之前也有跟各位提過:

ABSTRACT: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors are a class of drugs used to treat several common malignancies, including breast, colon, lung, and pancreatic cancer. Cutaneous adverse reactions have been reported to occur in approximately 90% of patients treated with an EGFR inhibitor. Skin rash from this class may decrease patient compliance, lead to discontinuation of therapy, affect quality of life, increase risk of infection, and reduce treatment effectiveness. Therapeutic intervention involves appropriate skin care, sun protection, moisturizers, topical corticosteroids, and topical or systemic antibiotics. Pharmacists can play an important role in the identification and appropriate treatment of EGFR inhibitor–related skin rash.

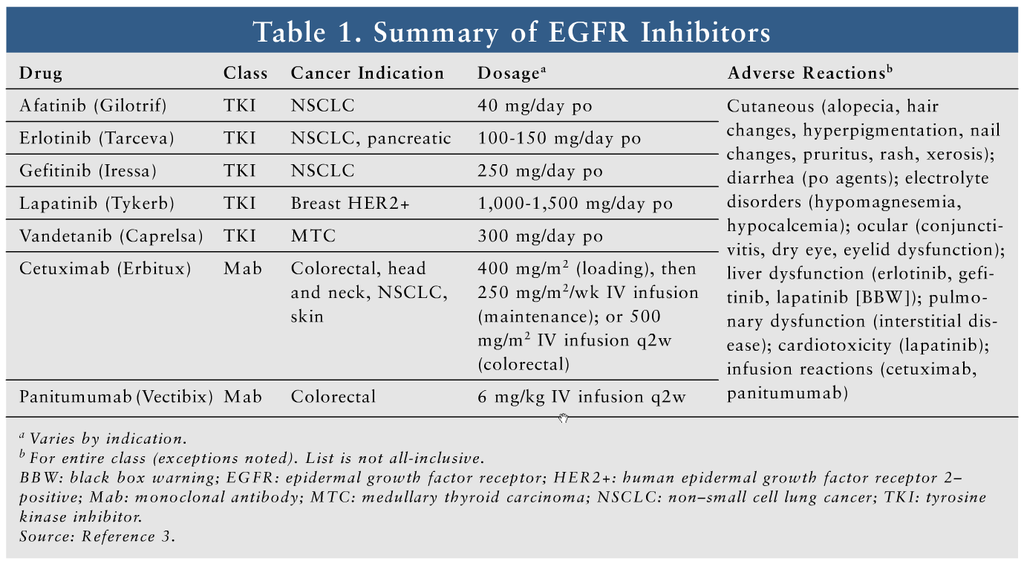

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a surface receptor widely distributed throughout many cell types, is overexpressed in many malignancies.1 Pharmacologic blockade of EGFR can inhibit tumor cell signaling and proliferation.2 EGFR inhibitors are widely used for cancers of the lung, pancreas, breast, colon, head and neck, and skin. This class consists of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; afatinib, erlotinib, gefitinib, lapatinib, and vandetanib) and monoclonal antibodies (Mabs; cetuximab and panitumumab). TKIs block tyrosine kinase activity, resulting in downstream disruption of the EGFR pathway. Mabs block binding to the EGFR, thus inhibiting phosphorylation and cellular activation.3 TABLE 1 summarizes cancer indications, dosages, and common adverse reactions (ARs) of EGFR inhibitors.3

Dermatologic reactions are the most common ARs associated with EGFR inhibitors, affecting up to 90% of patients.4-6 Skin toxicity associated with EGFR inhibitors is thought to be due to the high expression of EGFRs in the epidermis and the release of inflammatory cytokines by EGFR inhibitors. These dermatologic toxicities can affect the nails, hair, and skin and can manifest as dryness, brittleness, cracking, crusting, pruritus, and thinning.7,8 This article will focus on EGFR inhibitor–related skin rash.

Rash Characterization

The most common cutaneous toxicity is papulopustular rash, often mistakenly described as acneiform rash.4 This characteristic rash is most commonly seen in areas that have an abundant expression of sebaceous glands, such as the face, neck, chest, and back.7 The rash, which appears as erythematous papules and pustules, can cause marked pain, irritation, and pruritus. Dermatologic toxicity most commonly occurs within the first 1 to 3 weeks of treatment and peaks at 3 to 4 weeks. Patients usually experience a mild-to-moderate rash, with few experiencing a more severe rash. Complete resolution usually occurs within 3 months of drug discontinuation.4 However, patients may experience some degree of redness and hyperpigmentation even after the rash has resolved.7

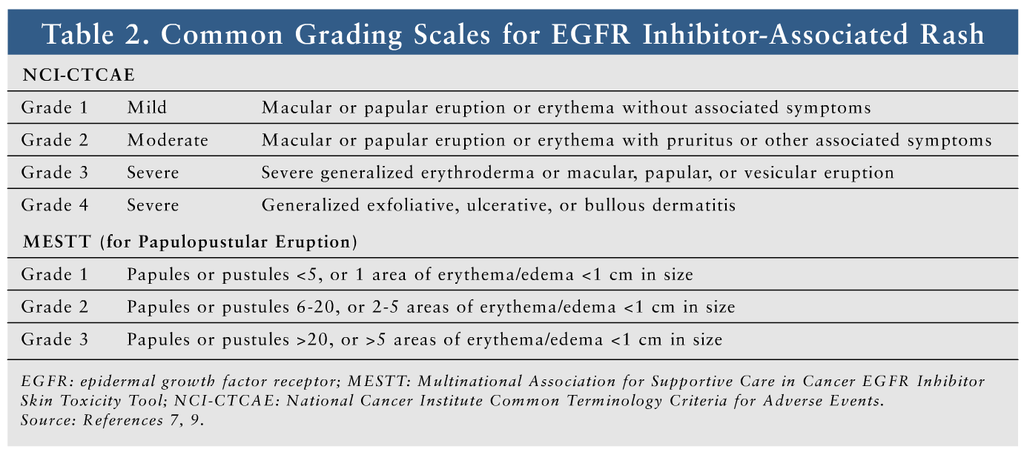

Several scales for grading these rashes are described in the literature. The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) is most commonly used, but it is not specific for EGFR inhibitor–induced rash.9 The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) has proposed that the MASCC EGFR Inhibitor Skin Toxicity Tool be used, since it is specific for EGFR inhibitor–associated rash.7 TABLE 2 lists the common grading scales.7-9

Since a variety of terminologies, definitions, and grading scales are used to characterize EGFR inhibitor–associated rash, it is difficult to quantify the exact incidence of rash for the different agents.10 Severe rash is more common with Mabs than with TKIs.11 Risk factors for dermatologic toxicities vary between agents; for example, nonsmokers, fair-skinned patients, and patients aged 70 years and older are at greater risk for developing a rash from erlotinib, whereas males and patients younger than 70 years are more likely to develop a rash from cetuximab.7

Evidence suggests that the skin reaction may act as an indicator of treatment response. Patients who develop skin reactions to cetuximab and erlotinib generally have a higher response to treatment and an increased survival rate.10,12-14 This positive correlation with outcome may offer patients dealing with rash some comfort and hope. Prevention and treatment recommendations are based on controlled clinical trials, when possible; however, many current recommendations are derived from expert opinion.

Treatment

Approximately one-third of patients with EGFR inhibitor–associated skin rash require therapeutic intervention.15 This article discusses overall treatment recommendations from the MASCC, as well as recommendations by grade from the British Columbia Cancer Agency’s rash protocol. Because of the lack of controlled trials in this setting, many recommendations are based on expert consensus.

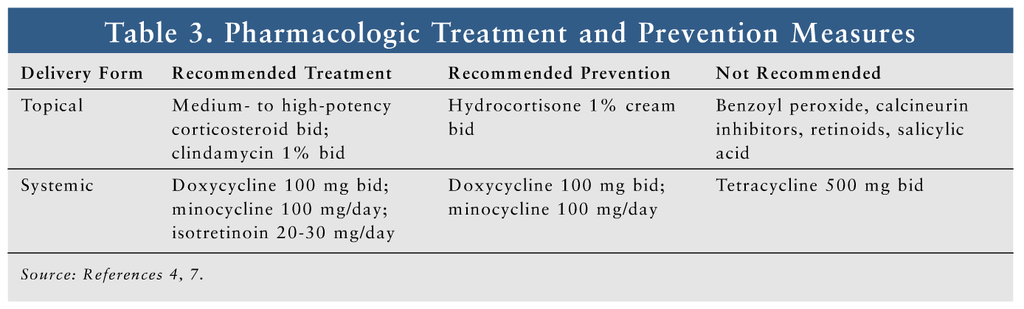

Pharmacologic options for treatment and prevention appear in TABLE 3. The MASCC treatment recommendations for papulopustular rash include the use of a medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroid and a systemic antibiotic.7 Medium- and high-potency topical corticosteroids, which are available by prescription only, include—but are not limited to—triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream, hydrocortisone valerate 0.2% ointment, fluticasone propionate 0.5% cream or lotion, mometasone furoate 0.1% cream, and fluocinonide 0.05% cream.16 The topical corticosteroid should be applied to the affected area twice daily. It is acceptable to use topical corticosteroids on the face in this setting, since skin thinning is not likely to occur with short-term use, but caution is required.10

Because EGFR inhibitor–induced skin rash commonly occurs on the face, patients should be warned about the increased risk of corticosteroid-associated ARs when topical corticosteroids are applied to the thin skin around the eyes for a prolonged period of time.17 The use of occlusive dressings is not recommended with topical corticosteroids because of the increased risk of systemic absorption, side effects, and secondary infection. The patient should be instructed to apply a thin layer to the skin (making sure that the skin is dry) and to use the medication for the shortest possible length of time.

There is currently a lack of data supporting the use of systemic corticosteroids for EGFR inhibitor–induced skin rash.10 Patients should avoid OTC acne medications like benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid, as these agents are not indicated for use and may increase dryness and irritation. Systemic treatment with minocycline 100 mg once daily or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily is recommended.7 Recent doxycycline shortages may render minocycline a more available option. Doxycycline is safer than minocycline in patients with renal impairment, but it causes more photosensitivity.3 Low-dose isotretinoin (20-30 mg/day) should be considered only when first-line agents have failed.7 Topical retinoids should be avoided, however, owing to their skin-drying effects.10

Another treatment strategy is based on rash severity. For mild rash, recommendations include topical clindamycin 1% plus a topical corticosteroid applied twice daily to affected areas until resolution of rash. For moderate and severe rashes, the topical treatments used for mild rash plus doxycycline or minocycline are recommended. Severe rash that is considered intolerable may warrant EGFR inhibitor dose reduction or discontinuation.4 Patients wishing to cover the rash with makeup should be advised that while this should not worsen the rash, the makeup should be removed with a hypoallergenic wash.10 Recent observational studies with vitamin K cream have demonstrated clinical improvement.18-20 Results of ongoing clinical trials with vitamin K cream may reveal more guidance on its place in therapy.

Several options exist for symptomatic relief from pain, inflammation, itching, and burning. Conventional analgesia options like acetaminophen and ibuprofen may be offered to patients complaining of a painful rash.10 Itching may be relieved with an oatmeal bath, an oral antihistamine, cold compresses, refrigerated lotions, or the local anesthetic pramoxine.4,7 Local anesthetics such as benzocaine should be avoided because of sensitivity reactions, and lidocaine should be avoided owing to systemic toxicity associated with excessive use.7

Overall, ARs with EGFR inhibitors are minimal compared with those of many conventional oncology agents.4 EGFR inhibitors are a highly effective treatment, so it is important to consider measures that will increase tolerability and prevent discontinuation. Despite this, a survey of U.S. oncologists noted a discontinuation rate of 72% in patients experiencing severe cutaneous toxicities related to EGFR inhibitors.21 Prior to EGFR inhibitor initiation, patients should be counseled on the possibility of cutaneous reactions and how they may affect quality of life. Pharmacists can educate patients regarding appropriate prevention and treatment options. These agents have the potential for various drug-drug interactions, so the pharmacist must be mindful of concurrent medications and potential interactions. Pharmacists can also recommend appropriate products for the rash, including topical corticosteroids, sunscreen, and emollients, and advise against products that may worsen the rash.

Prevention

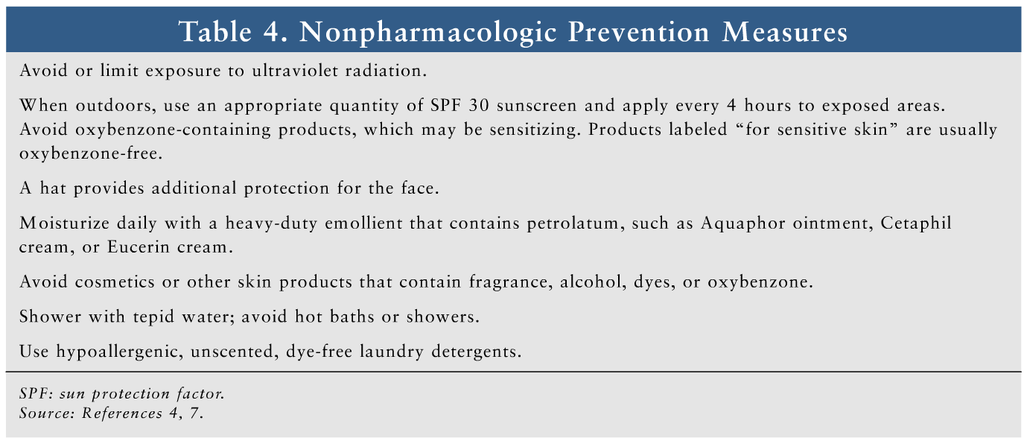

A variety of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic prophylactic measures are effective for reducing the severity of cutaneous reactions. Nonpharmacologic options for rash prevention are given in TABLE 4. The MASCCguidelines recommend prophylactic management consisting of hydrocortisone 1% cream, a moisturizer, and sunscreen applied to the face and upper body twice daily and a systemic antibiotic for the first 6 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy. Systemic prophylactic antibiotic management consists of either doxycycline 100 mg twice daily or minocycline 100 mg daily.7 Several agents are not recommended, including systemic tetracycline, tazarotene (Tazorac), topical retinoids, and topical calcineurin inhibitors like pimecrolimus (Elidel) and tacrolimus (Protopic).7,22,23 Pimecrolimus has failed to confer a benefit in patient-assessed rash severity, and it has a black box warning for potential cancer risk.24,25 Tazarotene did not demonstrate clinical benefit in a study of patients receiving cetuximab, and it may increase skin irritation.26

Conclusion

EGFR inhibitor–associated dermatologic toxicities are very common, and options are available for prevention and treatment. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic prevention measures should be considered whenever possible. Current therapies reduce the severity of the rash and may allow patients to continue EGFR inhibitor treatment. Pharmacists can play an important role in the management of EGFR inhibitor–induced skin rash by educating patients and healthcare providers on available prevention and treatment options.

REFERENCES

1. Rowinsky EK. The erbB family: targets for therapeutic development against cancer and therapeutic strategies using monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:433-457.

2. Harari PM. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition strategies in oncology. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:689-708.

3. Lexi-Comp Online. Afatinib; cetuximab; erlotinib; gefitinib; lapatinib; panitumumab; vandetanib. http://online.lexi.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed August 4, 2013.

4. Melosky B, Burkes R, Rayson D, et al. Management of skin rash during EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies: Canadian recommendations. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:16-26.

5. Ocvirk J, Heeger S, McCloud P, Hofheinz RD. A review of the treatment options for skin rash induced by EGFR-targeted therapies: evidence from randomized clinical trials and a meta-analysis. Radiol Oncol. 2013;47:166-175.

6. Sipples R. Common side effects of anti-EGFR therapy: acneform rash. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2006;22(suppl 1):28-34.

7. Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079-1095.

8. Lacouture ME, Lai SE. The PRIDE (Papulopustules and/or paronychia, Regulatory abnormalities of hair growth, Itching, and Dryness due to Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors) syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:852-854.

9. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 3.0, DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS. http://ctep.cancer.gov. Accessed July 25, 2013.

10. Pérez-Soler R, Delord JP, Halpern A, et al. HER1/EGFR inhibitor-associated rash: future directions for management and investigation outcomes from the HER1/EGFR inhibitor rash management forum. Oncologist. 2005;10:345-356.

11. Abdullah SE, Haigentz M, Piperdi B. Dermatologic toxicities from monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors against EGFR: pathophysiology and management. Chemother Res Pract. 2012;2012:351210.

12. Clark GM, Pérez-Soler R, Siu L, et al. Rash severity is predictive of increased survival with erlotinib HCl. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:196. Abstract 786.

13. Saltz L, Kies M, Abbruzzese JL, et al. The presence and intensity of the cetuximab-induced acne-like rash predicts increased survival in studies across multiple malignancies. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:204.

14. Saltz L, Hochster H, Tchekmeydian NS, et al. Acne-like rash predicts response in patients treated with cetuximab (IMC-C225) plus irinotecan (CPT-11) in CPT-11-refractory colorectal cancer (CRC) that expresses epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Proc NCI-AACR-EORTC. 2001;559.

15. Pérez-Soler R, Van Cutsem E. Clinical research of EGFR inhibitors and related dermatologic toxicities. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(11 suppl 5):10-16.

16. Ference JD, Last AR. Choosing topical corticosteroids. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:135-140.

17. Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, Cork MJ. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1-15.

18. Ocvirk J, Rebersek M, Boc M, et al. Prophylactic use of K1 cream for reducing skin toxicity during cetuximab treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl). Abstract e14011.

19. Pérez-Soler R, Zou Y, Li T, et al. Topical vitamin K3 (Vit K3, Menadione) prevents erlotinib and cetuximab-induced EGFR inhibition in the skin. J Clin Oncol (meeting abstracts). 2006;24(suppl 3036).

20. Radovics N, Kornek G, Thalhammer F, et al. Analysis of the effects of vitamin K1 cream on cetuximab-induced acne-like rash. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl). Abstract e19671.

21. Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, et al. Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology. 2007;72:152-159.

22. Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA, et al. Tetracycline to prevent epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced skin rashes: results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N03CB). Cancer. 2008;113:847-853.

23. Jatoi A, Dakhil SR, Sloan JA, et al. Prophylactic tetracycline does not diminish the severity of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor-induced rash: results from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (Supplementary N03CB). Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1601-1607.

24. Scope A, Lieb JA, Dusza SW, et al. A prospective randomized trial of topical pimecrolimus for cetuximab-associated acnelike eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:614-620.

25. FDA. Public Health Advisory: Elidel (pimecrolimus) Cream and Protopic (tacrolimus) Ointment. March 10, 2005. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm051760.htm. Accessed December 3, 2013.

26. Scope A, Agero AL, Dusza SW, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of prophylactic oral minocycline and topical tazarotene for cetuximab-associated acne-like eruption. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5390-5396.

- See more at: http://www.uspharmacist.com/content/s/288/c/46134/#sthash.ievyY6eF.ztd5bljY.dpuf

留言列表

留言列表

線上藥物查詢

線上藥物查詢