Emerg Med J doi:10.1136/emermed-2011-200868

Short answer question case series: controversies in the diagnosis and management of diverticulitis

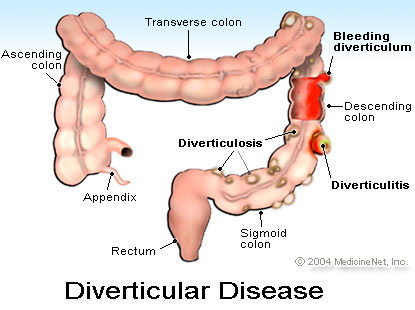

之前也有跟各位介紹過:憩室炎 Diverticulitis

Josh Beck, Timothy B Jang

Correspondence to Dr Timothy B Jang, Department of Emergency Medicine, Harbor UCLA Medical Center, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, 1000 W. Carson St., Torrance, CA 90509, USA; tbj@ucla.edu

[EXCERPTS]

Case vignette

A 50-year-old man with no medical history presents with 2 days of left lower quadrant pain. He describes the pain as ‘achy’ and says that it began gradually and has been progressively worsening. He has had one episode of non-bloody diarrhoea but has not had any nausea or vomiting and denies any urinary symptoms. On examination, he is found to be afebrile with normal vitals signs and has only mild left lower quadrant pain.

Key questions

- What is the differential diagnosis for this patient?

- How should this patient be evaluated?

- How should this patient be treated?

- What is the appropriate disposition for this patient?

Discussion

- Since the patient has left lower quadrant pain of subacute onset, the differential diagnosis should include diverticulitis, renal colic or testicular pathology. Also on the differential diagnosis, although less likely, would be prostatitis, pyelonephritis, atypical appendicitis and cancer.

- The patient should undergo a thorough physical examination including a testicular and prostate examination. Laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, chemistry and urinalysis.

The availability of CT has led to the replacement of x-rays as the preferred imaging method in most groups. In women of childbearing age, however, ultrasound is the recommended study due to the risk of radiation and the high likelihood of a pelvic aetiology of left lower quadrant pain.

The more difficult question perhaps is when to employ the appropriate diagnostic test. Diverticulitis has classically been considered a disease that affects older people and due to the higher risk of morbidity and mortality, it was the standard of care to image them. However, the increased use of CT scanning has led to a shift in the epidemiology of disease diagnosis with younger patients making up a substantial portion. While they would seem to comprise a low risk group in which imaging would not be necessary, some evidence has suggested that those <40 years of age are actually at higher risk of complications from simple diverticulitis.

The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) guidelines specifically state ‘The diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is based on clinical findings and leukocytosis…CT scanning is usually reserved for patients with suspected abscesses or perforations, those who fail to respond to medical therapy, or in whom the diagnosis is not clear.’ This is consistent with the guidelines published by the National Health Service of England. On the other hand, while the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' (ASCRS) guidelines generally concur with the appropriateness of a clinical diagnosis, they note that initial CT findings can be highly predictive of morbidity and outcomes in diverticulitis and may be clinically relevant. Unfortunately, no study has isolated CT findings from other factors like fever, leukocytosis or focal pain, so it is impossible to determine whether specific clinical factors would distinguish patients at increased risk of morbidity from those with the classic presentation of uncomplicated diverticulitis. Thus, it seems reasonable, based on the evidence as a whole, to image all patients with suspected diverticulitis who are over 65 years or under 40 years regardless of fever or leukocytosis. In patients between 40 and 65 years, a CT scan only needs to be obtained in the presence of high fever, immune compromise status, failure of outpatient management or other high-risk features such as bleeding or peritonitis.

- As is the case with imaging, there are no consensus guidelines for the antibiotic management of these patients. The NHS recommends augmentin as the preferred therapy with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole as an alternative for those with penicillin allergy. Many options have demonstrated efficacy, including the combinations of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and metronidazole, a fluoroquinolone and metronidazole or clindamycin and gentamicin, plus single coverage regimens with cefoxitin, piperacillin–tazobactam or ampicillin–sulbactam.

- ASCRS defines ‘uncomplicated diverticulitis’ as ‘diverticulitis without abscess, fistula, obstruction, or perforation’. Their guidelines allow for the outpatient treatment of those without ‘appreciable fever, excessive vomiting, or marked peritonitis’. The NHS adds the recommendation to admit patients who are ‘very elderly’ or those with ‘immunosuppression’ with consideration for admission of those <40 years. The evidence for admitting the ‘very elderly’ and ‘immunosuppressed’ is quite clear and intuitive. The reason for admitting those <40 years is due to their increased risk for surgical complications with a RR of urgent surgery three to four times greater than the 40–65 years age group. In cases of perforated diverticulitis, patients should be admitted to a surgical service. In cases of diverticulitis with abscess formation, admission is still required but inpatient management may range from intravenous antibiotics and percutaneous drainage to surgical management.

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢