安非他命、古柯鹼、MDMA (快樂丸、搖頭丸)這一類的毒品對心臟血管系統的危害主要是經由興奮交感神經系統所引起。交感神經系統的興奮會引起心跳加快及週邊血管收縮,但是對血壓的影響則較難預料。週邊血管收縮可能導致血壓急速上升,也可能因為交感神經傳遞物質耗盡或毒品直接抑制心臟功能而造血壓下降。血壓的急速變化會引起血管內膜及內皮細胞受傷,加速動脈粥狀硬化的進行,甚至導致冠狀動脈或主動脈剝離的重大併發症。古柯鹼容易引起心臟冠狀動脈痙攣,血小板凝集及血栓形成導致心肌梗塞而造成死亡。此外,各種致命性的心律不整皆可能發生。

Journal of Cardiac Surgery Sep-Oct 2007;22(5):390-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2007.00432.x.

Elizabeth Wako, M.D., Denise LeDoux, A.R.N.P., Lee Mitsumori, M.D., and Gabriel S. Aldea, M.D. Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Washington, AA-115 Health Sciences Building, 1959 NE Pacific Street, Seattle, Washington ABSTRACT The clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of six consecutive patients presenting with acute aortic dissection secondary to hypertensive crises from methamphetamine use is described. Data were obtained prospectively from the expanded STS clinical database of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Washington, but reviewed in a retrospective fashion. These patients represent 5.5% of all patients diagnosed and treated for aortic dissection in the same time period (6/109) and 20% of all patients with aortic dissection under the age of 50 years (6/30). We conclude that young patients presenting with acute aortic dissections should be routinely tested for methamphetamine. Positive urine tests should be confirmed with chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Beta and alpha blockers should be used instead of the more typical beta blockade alone. We recommend the addition and documentation of intense, long-term drug rehabilitation program along with routine periodic clinical and radiographic follow-up to prevent secondary aneurysmal dilation of remaining pathological aorta

Twelve million Americans (5.3% of the population) report using methamphetamine.1 Methamphetamine is a derivative of amphetamine, a central nervous system stimulant that has dramatically increased in use over the past 10 years in the western, southwestern, and mid-western United States, with its greatest popularity in the 26-34 age groups. The use of methamphetamine has been associated with the development of profound hypertensive states with reports of ruptured berry aneurysm and cardiomyopathy but has not been specifically noted with thoracic aortic dissections. This report summarizes experience with five such consecutive methamphetamine-related aortic dissection treated in the past two years. METHODS Clinical data of all patients presenting to the Cardiothoracic Surgery division of the University of Washington are collected prospectively in an expanded Society of Thoracic Surgery format and database. A retrospective review of these data and medical records was performed for chemically confirmed methamphetamine use and clear-cut computerized tomography (CT) evidence of acute aortic dissection.

RESULTS

Case 1: 39-year-old male admitted February 2002 with acute right flank and chest pain. Patient described extensive use of methamphetamine for past three days prior to presentation. Blood pressure on admission was 160/90. CT scan showed a Stanford type A aortic dissection beginning in the proximal ascending aorta extending into the right common femoral with no perfusion to the left kidney. The patient underwent urgent surgical repair, admission to intensive care unit (ICU),

and eventual discharge in stable condition.

Case 2: 37-year-old male admitted September 2002 with two days of acute abdominal pain. Presenting blood pressure was 141/88 on esmolol drip. Past medical history was significant for hypertension and congestive heart failure. The patient had a urine toxicology screen that was positive for methamphetamine and admitted to polysubstance abuse. CT scan showed a Stanford type B aortic dissection from just past the left subclavian extending to the aortic bifurcation. Clinical examination demonstrated no evidence of visceral or lower extremity malperfusion. The patient was admitted to the ICU, alpha blockade was added, and the patient was stabilized. Patient recovered uneventfully with medical management and is stable at follow-up.

Case 3: 38-year-old male admitted May 2004 with back pain. Past medical history was significant for hypertension. Initial blood pressure at outside hospital was systolic 220, upon arrival with nipride and esmolol drips blood pressure was 121/78. Urine toxicology done in the emergency room was positive for methamphetamine. CT scan showed a Stanford type B dissection with extension into the iliac arteries bilaterally with no perfusion to his left renal artery, secondary to a false lumen. He underwent aortic fenestration in Interventional Radiology and a femoral-femoral artery bypass to reestablish perfusion to his right lower extremity. His hospital course was complicated by acute renal failure, cerebrovascular accident, and a right pseudoaneurysm. He was eventually discharged from the hospital in good condition.

Case 4: 35-year-old male admitted July 2004 with acute left arm and neck pain with discrepancies in upper extremity blood pressures. By report from outside hospital, systolic pressure was right arm 120 and left arm 80. On admission initial blood pressure was 102/70. Past medial history was significant for an inherited muscular disorder. Patient had a urine toxicology screen positive for methamphetamine. CT scan showed a Stanford type A dissection with a false channel extending from the aortic root into the transverse aortic arch, with the descending aorta free of dissection. The patient was taken to the operating room for emergent resection of the ascending aorta and replacement with graft and resuspension of the aortic valve.

His postoperative course was complicated by breakdown of his native aortic tissue proximal and distal to the suture line requiring emergent repair with a redo root modified Bental procedure and ascending aortic proximal arch re-replacement. The patient continued to be unstable and eventually died as a complication of his disease.

Case 5: 44-year-old male admitted September 2004 with transient left eye blindness and persistent chest pain. Past medical history was significant for hypertension and seizure disorder. Presenting blood pressure was 110/80. The patient had a urine toxicology screen positive for methamphetamine. CT scan showed an enlarged ascending aorta as well as a Stanford type A aortic dissection extending from the ascending through the descending thoracic aorta. The patient was taken to the operating room for aortic valve resuspension and replacement of ascending aorta. The remainder of his hospital course was uneventful and the patient was discharged in good condition.

Case 6: 44-year-old male admitted January 2006 with severe substernal chest pain and epigastric abdominal pain. Past medical history was significant for hypertension, COPD, gout, obesity, and anxiety. Presenting blood pressure on nipride was 145/98. Patient had a urine toxicology screen positive for methamphetamine. CT scan showed a Stanford type A ascending aortic dissection. Patient was taken emergently to the operating room for aortic valve resuspension, replacement of ascending aorta with a woven Velour 30 mm Dacron graft. Postoperative course was complicated by mental status changes that cleared by discharge. He was eventually discharged from the hospital in good condition.

CONCLUSIONS

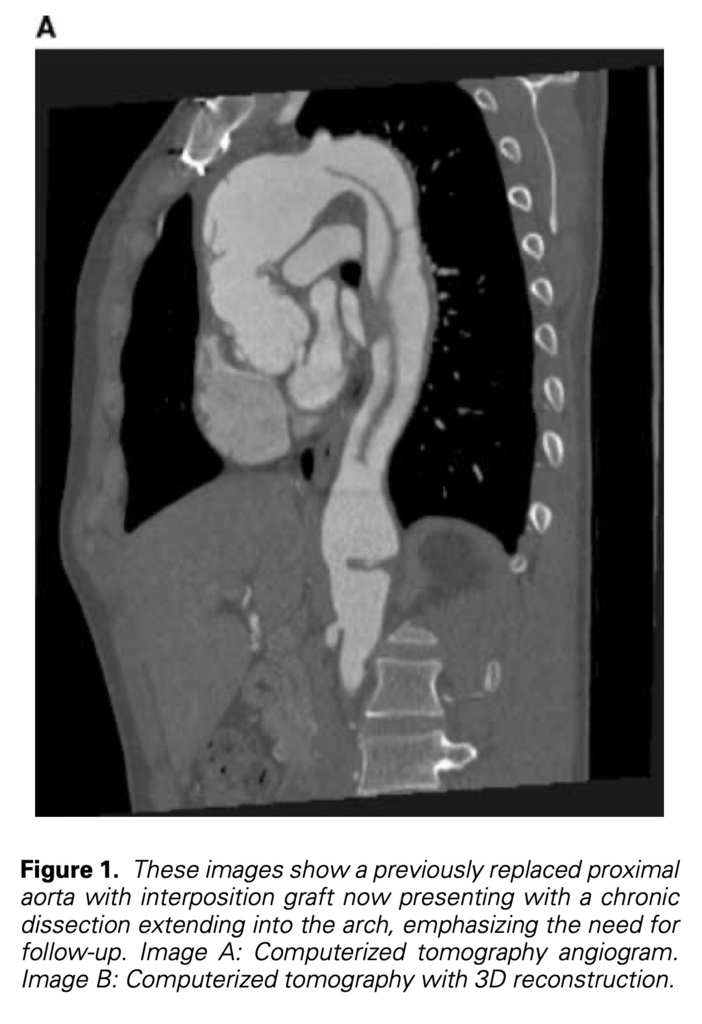

The incidence of methamphetamine use continues to increase dramatically as evidenced by the growing number of methamphetamine seizures, arrests, indictments, and sentences.2 We therefore expect and anticipate an increase in both overt and subtle complications related to the use of this drug and the hypertensive crisis associated with its use. Aortic dissections typically occur secondary to a tear of aortic intimal due to degeneration of the aortic media.3 This is felt to be exacerbated by acute systemic hypertension as demonstrated by the Mayo clinic experience showing that 78% of patients with aortic dissection presented with hypertension.4 Because of the massive hypertensive crisis associated with methamphetamine use, we would expect to see an increase in the incidence of catastrophic acute aortic events presenting in young patients without clear stigmata of connective tissue, inflammatory or aortic root disorders (such as Marfan’s syndrome, aortitic or vasculitic conditions or bicuspid aortic pathology with annular aortic ectasia). Several important issues need to be discussed regarding this patient population. First, the need for accurate testing and diagnosis. The etiology of aortic aneurysm in young adults is typically related to a collagen disorder or inflammatory disease causing vasculitis. Appropriate diagnosis commits the patient to long-term follow-up of the entire aorta to assess pathological dilatation of currently unaffected segments and focus on genetic screening and evaluation (echo, CT) of the entire family to rule out hereditary or congenital disorders. Many patients with acute aortic dissection manifest hypertension or differential blood pressure between upper or upper and lower extremities. Hypotension can also occur in association with tamponade. Although hypertension is common in these patients, massive hypertensive episode especially in the absence of stigmata of connective tissue disorder does not always raise the concern of other etiologies such as occult methamphetamine use. Since many patients are referred to regional cardiac surgical centers from hospitals on appropriate intravenous antihypertensive therapy, the magnitude of the hypertensive crises and the clinical suspicion of methamphetamine use as a possible causative agent may be missed. In our small series, only 1/6 patients manifested presenting pressures of >160/100 mmHg on arrival to our center. Since methamphetamine is an illegal substance, most patients are unwilling to freely mention this use in an admitting history and physical. Specific drug use history should be individually addressed with each patient. We also suggest a careful detailed physical examination looking for evidence and stigmata of methamphetamine use such as dry itchy skin, premature ageing, rotting teeth, acne, and sores. Most importantly we recommend that routine methamphetamine testing in urine should be done on all patients on admission to more accurately identify this problem. It is essential to follow all positive urine tests with a detailed medication history and subsequent confirmatory tests since many legal (including over the counter) drugs can cause a false positive urine screen for the presence of methamphetamine. All positive urine test screens should therefore be confirmed with a definitive chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), a standard set by the federal government for work place drug screening.5 Second, medical management should be altered for patients with confirmed or suspected methamphetamine use. The standard treatment for patients with acute dissection is intravenous beta-blocking agents6 such as esmolol. Studies have shown that interaction with methamphetamine and metoprolol can lead to unpredictable results due to similar metabolism.7 Furthermore, the alpha stimulating effect of this drug is unaffected by the blocking agents and is unabated. Alternatively we recommend use of agents that combine alpha and beta blockade such as labetolol. Third, careful follow-up is essential in patients with methamphetamine-associated dissections. Follow-up should focus on counseling, strict drug rehabilitation, and abstinence programs (with appropriate monitoring of compliance), along with chronic antihypertensive medical management and careful periodic clinical surveillance with appropriate imaging (most commonly CT angiograms) to identify earlier secondary aneurysmal dilation of remaining dissection and pathological aorta (Fig. 1). We reviewed our experience with six patients presenting with methamphetamine-associated acute aortic dissections and identified an unusual but not unanticipated association between the use of this drug, hypertensive crisis, and acute aortic dissection. Based on our limited but growing experience, we recommend that: 1. Younger patients (age < 50 years old) presenting with acute aortic dissections should be tested routinely for methamphetamine, especially in the absence of stigmata of connective tissue disorders. 2. Positive urine tests should be confirmed with GCMS. 3. Beta and alpha blockage should be used for acute hypertension control instead of pure beta blockade. 4. Routine drug rehabilitation should be offered and documented with long-term clinical and radiographic screening to prevent secondary aneurysmal dilation of remaining dissection.

REFERENCES

1. Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, et al: History of the methamphetamine problem. J Psychoactive Drugs 2000;32:137-141.

2. Facts & Figures: Methamphetamine. White house office of national drug control policy. Drug Policy Information Clearinghouse, Rockville, 2006.

3. Larson EW, Edwards WD: Risk factors for aortic dissection: A necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol 1984; 53:849-855.

4. Spittell PC, Spittell JA, Jr, Joyce JW, et al: Clinical features and differential diagnosis of aortic dissection: Experience with 236 cases (1980 through 1990). Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68:642-651.

5. Goldberger BA, Cone EJ: Confirmatory tests for drugs in the workplace by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 1994;674:73-86.

6. Elliot WJ: Clinical features and management of selected hypertensive emergencies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2004;6:587-592. 7

. Lin LY, Di Stefano EW, Schmitz DA, et al: Oxidation of methamphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine by CYP2D6. Drug Metab Dispos 1997;25:1059-1064.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢