Tourette’s syndrome

你也可以參考這一篇:比較妥瑞症與亨丁頓與舞蹈症

妥瑞氏症是一種遺傳性的神經運動疾病。

1825年,一位法國神經科醫生Jean-Marc Itard 首度將妥瑞氏症描述下來,當時Itard正在照顧一位從7 歲開始發展出聲語型抽筋的貴婦。由於抽筋使她無法控制的發出尖叫聲和咒罵聲,因此她被送往隔離。 在Itard 首度紀錄妥瑞氏症的六十年後,神經心理學家Edouard Brutus Gilles de la Tourette (出生於 1857; 死於 1904) ,於 1885 年詳盡的紀錄許多抽筋病患的病徵。 其中也包括Itard所研究的法國貴婦。

在美國約有10-20萬人罹患此疾病。大約有1百萬名美國人可能有非常輕微的 妥瑞氏症症狀。妥瑞氏症患者的身體會出現不自主的、重複性的動作,稱為抽筋(tics)。抽筋不會一直出現,但可能會因疲勞或壓力而惡化。

Andrea E Cavanna and Stefano Seri

Correspondence to: A E Cavanna, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Barberry National Centre for Mental Health, Birmingham B15 2FG, UKa.cavanna@ion.ucl.ac.uk

[EXCERPTS]

Summary points

- Tourette’s syndrome is a tic disorder that is often associated with behavioral symptoms

- Diagnostic criteria are based on the presence of both motor and vocal tics; because of its varied presentations, the syndrome has the potential to be misdiagnosed

- Prevalence is higher than commonly assumed; coprolalia is relatively rare (10-30%) and not required for diagnosis

- The syndrome can cause serious distress and compromise health related quality of life

- The main management strategies include psychoeducation, behavioral techniques, and drugs

- Service provision is patchy even in developed countries and patients of all ages often “fall through the net” between neurology and psychiatry

Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome, or Tourette’s syndrome, is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by multiple motor and vocal tics, which appear in childhood and are often accompanied by behavioral symptoms. Originally described by French physician Georges Gilles de la Tourette in 1885, this syndrome has long been considered a rare medical condition, until large epidemiological studies showed that 0.3-1% of school age children fulfil established diagnostic criteria for this condition. In the United Kingdom, it is estimated that as many as 200 000-330 000 people are affected, with different degrees of severity. Although it is estimated that about two thirds of patients with GTS improve by adulthood the syndrome affects health related quality of life. This article reviews current knowledge about the diagnosis and management of Tourette’s syndrome, including drug treatments and behavioral interventions.

What is Tourette’s syndrome and who gets it?

The chronic presence of at least two motor tics and one vocal tic since childhood is recognized as the key feature of Tourette’s syndrome. Tics are defined as involuntary, sudden, rapid, recurrent, non-rhythmic movements (motor tics) and vocalizations (vocal or phonic tics). It is now known that the syndrome occurs worldwide, across all races and ethnicities, in both sexes (four times more prevalent in males than in females), and in children as well as in adults, although the average age at onset is around 6 years and adult onset of tics is rare.

Motor tics generally precede the development of vocal tics, and the onset of simple tics often predates that of complex tics. Simple motor tics can manifest themselves as eye blinking, facial grimacing, shoulder shrugging, neck stretching, and abdominal contractions. The most common vocal tics are sniffing, grunting, and throat clearing. Gilles de la Tourette’s original case series described nine patients who also presented with complex tics; namely, echolalia (repeating other people’s words) and coprolalia (swearing as a tic). Both coprolalia and copropraxia (involuntary production of rude gestures as complex tics) are relatively rare, occurring in about 10% of patients (20-30% in specialist clinics where more severe or complex cases are seen).

Both simple and complex tics are characteristically preceded by a feeling of mounting inner tension, which is temporarily relieved by tic expression. These sensations, also known as “premonitory urges,” are a hallmark feature of tics, and they enable clinicians to reliably distinguish Tourette’s syndrome from other hyperkinetic movement disorders. However, unequivocal reports of these sensations can prove difficult to elicit in younger children.

How is Tourette's syndrome diagnosed?

The diagnosis is clinical and relies on skilful observation and comprehensive history taking. Updated diagnostic criteria for tic disorders, including Tourette’s syndrome, have recently been published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (box). The complex symptoms that were originally described by Gilles de la Tourette (such as coprolalia and echolalia) are not included in the diagnostic criteria, which do not distinguish between simple and complex tics. The differential diagnosis of tics includes myoclonic jerks, mannerisms, and stereotypies (especially in the context of autistic spectrum disorders), in addition to other hyperkinetic movement disorders with onset in childhood. Specific investigations, including laboratory tests and neuroimaging, are indicated only to rule out other possible causes of tics in patients with atypical presentations, which include acute onset, onset in adulthood, or sustained/dystonic tics.

Current diagnostic criteria for Tourette’s syndrome

- At least two motor and one vocal tic (not necessarily concurrently)

- Presence of tics for at least 12 months

- Onset before age 18 years

- Tics not caused by the physiological effects of substances (such as stimulants) or other medical conditions (such as Huntington’s disease)

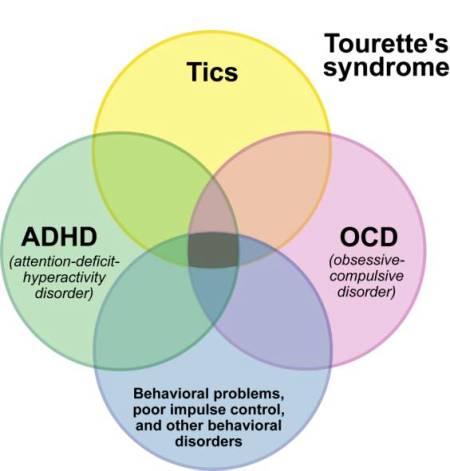

Does Tourette’s syndrome occur with other disorders?

Most patients with Tourette’s syndrome also have specific behavioral symptoms, which can complicate the clinical picture considerably. Converging evidence from large clinical studies conducted in specialist clinics, and in the community, indicates that only 10% of patients have no associated psychiatric comorbidity (pure Tourette’s syndrome). Consequently, the behavioral spectrum of the condition is multifaceted (figure) and the management of patients with “Tourette’s syndrome plus” can pose considerable challenges even to experienced clinicians. Obsessive-compulsive disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are the most common comorbidities, with an estimated prevalence of around 60%. Interestingly, the obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms associated with tics overlap only partially with the clinical presentation of patients with primary obsessive-compulsive disorder. For instance, patients with Tourette’s syndrome report a significantly higher prevalence of concerns about symmetry, “evening-up” behaviors, obsessional counting (arithmomania), and “just right” perceptions, whereas patients with pure obsessive-compulsive disorder have a higher rate of cleaning rituals, compulsive washing, and fears of contamination. These differences probably result from different pathophysiological mechanisms, because only certain obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms are considered intrinsic to Tourette’s syndrome. Similarly, some complex tics can be misdiagnosed as compulsions, possibly leading to overdiagnosis of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder, as it seems to be suggested by the results of recent epidemiological studies.

Schematic representation of the behavioral spectrum in Tourette’s syndrome: the size of each area is proportional to the estimated prevalence of the symptoms; the background colour intensity is proportional to the complexity of the clinical presentation

What causes Tourette’s syndrome?

Little is known about the exact brain mechanisms associated with tic development and expression, although preliminary evidence from neurochemical and neuroimaging investigations suggests a primary role for dysfunction of the dopaminergic pathways within the cortico-striato-cortico-frontal circuitry. Neuropathological studies of patients with Tourette’s syndrome are rare, but a few studies have provided evidence for deficits in cerebral maturation, in particular at the level of striatal interneurone migration. Genetic predisposition has a major role in the development of the syndrome, as shown by early family studies. Although segregation analyses of large kindreds with multiple affected generations initially suggested an autosomal dominant transmission model, polygenic and bilineal transmission were also postulated, and subsequent investigations found that the syndrome is a genetically heterogeneous disorder.

Findings from epidemiological and laboratory studies have also drawn attention to the role of environmental factors, including infections and autoimmune dysfunction, as well as prenatal and perinatal problems, in at least a subset of patients. The hypothesis that Tourette’s syndrome can be subsumed in a group of conditions called pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections is still controversial and requires further investigations. The concepts of genetic and aetiological heterogeneity are in line with recent clinical phenomenology studies, which confirmed the existence of multiple phenotypes within the disease spectrum by using principal component factor analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis.

Whom should I refer to a specialist?

Patients with suspected Tourette’s syndrome should be referred to a specialist clinic, often part of a wider neuropsychiatric service, where multidisciplinary input can be provided. Because such clinics are few and far between, GPs can initially refer younger patients to local child and adolescent mental health services or community pediatrics services for a general neurodevelopmental and behavioral assessment. Specialist clinics could then be involved if the diagnosis is uncertain (for example, when comorbidities are present) or to deliver specific treatments. In adults, the pathway would be from primary care to adult neurology or neuropsychiatry. Once the diagnosis is established, patients should be reviewed at least once a year by a clinician with knowledge about the complexities of the disorder and its evolving treatment. Specialist services for these patients are in great demand because this fascinating area of neuropsychiatric medicine is underdeveloped in the UK.

What behavioral treatments are available?

A wide range of behavioral interventions have been developed or adapted to help patients maximize tic control. Habit reversal training or exposure and response prevention seem to be the most promising approaches. These methods aim to enable patients to recognize premonitory urges and modify the response to their occurrence, so that tic expression is delayed and eventually abolished. Recently, two large randomized controlled trials in children and adolescents and adults with Tourette’s syndrome or chronic tic disorders found that a comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics that incorporated habit reversal training significantly reduced tic severity in about half of the patients. Motivation to engage in the therapy sessions and full awareness of the premonitory urge are important factors that can increase response rate. In addition to enhancing tic suppression, psychological interventions can improve patients’ awareness of the environmental factors that affect their tic severity and can provide valuable support and skills to deal with tic associated behavioral symptoms. Access to behavioral treatment is currently limited even in developed countries. In the future, telemedicine or remote consultations might widen access to specialist diagnostic and therapy services.

Which drugs are effective?

Few double blind randomized controlled trials have been conducted to test the efficacy of drugs for tic management, especially newer ones, for which recommendations are based on case series and open label trials. The first drugs to show effectiveness in tic control were neuroleptics, especially haloperidol and pimozide. These are still considered among the most effective tic suppressants, and in many countries they are the only drugs licensed for Tourette’s syndrome, based on multiple randomized controlled trials. However, their poor tolerability profile, mainly due to extrapyramidal and metabolic side effects, restricts their use to second line or third line options, and only in selected patients.

Over the past couple of decades these drugs have been replaced by the newer antidopaminergic agents—the atypical antipsychotics—which are better tolerated overall and have similar efficacy for tic control. Within this group, there are positive data from randomized controlled studies for risperidone and promising findings from open label studies for aripiprazole, which has the best tolerability profile thanks to its partial dopamine agonist action. Aripiprazole has led to tic reduction in 65-85% of patients treated in open label trials, whereas rates of discontinuation due to adverse effects have been lower than 25%. Substitute benzamides (such as sulpiride) and presynaptic dopamine depletors (such as tetrabenazine) offer valuable alternatives, although both these drug classes and the newer antipsychotics can still have serious metabolic side effects, especially hyperprolactinaemia and weight gain. Importantly, antidopaminergic agents can also be useful as augmentation therapy in patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonergic agents because of severe comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Centrally acting α2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine and guanfacine, can be considered as first line treatment for young patients, because they have fewer adverse effects than other classes and their antinoradrenergic action can also be effective for comorbid ADHD. Evidence of efficacy against tics is also robust (randomized placebo controlled double blind trials), and mild side effects related to their hypotensive action should be monitored. Benzodiazepines should be avoided for the long term management of tics because of addiction and tolerance. However, positive results from open label and double blind controlled trials indicate that other agents that enhance γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity, particularly antiepileptic drugs such as topiramate, have shown some benefit in small open label and double blind controlled trials, although further studies are needed to confirm this. Likewise, preliminary evidence for tic suppressing properties from controlled trials on Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol should prompt further investigations on the efficacy and tolerability of purified cannabinoids, especially in adults who are refractory to treatment. Despite the paucity of evidence based data, the recently published European guidelines offer useful treatment algorithms based on the consensus of a large number of experts.

Is there any other treatment?

Botulinum toxin injections are indicated for the symptomatic treatment of isolated tics (including vocal tics), with positive results from open label studies, especially in patients with focal dystonic tics. Finally, a few selected patients with severe tics who do not respond to conventional interventions might be considered for surgery. The first patient with Tourette’s syndrome who successfully underwent the functional neurosurgical procedure of thalamic deep brain stimulation was reported in 1999. Since then, more than 100 procedures have been reported, mainly single case reports and small case series, with varying degrees of success. There is therefore little evidence on which surgeons can determine the suitability of a candidate and the optimal brain target because deep brain stimulation of the globus pallidus-pars interna and thalamic ventromedian-parafascicular nucleus often yield similar results in terms of efficacy, with the first option showing a better side effect profile. Currently, this procedure is still considered as a last resort and is rarely recommended.

Tips for non-specialists

- Tics are not just habits and should not be ignored if they cause distress

- Tics tend to run in families and can be motor or vocal-phonic

- Involuntary swearing is a socially disabling tic symptom that is present in only 10-30% of patients with Tourette’s syndrome

- The presence of comorbid behavioral symptoms often makes the diagnosis more difficult

- Multidisciplinary care within specialist settings is recommended when the clinical picture is unclear, complex, or challenging

- Offer psychoeducation and discuss behavioral and drug treatments with patients

- Refer patients to useful sources of information, such as the Tourettes Action or Tourette Syndrome Association’s websites

BMJ 2013;347:f4964

[Free full-text BMJ Clinical Review PDF | PubMed® abstract]

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢