed on their device. Similarly, Barrett and colleagues determined via a survey of 88 medical residents in 2002 that the majority of those surveyed used their PDA daily to access drug information.13 International studies have highlighted the global movement toward embracing clinical tools in an attempt to improve patient care and outcomes. Most recently, a survey of 134 residents and interns practicing in Singapore revealed that 40.3% of the respondents owned a PDA. An overwhelming majority (83.3%) stated that acquisition of drug information was the primary function of their device.14 Whether the decision is made to utilize an online drug information database, its PDA counterpart, or both, most databases offer value-added features that enhance their ability to perform as CDSTs. Typically available as an additional purchase or offered free with bundled software purchases, some databases have dose and medical calculators, drug interaction checkers, and automatic substitution of formulary guidelines. Some programs offer drug identification tools that distinguish medications by their color and markings and provide pictures of the actual products as well as manufacturer contact information. Several publishers even offer software that combines patient-specific care systems with drug information, allowing practitioners to have clinical notes, laboratory results, prescription histories, and patient allergies and alerts all integrated with the latest drug information available. Interoperability and maneuverability among these features differs widely among publishers, formats, and applications. Fortunately, most publishers offer free trials or demonstrations via their website or a scheduled teleconference. Specialty CDSTs General drug information databases have, by their very nature, a broad scope of information meant to assist in decision making across a wide spectrum of practice settings. However, in dynamic fields such as complementary and alternative medicine or high-risk practices such as pediatrics, maternity, and sterile product preparation, specialized drug information is often necessary. Many publishers offer specialty drug information databases that provide practice-specific information that may not be available in a more general drug information database. These focused CDSTs are available as both online and PDA versions and are of great benefit to specialty health care providers. Unfortunately, guidance in the literature is even more ill defined for providing assistance in selecting specialty databases than it is for more general databases. Accuracy of Information in CDSTs How accurate is the information contained in drug information databases? CDSTs can only be as reliable as the information that they contain, and the information that the software contains can only be as reliable as the data used to populate it. Drug information databases are no exception. The scope, completeness, and accuracy of these references can be as varied as the references themselves. Careful, systematic, ongoing analysis of the content of drug information databases is needed in order to ensure that clinical decision making is based on the best information available to the clinician. Medication errors, adverse drug events, and inappropriate prescribing are all processes that can be positively influenced by timely access to CDSTs, but the reliability of those decisions can be greatly undermined by utilization of faulty or incomplete data. Overview of Drug Information Sources/CDSTs Several studies, both subjective and objective, have been conducted on drug information databases used as CDSTs. These studies have examined both online and PDA databases across a wide array of criteria ranging from user preference and acceptability to content analysis of scope, completeness, ease of use, and error rate. This latter type of systematic, objective study is arguably the best means to determine if these clinical decision making instruments are adequate, accurate, and reliable. In order to understand the findings of these studies, the health care provider needs a general overview of several of the more commonly employed drug information databases. This information is summarized in TABLE 1.

The first published objective online database analysis was conducted by Belgado and colleagues in 1997.15 The authors collected drug information questions posed to four decentralized hospital pharmacy sites and used a sampling of those questions to assess seven databases commonly used at that time: Drugdex, Facts and Comparison-CliniSphere, Drug Information Fulltext, Clinical Pharmacology, Lexi-Comp’s Clinical Reference Library, Physician's GenRx, and Physician's Desk Reference. The databases were assessed using an analog scale for the degree to which an answer could be provided and their ease of use. The data showed that there was no statistical difference in the ability to answer questions between Clinical Pharmacology, Drug Information Fulltext, Drugdex, and Facts and Comparisons, and the top two databases for ease of use were Drugdex and Clinical Pharmacology. No information regarding the presence or absence of erroneous answers was reported. Although the study by Belgado and colleagues is useful for its historical perspective on database performance, many of the references evaluated in that study either no longer exist or exist in another format. About five years after that trial, results from another study were published by Enders and colleagues in which the authors analyzed the performance of nine Palm OS PDA drug references for their breadth, clinical dependability, and ease of use (measured in seconds) utilizing 56 drug information questions.16 Lexi™Comp On Hand Platinum, Tarascon’s Pharmacopoeia®, MosbyDrugs, Epocrates, Davis’s Drug Guide for Physicians, PDR 2001, Physician’s Drug Handbook, A to Z Drug Facts, and mobileMicromedex were the databases examined at that time in this study. Lexi-Comp On Hand Platinum performed the best in terms of breadth and clinical dependability, whereas mobileMicromedex contained the least amount of clinical information. For ease of use, Davis’s Drug Guide was ranked highest based on time in seconds for information retrieval, and Tarascon’s Pharmacopoeia required viewing of the least number of screens to obtain an answer. Again, this study did not report whether any erroneous information was found during the analysis. In 2004, an analysis of the scope, completeness, and ease of use of ten PDA general drug information databases for the Pocket PC and Palm OS, six PDA drug interaction programs, and three PDA complementary and alternative medicine databases was conducted.17 The ten core references included were: A2z Drugs, AHFS Drug Information 2003, Clinical Pharmacology OnHand, DrDrugs, Epocrates Rx Pro, Lexi-Drugs On Hand Platinum, mobileMicromedex, 2003 Pocket PDR, Tarascon’s Pocket Pharmacopoeia, and Triple i Prescribing Guide. These references were evaluated utilizing 146 drug information questions dispersed across 14 categories that were weighted by importance. This represented both the most robust number of evaluative questions and number of references analyzed. The authors, similar to Enders and colleagues, found that Lexi-Drugs On Hand Platinum was the best overall performer in scope of information. Triple i Prescribing Guide scored highest in completeness, assessed using a three-point scale in which three represents the most complete answer. A2z Drugs was found to be the easiest to use as measured by the number of links that had to be accessed in order to find an answer.

A 2005 PDA study by Knollmann and colleagues was conducted to objectively determine the ability of the databases to provide rational prescribing decision support that was both structured and grounded in evidence-based medicine.18 The authors developed a set of novel benchmark criteria to evaluate and assess the performance of PDA drug information databases, and then they weighted these criteria based on their considered importance to practice across a 40-point scale. For example, the indications and dosing category was considered highly important and thus was assigned 10 points whereas dietary supplement information was considered least important and was thus only assigned two points. The criteria upon which all of the databases were evaluated included frequency of updates, indications and dosing, side effects, drug interactions, special features, and inclusion of information on herbs. The PDA references included for assessment were CP OnHand, ePharmacopoeia, Epocrates, mobileMDX, mobilePDR, Pepid PDC, A2z Drugs, Clin-eRX, DrDrugs, Lexi-Drugs, and PDRDrugs. The authors determined that Lexi-Drugs was the best performer with a total score of 73%. The lowest score was earned by mobilePDR, achieving only 30%. With regards to accuracy, the authors found that the databases were redolent with errors of omission, especially in the drug interactions category. In fact, there were so many errors that the authors decided to re-evaluate the PDA programs 15 months later in order to check for an improvement over time in the interaction category and found disappointing results. Only CP OnHand, ePharmacopoeia, Epocrates, and Pepid PDC were able to identify a potentially severe drug interaction that had recently been documented in a trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine. MobilePDR, mobileMDX, and ePharmacopoeia were still unable to identify drug-herb interactions. Due to the number of weaknesses identified in the databases, and the inability of the databases to provide adequate rational prescribing guidance, the authors concluded that physicians should use two or more different products as prescribing CDSTs. In a study by Peak and Girt, the authors evaluated five online drug information databases (Clinical Pharmacology, eFacts, Epocrates Rx Online, Lexi-Comp Online, and Micromedex) for dependability, completeness, and ease of use based upon 100 drug information questions divided evenly across 20 question categories.19 The authors documented how many times an answer was present, how many times an answer was absent, and how many times an erroneous answer was provided. They also tracked completeness using a scale ranging from 5 to -5 (with 5 points being subtracted for an incorrect answer) and ease of use based upon the number of screens needed to reach the answer. The authors concluded that Clinical Pharmacology was the most dependable and complete reference, and Lexi-Comp Online was the easiest to use. Again, as seen in previous studies, there were several errors detected in the answers provided. Epocrates Rx Online provided the fewest answers and was the least complete, but it did not contain any errors. The remaining databases each had errors in four categories: cost, availability, drug-herb interactions, and patient education, with a total of five wrong answers found. Two recent studies published in 2007 were the first to compare online drug information databases and their PDA counterparts.20,21 The first study analyzed online general drug information databases for their scope, completeness, and ease of use employing 158 questions divided across 15 weighted categories.20 A composite score was also calculated by weighting and combining the three evaluative facets. The study included five subscription references: Clinical Pharmacology, Epocrates Online Premium, Facts & Comparisons 4.0, LexiComp Online, and Micromedex along with two freely available references: Epocrates Online Free and RxList.com. The top performers for scope and completeness were Clinical Pharmacology, Micromedex, Lexi-Comp, and Facts & Comparisons 4.0. The easiest references to use, based on the number of steps it took to reach an answer, were the Epocrates pair. The overall top performers based on the calculated composite score were Clinical Pharmacology, Micromedex, Lexi-Comp, and Facts & Comparisons 4.0. This study reported that of the 158 questions posed across all seven databases, only three wrong answers were found. Two erroneous answers were from RxList.com and one was from Clinical Pharmacology. All incorrect information was in the dosing category, yielding an overall error rate of 0.27%. It should be emphasized that large comprehensive drug information databases, such as Micromedex and Clinical Pharmacology, had to remove substantial portions of their content in order to adapt to more limited PDA memory capacities. However, this is becoming less of a concern as PDA technology continues to improve. A simple caveat to follow is that if an answer to a drug-related question appears not to exist, it may be prudent to check the complete online drug database or to refer to the specific drug’s product information (PI) accessible at the manufacturer’s web site. The follow-up study examined the PDA versions and compared them with their online counterparts, where possible.21 Of the original seven databases included in the first study, five had directly comparable PDA counterparts: Clinical Pharmacology OnHand, Epocrates Rx Pro, Epocrates Rx Free, Lexi Comp, and mobileMicromedex. The PDA databases that performed the best for scope were Lexi-Drugs, Clinical Pharmacology OnHand, and Epocrates Rx Pro. When the composite score calculation was assessed in the same way as was done in the online comparison, Lexi-Comp was statistically superior to all other databases in this study. No PDA version performed better than its online counterpart. However, the online versions of Clinical Pharmacology and Micromedex were statistically superior in their ability to answer questions when compared with the PDA counterparts. Only one wrong answer was reported in this study of PDA databases. It was the same dosing error that was reported in the online version of Clinical Pharmacology.

Examination of Error Rates Although these aforementioned studies all show a small rate of errors in database content, there are two studies that illustrate a much different picture of the reliability of the content in these databases. Polen and colleagues conducted a study to evaluate the ability of drug information CDSTs to provide accurate and complete information for questions that arise in infectious disease-specific practice.22 In addition to the assessment of general question categories such as dosing and drug interactions, the authors also used categories specific to infectious disease practice such as emerging resistance, spectrum of activity, and synergy. Using a list of 147 questions, 14 references were assessed: 8 subscription general drug information databases (American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information, Clinical Pharmacology, Epocrates Online Premium, Facts & Comparisons 4.0 Online, LexiComp, Lexi-Comp with AHFS, Micromedex, and PEPID PDC), 5 freely accessible general drug information databases (DailyMed, DIOne, Epocrates Online Free, RxList.com, and Medscape Drug Reference), and 1 infectious disease-specific drug information database (Johns Hopkins ABX Guide). The authors discovered a total of 37 wrong answers equating to an overall error rate of 1.8%. The categories in which the errors occurred included dosing, indication, adverse drug reactions, contraindications, method of administration, and drug-food interactions. Many of the errors discovered were clinically significant and could result in patient harm, especially those found in the dosing category. The database with the highest number of errors, PEPID PDC, contained seven errors. The other errors were found in Clinical Pharmacology, DIOne, DailyMed, both versions of Epocrates, Facts & Comparisons 4.0 Online, RxList.com, Johns Hopkins ABX Guide, Lexi-Comp, and Lexi-Comp with AHFS. The remaining three databases contained no erroneous answers. A second specialty database study evaluated the content of seven PDA drug information databases designed specifically for nurses: Davis’s Drug Guide for Nurses, 2008 Lippincott’s Nursing Drug Guide, Mosby’s Nursing Drug Reference, Nursing2008 Drug Handbook, Nursing Lexi-Drugs, Prentice Hall Nurse’s Drug Guide, and Saunders Nursing Drug Handbook.23 One hundred and sixty questions were divided across 12 question categories. They were then further subdivided into two halves and comprised of general and specialty-specific questions, which encompassed geriatrics, maternity, oncology, pediatrics, and psychiatry. The error rate discovered in these references was even higher than that found in the infectious disease study. A total of 47 wrong answers were catalogued equating to a 4.2% error rate. In practical terms, this equates to wrong information being provided for 1 out of every 25 answers obtained using one of these references. Again, the highest concentration of errors was found in the dosing category, and a large number of the errors could result in clinically significant deleterious effects on patient outcomes. The highest error rate was found in Prentice Hall Nurse’s Drug Guide, which had 12 wrong answers, followed closely by Mosby’s Nursing Drug Reference, which had 10. All of the references contained some errors, with the least being reported in 2008 Lippincott’s Nursing Drug Guide. Information Sources for CDST Content When confronted with such overwhelming evidence that errors do occur in these references, an understanding of how content is developed for the databases, the types of errors that occur, and how these errors could be introduced is necessary. Publishers source their content either internally or externally and sometimes through a combination of both methods. Some publishers have in-house writers and editors that are fully responsible for designing, editing, and maintaining the content of the reference. Other publishers utilize information providers, such as Cerner Multum or First DataBank, to provide content for their drug monographs, either in whole or in part. These information brokers maintain large data sets that can be purchased and integrated into existing software interfaces and are not meant to be stand-alone references. For example, many retail pharmacies that dispense patient information leaflets along with prescriptions source the leaflet content from one of these information brokers, whereas other drug information databases generate most of their content in-house while outsourcing only their patient information or drug identification portions of the monograph. Clinicians should be aware that drug data provided by these information brokers may in themselves be inaccurate or incomplete. Clinicians should refer to additional sources to confirm information, especially the specific drug’s PI.

Types of Errors Although some errors are obviously just transcription errors or typographical errors, others arise when one section of a monograph disagrees with another section. If a drug monograph contains information in the administration section about the proper way to take a particular medication (eg, take on an empty stomach) and the patient education section contradicts this information (eg, medication can be taken with or without food), a medication error could occur. These disparities occur because one section of the monograph may be written in-house and the other section may be outsourced. While not always the case, both transcription/typographical errors and inconsistent factual errors have very real potential to lead to serious patient harm. If a typographical error occurs in the spelling of the drug name, then no harm is likely to occur, but if a typographical error occurs such as the misplacement of a decimal point in a dose, then the consequences could be catastrophic. Similarly, disagreement regarding monograph content could be insignificant or may be a cause for concern. For example, if an antiretroviral medication must be taken without food in order to keep drug levels above minimum inhibitory concentration and to prevent viral replication, and a monograph advises the patient to take with or without food, the inappropriate administration could easily lead to resistance and an unfavorable outcome. Only careful detailed editing by the publishers and objective studies such as those examined in this paper can help to highlight and consequently minimize these errors. One way that clinicians can help with the continuous quality improvement process associated with all CDSTs is to immediately report any errors they discover to the respective publisher. Database content editors, contributors, or support personnel can be emailed or contacted directly in order to address inconsistencies, questions, or gross errors. Clinicians may also want to contact the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) to report errors for possible inclusion in ISMP’s list of Textbook and Publication Errata (www.ismp.org/Errata/default.asp). Additional Insight Into Errors When considering the errors that have been reported in the previously mentioned objective, systematic studies, it is important to remember that in some instances errors were defined as occurrences when the answer provided by the database differed from that contained in the answer key used for the evaluation. Although answer keys were frequently sourced from manufacturers’ PIs and other gold standard sources, they did not necessarily mirror actual clinical practice. Thus, in these instances, the databases were not necessarily providing answers different from those found in actual practice. Another matter of interpretation that may not be reflected in these study results is that of defining a contraindication as either absolute or relative. Although FDA guidelines for defining a contraindication for prescription medications are regulated, these guidelines are not necessarily followed by the database designers. Some databases do not differentiate between types of contraindications; some classify relative contraindications as precautions or cautions, and some strictly adhere to the definitions set forth by the FDA. Standardized definitions and terminologies could help to strengthen the utility of drug information databases as CDSTs. Content Deficiencies in Drug Information Databases Unfortunately, many databases do not provide any monographs or content for complementary and alternative medicines or provide very minimal details for the most common herbs only. Other confounders in the provision of reliable drug information for herbals are the lack of standardized product formulations and lack of consistency in the safety information included on the product labeling. For example, St. John’s wort (SJW) is available in a multitude of oral formulations, including tinctures, liquids, teas, tablets, capsules, and sprays, all of which are available in a wide variety of concentrations. In addition to these single-source items, SJW is also a component in hundreds of combination products marketed internationally. Because of variations such as these, health care providers should always consult multiple sources when answering questions about herbal products. If possible, a database that concentrates on complementary and alternative medicine, such as the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database or Natural Standard, should be at least one of the sources consulted. It should be noted that drug information databases generally contain ample content. However, an area that could be enhanced would be the provision of reference sources. It would be helpful to clinicians if databases routinely included the complete reference source from where the drug information was obtained. This would be especially beneficial for clinicians in the evaluation process, particularly if the source was indicated to be a primary reference, a secondary or tertiary reference, or was from a case report or clinical trial. Guidelines and Strategies The appropriate and clinically responsible application of CDSTs is essential to patient safety. Recognizing that the information found in electronic drug information databases is not always 100% reliable is the first step in understanding the role of drug information databases in decision support. Health care providers should rely on training and clinical experiences to guide their use of these tools. In certain specialties and patient populations, it is crucial that health care providers consult more than one reference in order to help establish the validity of the information, especially for dosage questions. In patients who are both very young and very old, accurate dosing parameters are not always provided by the manufacturers due to a lack of clinical trials in these populations. For geriatric and pediatric patients, appropriate doses are typically established through practical application. These “established” doses are in turn adopted as guidelines by the professional organizations that specialize in these populations. For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics provides guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of asthma in children that may not agree with the FDA-approved dosing parameters for those medications. When a health care provider consults a drug information database, it is possible that the FDA-approved dose may be provided, the clinically recognized dose may be provided, both dosages may be provided, or no dose may be provided for special populations. It is imperative that multiple sources are consulted, and health care providers must be certain that they know and understand the origin of the information that the monograph is providing. If clinical guidelines follow off-label dosing, then that information will not be provided in monographs sourced exclusively from manufacturers’ package inserts. Another critical arena that merits a careful review of at least two references is questions concerning complementary and alternative medicine. Again, because of the lack of randomized controlled trials and FDA regulations, this class of pharmacologically active agents often has conflicting information amongst databases. Some drug information resources provide referenced monographs so that the validity of the information can be confirmed by the primary literature. This also allows the health care provider to determine the strength of the recommendations independently. Conclusion Overall, of the studies that assessed and reported the accuracy of the general online and PDA drug information database CDSTs, the data indicate these references generally provide reliable and safe clinical information. However, these studies also show that no database is correct 100% of the time. In particular, the data from the specialty database studies raise questions about the reliability and validity of the database content. It is important for clinicians to understand that drug information brokers and publishers of drug information databases may provide data that are not accurate or complete. Therefore, it is imperative for clinicians to refer to more than one source, including the specific drug’s PI. Although no CDST should ever substitute for appropriate education and clinical judgment, the right drug database can be an invaluable asset for any health care provider who needs timely, accurate, and easy-to-access information. This is especially true if the references are carefully chosen to reflect the specific needs of the pharmacist or practice setting. REFERENCES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢