Finasteride lowered the incidence of detected prostate cancer but did not improve survival.

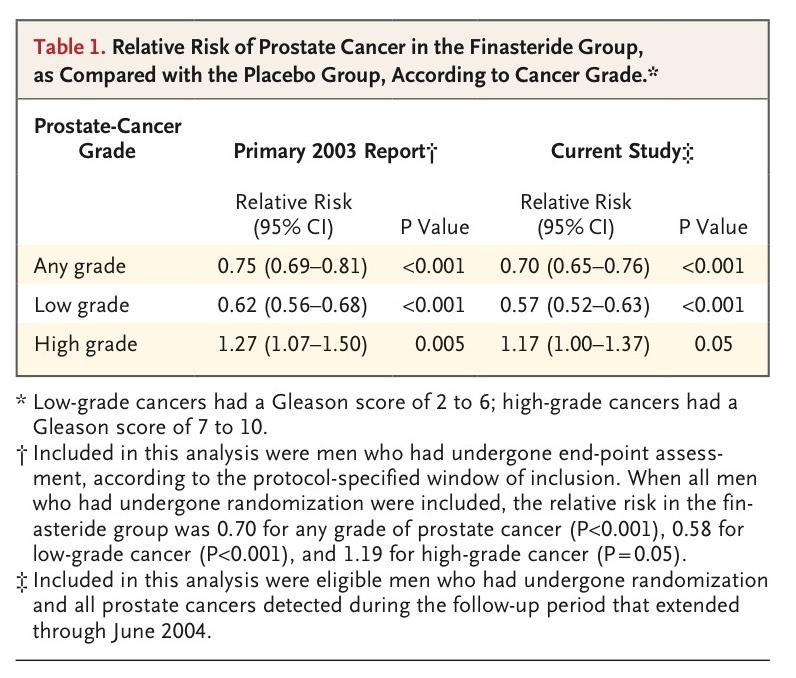

To determine whether finasteride (Proscar and generics) prevents prostate cancer, 19,000 men received finasteride or placebo for 7 years in the randomized Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. The initial findings were published in 2003: Fewer prostate cancers overall — but more high-grade cancers — were detected in the finasteride group (NEJM JW Gen Med Jul 18 2003). Some authors speculated that the apparent increase in high-grade cancers was spurious — an artifact of finasteride-induced prostate shrinkage, which enabled easier detection of high-grade cancers in random biopsy samples (NEJM JW Gen Med Oct 11 2007).

Now, the researchers offer additional posttrial follow-up data, focused on survival after randomization. Estimated 15-year survival rates were virtually identical in the finasteride and placebo groups. In addition, among men in whom prostate cancer was diagnosed, estimated survival was similar in the finasteride and placebo groups. Because cause-of-death information was unavailable for many men, prostate cancer–specific mortality was not assessed.

COMMENT

If the overall reduction in prostate cancer incidence had been clinically important, survival should have improved in the finasteride group. In contrast, if finasteride truly had induced more aggressive cancers, survival should have decreased in the finasteride group. In fact, neither of these outcomes occurred: Survival was the same in the finasteride and placebo groups. Although the absence of information on prostate cancer–specific mortality is a limitation, these findings argue against using finasteride for chemoprevention of prostate cancer.

Allan S. Brett, MD reviewing Thompson IM et al. N Engl J Med 2013 Aug 15.

你可以另外參考以下這兩篇:

A Role for Finasteride in the Prevention of Prostate Cancer?

All medical care should seek to achieve one or more of these three goals: to relieve suffering, to prevent future suffering, or to prolong life. Preventive services, by definition, are utilized to prevent future suffering or prolong life. We should offer preventive services when science assures us that across the population of patients we serve, we do more good than harm.

How would we know if a preventive service accomplishes one or more of these three goals? All-cause mortality is the most appealing outcome in a prevention trial because it clearly reflects the goal of prolonging life, and it is not subject to the difficulties of accurately assigning a specific cause of death. All clinicians who struggle with completing a death certificate can identify with the challenge that researchers face in the ascertainment of cause of death. But at any specific age, most single diseases play a relatively small role in overall mortality. It is much easier to demonstrate a reduction in disease-specific mortality.

Prostate cancer is a logical target for a preventive service, with most of the public discourse about prostate-cancer prevention today focusing on screening. Screening seeks to identify cancers in asymptomatic persons with the hope of altering the natural history of those cancers that are destined to cause suffering without doing too much harm in the process. In the multicenter Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial1 conducted in the United States, there was a nonsignificant increase in prostate-cancer mortality in the screening group, though the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial2 showed a statistically significant absolute reduction of 0.10 prostate-cancer deaths per 1000 person-years after a median follow-up of 11 years. In the latter trial, all-cause mortality was 19.1% in the screened group and 19.3% in the control group, a difference that was not significant. Unfortunately, this reduction occurred in the context of a significant increase in the number of cancers diagnosed and treated in the screened group.

Much of the morbidity resulting from prostate cancer is a consequence of the diagnosis and management of the disease, rather than the disease itself, and many screen-detected cancers would never become apparent in the lifetime of the patient in the absence of screening. It was the judgment of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (on which I served) that the potential benefit of screening for prostate cancer by measuring prostate-specific antigen (PSA) does not outweigh the harms.3

It is against this background that primary prevention has much appeal. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT)4 was a landmark study that sought to reduce the morbidity and mortality of prostate cancer with the use of finasteride to prevent the disease. Using the incidence of cancer as a proxy for morbidity and mortality, the trial investigators found a significant reduction in the diagnosis of prostate cancer among men receiving finasteride but unfortunately also a small increase in the number of high-grade cancers. Several biases have been identified to explain this increase,5 but concern for harm remains.

In this issue of the Journal, Thompson et al.6 seek to allay that concern by examining long-term all-cause mortality among PCPT participants. The results are reassuring, with an overall 15-year rate of death of 22% in both the finasteride group and the control group. The investigators were unable to report prostate-cancer–specific mortality, and as noted in the results of the ERSPC trial, a small difference in prostate-cancer mortality can exist in the absence of a difference in all-cause mortality.

What can we now conclude about the use of finasteride for prevention? The safest conclusion is that it has no short- or long-term effect on all-cause mortality, so we cannot recommend its use to prolong life. What about the prevention of future suffering? When interpreting the results of the PCPT, it is important to note that both the finasteride and placebo groups were being actively screened for prostate cancer. The USPSTF noted that “the decision to initiate or continue PSA screening should reflect an explicit understanding of the possible benefits and harms and respect the patients' preferences.”3

For men who choose regular prostate-cancer screening, the use of finasteride meaningfully reduces the risk of prostate cancer and thus the morbidity associated with treatment of the disease. Whether the use of the drug has either a positive or a negative effect on prostate-cancer–specific mortality remains unknown, but either way the effect is probably very small and does not result in any difference in life expectancy. Men who are aware of and understand the benefits, risks, and uncertainties associated with the use of finasteride for prevention may make a rational decision to take the drug to reduce the harm of screening. Of course, another way to reduce the harm of screening is to choose not to be screened.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢