Bethany Nickerson, PharmD, BCPS Clinical Pharmacy Specialist Health Alliance Plan of Michigan Detroit, Michigan

9/21/2009

US Pharm. 2009;34(9):49-55.

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is characterized by chronic widespread pain, multiple tender points, abnormal pain processing, sleep disturbances, profound fatigue, and psychological distress.1 It is recognized as one of the most common chronic widespread pain syndromes, affecting approximately 2% of the U.S. population.2 The presence of fibromyalgia is seven times more common in women than in men.2 This mysterious condition has a history of controversy, with some people questioning whether it is a disease at all. Fibromyalgia draws skepticism for reasons including lack of a known cause, lack of tests to confirm the diagnosis, and an overlap of symptoms with other conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome and other pain disorders.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of FMS is not related to peripheral musculoskeletal changes, but rather to abnormalities of the central pain processing mechanism that result in central pain sensitization.3 Patients with FMS have lowered mechanical and thermal pain thresholds, high pain ratings for noxious stimuli, and altered temporal summation of pain stimuli.4

Pain perception is the result of a bidirectional process of ascending and descending pathways.5 Nociceptive input from peripheral afferent neurons is sent via the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to the higher brain centers involved in pain perception. Some descending inhibitory projections to the spinal cord attenuate the nociceptive effects. Numerous neurotransmitters including serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and substance P are involved in these processes. Other pathways in the brain involve the same neurotransmitters that affect mood control, sleep regulation, and cognitive function. This accounts for the wide range of symptoms seen in fibromyalgia.5

Diagnosis

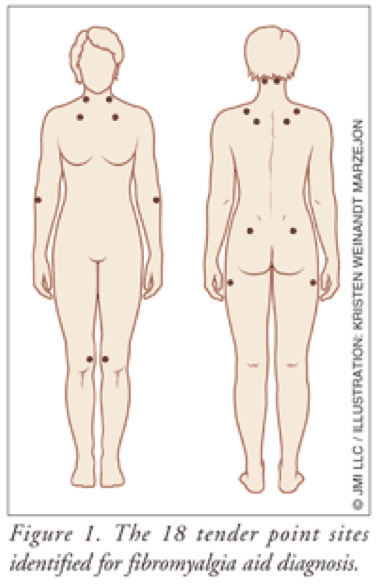

Despite the controversy surrounding fibromyalgia, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published criteria for the diagnosis almost 20 years ago. This development of diagnostic criteria has enabled practitioners to distinguish fibromyalgia from other forms of chronic pain. Diagnosis is made through physical examination. Criteria for classification of fibromyalgia include widespread aching pain for at least 3 months. Pain must be on the right and left side of the body and above and below the waist. In addition, palpable pain with mild, firm pressure must be present in at least 11 of 18 identified tender point sites (FIGURE 1).6

Symptoms of other rheumatic disorders can overlap with those of fibromyalgia (e.g., tendonitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis), making diagnosis more difficult. Some clinicians with experience in fibromyalgia do not feel that the ACR criteria are sufficiently reliable and have begun to consider other aspects of the disease; however, no consensus has yet been reached as to the validity of these additional criteria.7

Treatment Overview

Because the exact cause of fibromyalgia is unknown, treatment can be difficult. Treatment of pain is often considered most important, taking precedence over physical or psychological symptoms.8 Effective therapy varies from patient to patient and is often a matter of trial and error. About 90% of fibromyalgia patients seek alternative or complementary therapies, often in the form of natural medicines.9 The number of published studies, particularly randomized controlled trials, has risen steadily over the past decade. Treatment remains inadequate to reliably resolve persistent symptoms and improve functional limitations and quality of life in most patients.

One reason for unsatisfactory outcomes may be the absence of an evidence-based standard of care. To address this void, a recent report commissioned by the American Pain Society (APS) provides a comprehensive assessment of the research supporting treatment choices for the patient with fibromyalgia and presents clinical practice guidelines.10 These guidelines underscore the importance of holistic and multidisciplinary management of the syndrome by using both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies including relaxation techniques, physical therapy, biofeedback, and other cognitive therapies.

Pharmacologic treatment of fibromyalgia historically targeted pain with opioids or muscle relaxants, depression with antidepressants, and sleep with anxiolytics or hypnotics. As our understanding of fibromyalgia broadens, more specific pharmacologic treatment is being investigated and developed for these patients. Several agents from various drug classes have been shown to relieve fibromyalgia-related pain. The drugs used have different mechanisms of action, but many interfere with neurotransmitter release or uptake in the brain.

Various treatment approaches for fibromyalgia are summarized in TABLE 1.

Treatment With Antidepressants

More than 500 randomized controlled trials have tested the effectiveness of various drugs in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Based on these, the evidence-based guidelines of the APS and the recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) on the management of fibromyalgia gave the highest level of recommendation to antidepressants (TABLE 2).10,11 All antidepressants in the United States carry a black box warning regarding the risk of suicide.12

Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs): TCAs are among the oldest antidepressants on the market. They work by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, increasing the synaptic concentrations in the central nervous system (CNS), thus reducing pain signaling. A recent meta-analysis showed strong evidence for the efficacy of amitriptyline in reducing pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances; evidence also exists for short-term benefit of cyclobenzaprine.13 Cyclobenzaprine is used as a skeletal muscle relaxant, not an antidepressant; however, structurally it is a TCA and can be used as such in fibromyalgia. Although TCAs are highly effective, they are also associated with more severe side effects than newer antidepressant medications.14 Side effects include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, fatigue, and low blood pressure. People with glaucoma, heart conditions, or seizure disorders should avoid TCAs.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): SSRIs work by blocking the action of the presynaptic serotonin pump, thereby increasing the amount of serotonin available in the synapse and increasing postsynaptic serotonin receptor occupancy. A recent meta-analysis showed evidence for the efficacy of the SSRIs fluoxetine and paroxetine in reducing pain.13 The effects were small on depressed mood and health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and they had no effect on fatigue. SSRI side effects are generally mild and include nausea, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and headaches.13

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): Like TCAs, SNRIs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine; however, they have little to no interaction with muscarinic, histaminic, or adrenergic receptors, making their side-effect profile much more benign. Although the exact mechanism is not known, it is believed that the effects of SNRIs on depression, anxiety symptoms, and pain perception are due to increasing the activity of serotonin and norepinephrine in the CNS.13 Currently, there are two SNRIs approved in the U.S. for fibromyalgia: duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella). (These agents will be discussed in further detail later.) No placebo-controlled studies with venlafaxine in fibromyalgia have been identified.

Analgesic Medications

For pain relief, analgesics are effective for some patients. Tramadol, with or without acetaminophen, has been effective in patients with FMS.15-17 Tramadol is a centrally acting opioid analgesic that exerts its effect through the binding of parent drug and M1 metabolite to mu-opioid receptors and through the weak inhibition of nor epinephrine and serotonin reuptake. Tramadol should be used with caution due to the possibility of typical opiate withdrawal symptoms with discontinuation and the risk of abuse and dependence.

Opioids are not recommended due to significant side effects (e.g., sedation, respiratory depression, impaired cognition, nausea and vomiting, constipation), the potential for dependence and abuse, and lack of controlled trials in patients with FMS; opioids should only be considered after all other medicinal and nonmedicinal therapies have been exhausted.10

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be useful as adjunctive therapy; however, there is no evidence that they are effective when used alone in FMS. This is probably because fibromyalgia pain is not due to an inflammatory process.10

Anticonvulsant Medications

The alpha2-delta ligands gabapentin and pregabalin are effective in FMS.18,19 Gabapentin is a structural analogue of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and has been found to have analgesic effects in randomized, controlled clinical trials in diabetic neuropathy, post herpetic neuralgia, migraine prophylaxis, and other neuropathic pain conditions. It is hypothesized that the antinociceptive effects of gabapentin are mediated by modulation of calcium channels via alpha2-delta ligand binding, modulation of transmission of GABA, and possibly other additional unidentified mechanisms. In FMS, gabapentin is effective when used with a dosage range of 1,200 to 2,400 mg per day.19 Pregabalin shares the same mechanism of action of gabapentin; however, the pharmacokinetic profile demonstrates a more linear dose-response relationship. Up to 450 mg per day of pregab alin is approved for use in fibromyalgia. Patients taking gabapentin or pregabalin may experience fatigue, sedation, nausea, drowsiness, dizziness, and weight gain.18,19 Pregabalin will be discussed in more detail below.

FDA-Approved Medications

There are currently three drugs that are FDA approved for the management of fibromyalgia: pregabalin (Lyrica), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and milnacipran (Savella) (TABLE 3).

Pregabalin: Although ACR criteria date back to 1990, it was not until 2007 that the FDA approved the first medication for the management of fibromyalgia. On June 21, 2007, pregabalin was approved based on results from two double-blind, controlled clinical trials, involving about 1,800 patients with fibromyalgia.20,21 The ACR criteria are the basis of diagnosis of patients enrolled in the studies. Compared to placebo, doses of pregabalin (300-450 mg/day) were significantly more effective in reducing pain scores. Pregabalin was also associated with decreased fatigue and improved sleep and HRQOL.

Pregabalin is a 3-substituted analogue of GABA that binds selectively to the alpha2-delta subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel. Its exact mechanism of action is not known but may be due to the reduction in the release of several neurotransmitters resulting in analgesic, anticonvulsant, and anxiolytic effects. Based on the clinical trials, dosing should start with 75 mg twice daily, increased to 150 mg twice daily within a week. For patients with inadequate relief on 150 mg twice daily, it is recommended to increase to 225 mg twice daily. Doses higher than this were no more effective in clinical trials and were associated with more adverse effects. The most common side effects are dizziness and somnolence.20,21 Pregabalin is also FDA approved for the treatment of seizures, postherpetic neuralgia, and pain due to diabetic peripheral neuropathy.22

Duloxetine: On June 16, 2008, duloxetine became the second FDA-approved drug for the management of fibromyalgia. Duloxetine is also approved for neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy and depression in adults.23

Duloxetine is a potent SNRI and a less potent inhibitor of dopamine reuptake. The exact mechanism of action is unknown, but it is believed that its effects on depression, anxiety, and pain perception may be due to increased activity of serotonin and norepinephrine in the CNS. The FDA approved duloxetine for the management of fibromyalgia based on two 3-month randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials involving 874 patients with fibromyalgia (based on ACR criteria).24,25 In both studies, duloxetine was shown to reduce pain, and the degree of pain reduction was greater in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder. Dosing should start with 30 mg once daily for 1 week and increase to 60 mg daily. Doses greater than 60 mg daily were no more effective and were associated with a higher rate of adverse effects. The most commonly reported adverse effects were nausea, dry mouth, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, somnolence, decreased appetite, and hyperhidrosis.24,25

Milnacipran: Milnacipran was approved by the FDA on January 14, 2009, for the management of fibromyalgia. Milnacipran is an SNRI that has been used since 1997 in parts of Europe and Asia for the treatment of depression. Currently, its only indication in the U.S. is for the management of fibromyalgia. Like duloxetine, milnacipran is an SNRI with an unclear mechanism of action.26

Both open-label and double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have confirmed the efficacy of milnacipran in FMS, not only on the pain component but also on the fluctuating array of other symptoms such as sleep and cognitive disturbances and fatigue. The phase III trials have comprehensive composite end points to capture the many complex domains of FMS.27,28 Milnacipran demonstrated durability of response for up to 1 year. Dosing should start with 12.5 mg once daily and be titrated to a recommended dose of 100 mg/day (50 mg twice/day) without regard to food. Based on individual patient response, the dose may be increased to 200 mg/day (100 mg twice/day); doses above 200 mg/day have not been studied. The most common reported adverse reactions (≥5% and more than placebo) in clinical trials were nausea, headache, constipation, dizziness, insomnia, hot flush, hyperhidrosis, vomiting, palpitations, increased heart rate, dry mouth, and hypertension.26

Conclusion

Fibromyalgia is a common and disabling syndrome with pain being the primary presenting symptom and pain relief the principal concern of patients. Once a diagnosis has been established, it is important to select appropriate pharmacologic treatment. TCAs are generally considered first-line therapy; however, if they are ineffective or intolerable due to side effects, there are more options now than ever before. The development of new drugs for fibromyalgia is the result of a better understanding of the chronic pain mechanisms involved in this condition. Clinical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of therapies targeting central pain mechanisms, such as alpha2-delta ligands (gabapentin, pregabalin) and SNRIs (duloxetine, milnacipran). Once an effective pharmacologic treatment is found, it is imperative to pursue nonpharmacologic options such as education, exercise, and cognitive behavior therapies, because an integrated treatment plan will benefit patients more than just medications alone.

REFERENCES

1. American College of Rheumatology. Patient education for fibromyalgia. www.rheumatology.org/public/ factsheets/diseases_and_ conditions/fibromyalgia.asp? aud=pat. Accessed March 25, 2009. 2. Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, et al. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:19-28. 3. Bennett R. Fibromyalgia: present to future. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:371-376. 4. Diers M, Koeppe C, Yilmaz P, et al. Pain ratings and somatosensory evoked responses to repetitive intramuscular and intracutaneous stimulation in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Clin Neurophys. 5. Stahl SM. Fibromyalgia—pathways and neurotransmitters. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2009;24(suppl 1):S11-S17. 6. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunun MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 7. Perrot S, Dickenson AH, Bennett RM. Fibromyalgia: harmonizing science with clinical practice considerations. Pain Pract. 2008;8:177-189. 8. Staud R. The abnormal central pain processing mechanism in patients with fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia Frontiers. 2002;10:18. 9. Ernst E. Usage of complementary therapies in rheumatology: a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol. 10. Buckhardt CS, Goldenberg D, Crofford L, et al. Guideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome pain in adults and children. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2005. http://guidelines.gov/summary/ 2008;25:153-160. 1990;33:160-172. 1998;17:301-305. summary.aspx?doc_id=7298&nbr= 004342&string=fibromyalgia. Accessed March 25, 2009. 11. Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:536-541. 12. Revisions to product labeling. Suicidality and antidepressant drugs. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ DrugSafety/ InformationbyDrugClass/ UCM173233.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2009. 13. Hauser W, Bernardy K, Uceyler N, Sommer C. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:198-209. 14. Nishishinya B, Urrutia G, Walitt B, et al. Amitriptyline in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review of its efficacy. Rheumatology. 2008;47:1741-1746. 15. Russell IJ, Kamin M, Bennett RM, et al. Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J Clin Rheumatol. 2000;6:250-257. 16. Bennett RM, Kamin M, Karim R, et al. Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med. 2003;114:537-545. 17. Bennett RM, Schein J, Kosinski MR, et al. Impact of fibromyalgia pain on health-related quality of life before and after treatment with tramadol/acetaminophen. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:519-527. 18. Lyseng-Williamson KA, Siddiqui MA. Pregabalin: a review of its use in fibromyalgia. Drugs. 2008;68:2205-2223. 19. Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Stanford SB, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1336-1344. 20. Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1264-1273. 21. Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Arnold LM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of pregabalin in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:502-514. 22. Lyrica (pregabalin) package insert. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc.; April 2009. 23. Cymbalta (duloxetine) package insert. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Co.; February 2009. 24. Arnold LM, Lu Y, Crofford LJ, et al. A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2974-2984. 25. Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain. 2005;119:5-15. 26. Savella (milnacipran) package insert. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; March 2009. 27. Clauw DJ, Mease P, Palmer RH, et al. Milnacipran for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults: a 15-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1988-2004. 28. Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Gendreau RM, et al. The efficacy and safety of milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:398-409.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢